KAROL SZYMANOWSKI, HIS BOY-LOVE NOVEL, AND THE BOY HE LOVED

BY HUBERT KENNEDY

The following biography of the Polish composer Karol Maciej Szymanowski (3 October 1882 – 29 March 1937) by American historical scholar and mathematician Hubert Kennedy was published in the journal Paidika (Amsterdam: Stichting Paidika Foundation) volume 3 (1994), no. 3 (issue 11), pp. 26–33.

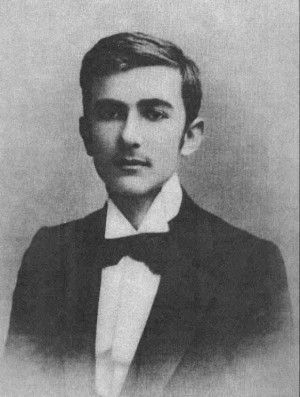

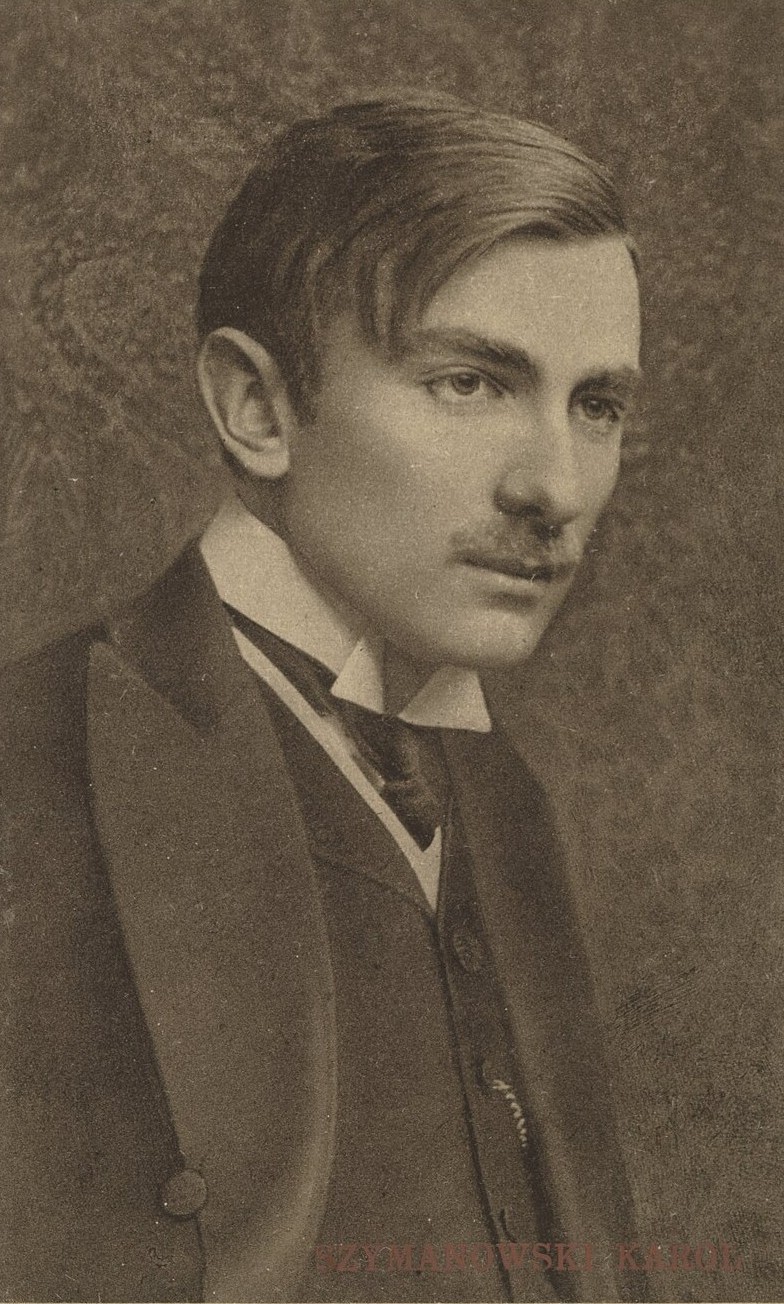

Karol Szymanowski (1882–1937) was one of the greatest Polish composers and a central figure in Polish music in the first half of the twentieth century. He left a large body of compositions in nearly every form, most of them marked by strong individuality.[1] He was also the author of numerous biographical and critical articles in several languages.[2]

