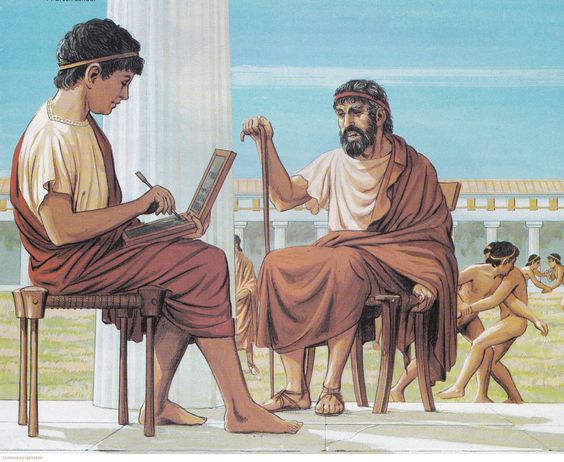

THE EDUCATION OF CHILDREN

BY PLUTARCH

The Education of Children Περὶ παίδων ἀγωγῆς by the Boiotian Greek historian and philosopher Plutarch Πλούταρχος of Chaironeia (ca. AD 46-120) who won Roman imperial favour and rose to become procurator of Achaia, was the first of the many essays in his Moralia, written around ca. AD 100. The translation is by Frank Cole Babbitt in Moralia, Volume I, the Loeb Classical Library Volume 197 published by William Heinemann in London in 1927. His romanisations of Greek names have been replaced by transliterations of the Greek.

Moralia 11d-12a

|

So far I have felt no doubt or even hesitation in saying what I have said about the decorous conduct and modest behaviour of the young; but in regard to the topic now to be introduced I am of two opinions and two minds, and I incline now this way, now that, as though on a balance, being unable to settle down on either side; and a feeling of great reluctance possesses me, whether to introduce or to avoid the subject. Still I must venture to speak of it. What is it then? It is the question whether boys’ lovers[1] are to be permitted to associate with them and pass their time with them, or whether, on the contrary, they should be kept away and driven off from associations with the youth. For when I have regard to those uncompromising fathers, harsh and surly in their manner, who think the society of lovers[2] an intolerable outrage to their sons, I feel cautious about standing as its sponsor and advocate. But again, when I think of Sokrates, Plato, Xenophon, Aischines, Kebes,[3] and that whole band of men who sanctioned affection between males,[4] and thus guided the youth onward to learning, leadership, and virtuous conduct, I am of a different mind again, and am inclined to emulate their example. Euripides[5] gives testimony in their favour when he says:

Nor may we omit the remark of Plato[6] wherein jest and seriousness are combined. For he says that those who have acquitted themselves nobly ought to have the right to kiss any fair one they please. Now we ought indeed to drive away those whose desire is for mere outward beauty, but to admit without reserve those who are lovers of the soul. And while the sort of love prevailing at Thebes and in Elis is to be avoided, as well as the so‑called kidnapping in Crete, that which is found at Athens and in Lakedaimon is to be emulated.[7] In this matter each man may be allowed such opinion as accords with his own convinces. |