That he was the author of a long novel on boy-love was not, however, generally known, until after his death, when his friend and literary executor, J. Iwaszkiewicz, allowed a brief passage to be read on Polish radio in March 1939. Although that short fragment was very discreet, it brought an angry letter from Szymanowski’s mother. It was probably the title of the novel, Ephebos, more than anything else, that caused eyebrows to rise. Then, in September 1939, at the beginning of the Second World War, the house in which the manuscript was kept was burned. Apart from the title page, drafts of a foreword, and a few small fragments, it was thought that the two-volume novel was lost forever. But, in 1981, the Polish musicologist Teresa Chylinska discovered in Paris a 150-page Russian version of the novel’s central chapter, “The Symposium,” in the collection of the aging Boris Kochno (1904–1990). It was a treasured souvenir of his youth; Szymanowski himself had made the translation as a gift, and had also presented Kochno with four poems in French.

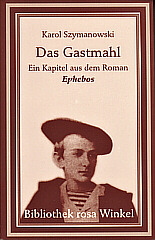

The original Polish of the chapter was painstakingly reconstructed, helped in part by the fact that Szymanowski’s Russian often used Polish grammatical constructions. This chapter, the poems, and a passage from Iwaszkiewicz’s memoirs describing the novel are now available in German translation.[3]

Karol Szymanowski was born on 6 October 1882[4] on the family estate Tymoszówka in the Ukraine. At age fourteen he was impressed by hearing Wagner for the first time, in Vienna. He studied music in Warsaw (1901–1904) and in the following decade made a reputation for himself by composing music in the German Romantic tradition of Wagner and, especially, Richard Strauss. Then his interest shifted, as described by the British musicologist Christopher Palmer:

The young composer’s interest in German musical culture began to decline steeply as a result of his travels with Stefan Spiess, first to Southern Italy and Sicily in April 1911, then to Sicily and North Africa in 1914…. It is possible that, like Gide before him, these journeys into exotic lands where forbidden fruit was freely to be had (especially by well-to-do foreigners) enabled him to realize the true direction of his sexual impulses, and that this affected in no small way the blossoming of his creative personality. Szymanowski made no overt declaration of his homosexuality in his music; King Roger is the only work in which any kind of homoerotic element is to be discerned, and this treatment of it is unsensational and unself-conscious. Rather is it his two-volume novel Ephebos, which is described by [Szymanowski’s biographer] Maciejewski as Szymanowski’s “apologia pro vita sua.”[5]

Szymanowski’s opera King Roger, set in medieval Sicily, was begun in 1918 and completed in 1924. As described by Chylinska, “The text, written jointly with Iwaszkiewicz, is based, broadly speaking, on the Dionysian thesis that only through bodily love can the mysteries of divine love be approached or creative work accomplished.”[6] At the conclusion of his description of the opera, Jim Samson wrote:

Here in these final pages, as Roger salutes Apollo in the rising sun, his vocal line achieves a dignity and strength which had formerly eluded it. His life has been enriched and transformed by the truths of Dionysus but he is no slave to them. He stands alone as a powerful symbol of modern Nietzschean man.[7]

Samson concludes, “In purely musical terms the opera has strong claims to be his masterpiece.”[8]

The middle period of Szymanowski’s musical development, a result of his visits to Sicily and North Africa, was his “period of greatest creative activity.”[9] There was to be a third, “nationalist,” period later, when he made much use of Polish folk music, but his middle, “impressionist” period was his most fertile.

Palmer describes the effects of Szymanowski’s southern travels on his music: “Szymanowski’s contact with oriental and classical antiquity engendered a species of spiritual and aesthetic awakening, a quickened perception, an urge to be made perfect by the love of visible beauty.”[10]

This “visible beauty” takes on more human form in the memoirs of Szymanowski’s longtime friend, the pianist Arthur Rubinstein, who wrote of meeting Szymanowski in Paris in 1921:

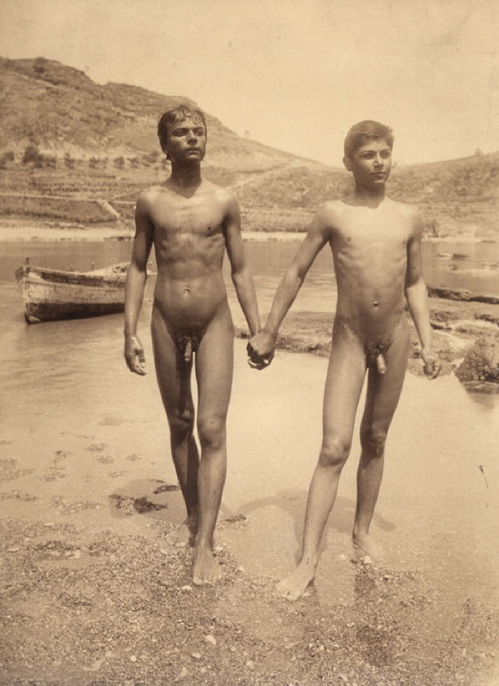

Karol arrived two days later in good physical shape after all he had been through…. Karol had changed; I had already begun to be aware of it before the war when a wealthy friend and admirer of his had invited him twice to visit Italy. After his return he raved about Sicily, especially Taormina. “There,” he said, “I saw a few young men bathing who could be models for Antinoüs. I couldn’t take my eyes off them.” Now he was a confirmed homosexual, he told me all this with burning eyes. “Paul [Kochanski] told you about all the terrible things which happened to us. I’m happy to tell you that I succeeded in bringing my whole family to Warsaw, where from now on I have to look after them. On several occasions we barely escaped with our lives. The peasants murdered a few landowners in the Ukraine and mutilated Prince Sanguszko, so we can thank God that we are all safe. But, Arthur, you won’t believe it, but in Kiev, right after the flight from Tymoszówka, I found the greatest happiness—I lived in heaven. I met a young man of the most extraordinary beauty, a poet with a voice that was music, and, Arthur, he loved me. It is only thanks to our love that I could write so much music. I even have a third sonata and a third symphony. Since my flight to Warsaw I lost all contact with him, so you can well imagine how I feel now.” I hardly recognized the Karol of old; here was a young man in love for the first time.[11]

The object of Szymanowski’s love was Boris Kochno, and there is no reason to doubt Rubinstein’s recollection of Szymanowski’s emotional state, but his chronology is faulty. It should be noted that Rubinstein dictated his memoirs at age 90, by memory and with no documentation. Here he has confused the sequence of events. Szymanowski met Kochno, not in Kiev, but two years later in the Ukrainian town of Elisavetgrad, which was near Tymoszówka.

Szymanowski was lame in his left knee as a result of several operations as a child, and so was not conscripted into the Czarist army during the First World War. Those years were musically very fertile for him, for he spent them in semi-isolation at Tymoszówka, devoting himself to composing. In addition to the works mentioned by Rubinstein there were, for example, Mythes, and Métopes, and, reflecting Szymanowski’s interest in Islamic culture, two collections of Love-songs of Hafiz, set to verses of the Persian poet, using the German translation of Hans Bethge.[12] As Chylinska wrote, “Almost all of the works written at this time share qualities of ecstasy and fervour, maintaining the utmost intensity of expression.”[13]

This intense period of composing came to an end, however, in 1917, when the manor house at Tymoszówka was destroyed during the Russian Revolution. Fortunately, the Szymanowski family was in Kiev at the time. In 1918 they moved to Elisavetgrad, where the family owned two houses.[14] In this grim period Szymanowski wrote Ephebos as a way of overcoming “days, weeks, and months of the most depressing circumstances” through “the magic of Italian scenes evoked from memory,” as he wrote in his foreword to the novel. Or, as Maciejewski expressed it: “Szymanowski escaped from reality, and wrote a novel Efebos [sic] about a beautiful Prince, beautiful Rome, beautiful love.”[15]