[11d] Ταῦτα μὲν οὖν οὐκ ἐνδοιάσας οὐδὲ μελλήσας περὶ τῆς τῶν παίδων εὐκοσμίας καὶ σωφροσύνης διείλεγμαι· περὶ δὲ τοῦ ῥηθήσεσθαι μέλλοντος ἀμφίδοξός εἰμι καὶ διχογνώμων, καὶ τῇδε κἀκεῖσε μετακλίνων ὡς ἐπὶ πλάστιγγος πρὸς οὐδέτερον ῥέψαι δύναμαι, πολὺς δ᾿ ὄκνος ἔχει με καὶ τῆς εἰσηγήσεως καὶ τῆς ἀποτροπῆς τοῦ πράγματος. ἀποτολμητέον δ᾿ οὖν ὅμως εἰπεῖν αὐτό. [e] τί οὖν τοῦτ᾿ ἐστί; πότερα δεῖ τοὺς ἐρῶντας τῶν παίδων ἐᾶν τούτοις συνεῖναι καὶ συνδιατρίβειν, ἢ τοὐναντίον εἴργειν αὐτοὺς καὶ ἀποσοβεῖν τῆς πρὸς τούτους ὁμιλίας προσῆκεν; ὅταν μὲν γὰρ ἀποβλέψω πρὸς τοὺς πατέρας τοὺς αὐθεκάστους καὶ τὸν τρόπον ὀμφακίας καὶ στρυφνούς, οἳ τῶν τέκνων ὕβριν οὐκ ἀνεκτὴν τὴν τῶν ἐρώντων ὁμιλίαν ἡγοῦνται, εὐλαβοῦμαι ταύτης εἰσηγητὴς γενέσθαι καὶ σύμαβουλος. ὅταν δ᾿ αὖ πάλιν ἐνθυμηθῶ τὸν Σωκράτη τὸν Πλάτωνα τὸν Ξενοφῶντα τὸν Αἰσχίνην τὸν Κέβητα, τὸν πάντα χορὸν ἐκείνων τῶν ἀνδρῶν οἳ τοὺς ἄρρενας ἐδοκίμασαν ἔρωτας καὶ τὰ μειράκια προήγαγον ἐπί τε παιδείαν καὶ δημαγωγίαν καὶ τὴν ἀρετὴν τῶν τρόπων, πάλιν ἕτερος γίγνομαι [f] καὶ κάμπτομαι πρὸς τὸν ἐκείνων τῶν ἀνδρῶν ζῆλον. μαρτυρεῖ δὲ τούτοις Εὐριπίδης οὕτω λέγων ἀλλ᾿ ἔστι δή τις ἄλλος ἐν βροτοῖς ἔρως, τὸ δὲ τοῦ Πλάτωνος σπουδῇ καὶ χαριεντισμῷ μεμιγμένον οὐ παραλειπτέον. ἐξεῖναι γάρ φησι δεῖν τοῖς ἀριστεύσασιν ὃν ἂν βούλωνται τῶν καλῶν φιλῆσαι. τοὺς μὲν οὖν τῆς ὥρας ἐπιθυμοῦντας ἀπελαύνειν προσῆκε, τοὺς δὲ τῆς ψυχῆς ἐραστὰς ἐγκρίνειν κατὰ τὸ σύνολον. καὶ τοὺς μὲν Θήβησι καὶ τοὺς ἐν Ἤλιδι φευκτέον ἔρωτας καὶ τὸν ἐν Κρήτῃ καλούμενον ἁρπαγμόν, [12a] τοὺς δ᾿ Ἀθήνησι καὶ τοὺς ἐν Λακεδαίμονι ζηλωτέον. Περὶ μὲν οὖν τούτων, ὅπως ἕκαστος αὐτὸς ἑαυτὸν πέπεικεν, οὕτως ὑπολαμβανέτω· |

[1] The hopelessly weak and euphemistic “admirers” has been replaced by “lovers” as a translation of ἐρῶντας.

[2] The hopelessly weak and euphemistic “admirers” has been replaced by “lovers” as a translation of ἐρώντων.

[3] The first four of these five were Athenian philosophers and/or politicians of the classical period (480-323 BC) of sufficient fame for further elaboration to be excused. The last, Kebes, was a Theban, but like Plato and Xenophon, a disciple of Sokrates.

[4] The inexcusably inaccurate “men” has been replaced by “males” as a translation of ἄρρενας.

[5] In the Theseus; cf. Nauck, Trag. Graec. Frag., Euripides, No. 388. [Translator’s note]

[6] Republic 468b. [Translator’s note]

[7] The comparison of Thebes and Elis, where the sexual fulfilment of pederastic love affairs was easily accepted with Athens and Lakedaimon (better known to moderns as Sparta), where it was more complicated, echoes the speaker Pausanias in Plato’s Symposium: “Now here and in Sparta the rules about love are perplexing, but in most cities they are simple and easily intelligible; in Elis and Boiotia, and in countries having no gifts of eloquence, they are very straightforward; the law is simply in favour of these connexions, and no one, whether young or old, has anything to say to their discredit; the reason being, as I suppose, that they are men of few words in those parts, and therefore the lovers do not like the trouble of pleading their suit.” (Symposium 182a-b). Plutarch's confirmation of “the sort of love prevailing at Thebes” (the principal city of Boiotia), is valuable, since he was a Boiotian himself.

For the many ancient sources on Cretan pederasty, also sexually consummated without much complication, see the article Pederasty in ancient Crete.

Comments powered by CComment