The novel gained added importance in the spring of 1919 with the arrival in Elisavetgrad of the fifteen-year-old Boris Kochno. Szymanowski fell in love with him, and apparently, as suggested by Rubinstein, the love was returned. A budding poet, Kochno’s burning passion was to experience the Ballets Russes in Paris. Szymanowski introduced him to Stravinsky’s ballet music, playing four-handed piano arrangements with Henryk Neuhaus, the son of Szymanowski’s music teacher. As Wolfgang Jöhling observed, “By his stay in Elisavetgrad, Boris profited richly for the development of his personality, and probably became clear here about his sexual orientation.”[16] In December 1919, Szymanowski was able to sell his property in Elisavetgrad, and the family moved to Warsaw, now the capital of a free and independent Poland. In 1920, Szymanowski’s “little boy” (Szymanowski used the English phrase in one of the French poems addressed to Kochno) traveled on to Paris with his mother, and Szymanowski lost touch with him. Richard Buckle, Diaghilev’s biographer, told how Kochno achieved his goal of meeting the impresario:

Boris and his mother reached Paris on 9 October 1920. Among his friends in exile were the painter Sudeikine and his wife Vera [who later married Stravinsky]. Sudeikine, of course, was an old acquaintance of Diaghilev. . . . To Sudeikine and Vera, Boris spoke continually about Diaghilev . . . whom it was his ambition to meet. While the handsome Kochno sat for his portrait, Sudeikine devised a little plot to satisfy his young friend. Kochno should go to Diaghilev’s hotel with a message from Sudeikine….

On 27 February 1921, a Sunday, Boris ... walked to the Hotel Continental…. He asked for Diaghilev. The clerk ... told him to go straight up. Diaghilev was expecting someone who never came…. [Diaghilev] showed no surprise that an unknown young man had called upon him…. When he left at one o’clock, Diaghilev escorted him to the door and said, “We shall meet again.”

Next morning, when Kochno returned to the Continental, Diaghilev asked him if he would like to be his secretary. The dream began.[17]

I met [Diaghilev] on February 27, 1921. He asked me my age (I was nearly seventeen)—and about my life in Russia (where he had not been since 1914). I recited my poems to him—in my youth I was a poet—and at the end of our conversation he engaged me as his secretary[18].

Three months later, Szymanowski, who had stopped in Paris on his return from his first trip to the United States, saw his beloved Boris once more. Rubinstein described the poignant occasion:

With the great help of Misia [Sert], who was of Polish origin, we tried to interest Diaghilev in Szymanowski and his music and we succeeded. Diaghilev invited Karol and me for dinner at the Continental.

We arrived punctually, asked the desk to telephone his room and announce our arrival, and sat down and waited in the lobby. After a few minutes we saw the great man appear at the top of the staircase to the second floor and come slowly down toward us, followed by a young man. Szymanowski, who had been waiting indifferently, looked suddenly as if he were about to have a heart attack. He scared me. But in less than a second I saw that his face was composed again, although there was a tragic expression in his eyes. Diaghilev greeted us graciously and introduced the young man as a new collaborator. Karol murmured something and we went to dinner. I suddenly knew what was wrong; when the young man came down the staircase I saw on Szymanowski’s face who he was, and the dinner became a game. Diaghilev showed that he had an inkling that something was in the air and the young man, mortally afraid of losing his position, had to play the extremely difficult rôle of someone who had never met Karol before. And Karol was torn between the wild urge to speak out and the knowledge that the young man would immediately be dismissed and that Diaghilev would have nothing more to do with Karol. I had to play the part of moderator and keep the conversation flowing. The arrival of Stravinsky saved the situation. He involved Diaghilev immediately in a long discussion about their plans, which allowed the other two actors of the drama to exchange a few short glances of recognition. Two or three furtive meetings were all Karol succeeded in arranging, but I think it was a sad end to their love.[19]

Apparently Diaghilev never learned that Kochno had known Szymanowski, for the new relationship continued. Kochno had asked what his duties as secretary were, and Diaghilev’s memorable reply was: “A secretary must know how to make himself indispensable.”[20] Kochno took the initiative and made himself indispensable. Diaghilev took other lovers later, but Kochno remained his friend until Diaghilev died in 1929. Buckle reported:

Boris was never paid, but Diaghilev lodged and fed him at the finest hotels in Europe, and dressed him at the best English tailors. He did not mind asking Diaghilev, from time to time, for a few francs to buy cigarettes. Kochno was not attracted by young men and he was prepared to love Diaghilev: but although he was handsome in a classical way, he was not Diaghilev’s type. As friends, however, they got on very well and remained inseparable.[21]

Kochno’s contributions to the Ballets Russes were considerable, especially his libretti for some of its most successful later ballets. Buckle, who called Kochno “the Shakespeare of the ballet scenario,”[22] reported that Diaghilev had begun to refer to Kochno as his successor, but due to internal dissension the company was dissolved after Diaghilev’s death. When the representative of the Monte Carlo theater asked Balanchine to form the Ballets de Monte Carlo in 1931, Kochno signed a contract as artistic director. But Balanchine was dismissed in 1932 and Kochno resigned. The following year the two formed Les Ballets 1933, whose name, as Buckle remarked, “hardly guaranteed longevity.” It did not last the year, and Kochno returned to life in Paris with his friend, the painter Christian Bérard. The two lay low during the Nazi occupation. After the war, in 1946, they founded the Ballets des Champs-Elysées, which Kochno directed until 1950.[23] Kochno also wrote a book about the Ballets Russes and assisted in several Diaghilev exhibitions, which always included items from Kochno’s own collection.

After the fateful meeting with Kochno in 1921, Szymanowski had returned to Warsaw, where his compositions assumed a more nationalistic style. He was director of the Warsaw Conservatory (1927–1932), but this did not stop his sexual interests. He wrote to his friend, the pianist Jan Smeterlin in 1929: “Forgive my type-written letter but a small portable Remington is a newly acquired eccentricity of mine (which does not mean that I have rid myself of my other eccentricities that you know so well, and which are less respectable!).[24]” Indeed, Smeterlin knew his “eccentricities”; a year later Smeterlin wrote from London:

Apparently the soldiers, those fine looking Horse-guards are no longer as free as they used to be. Poor chaps, the military police are very strict with them, but I rather think that this state of affairs will not last long.

In Paris, as always, I enjoyed myself very much. Once, I was forced to be of use as a Spanish interpreter in a bar in the rue de Lappe—you are aware of what sort of area that is?! A Spanish client was not able to understand a little French gigolo; then the Frenchman begged me to help him and when I had finally arranged for them both to sleep together, I demanded some payment for my services, but did not get any. I shall, therefore, continue to be a pianist, which is, after all, a slightly more honorable profession than that of a ‘Hotel tout’![25]

Szymanowski was in ill health in his last years, probably brought on by his smoking more than forty cigarettes a day. He died in Lausanne, Switzerland, on 29 March 1937. Rubinstein commented on the death of his “dearest friend”:

Karol was the only composer, after Chopin, who could represent Poland proudly all over the world and deserved all the help he needed from this mean government. When he was no more, the authorities trumpeted pompously the tragic loss of their great son. They prepared a Warsaw funeral with an unheard-of mass of publicity. A hundred thousand people were tightly massed to watch the funeral. A special train transported his body, accompanied by ministers and the family, to Cracow for the grand burial at the church at Skalla, where only the greatest of the nation were allowed to lie. They put on the catafalque the insignia of the Grand Cross of Polonia Restituta, the nation’s highest honor. What a bitter irony! For years they had made my poor Karol suffer through their meanness and now they were willing to spend a fortune on this big show. And what really infuriated me was the fact that they asked Hitler’s government to make the train with Karol’s body stop in Berlin long enough to receive military honors.[26]

In his foreword to Ephebos, Szymanowski challenged the public by avowing that his only concern was “to let the shining light of truth penetrate where only dark shadows and the poisonous viper-hissing of hate-sowing derision reigned.”[27] More than seventy years later, we smile at these words; the novel could hardly create the sensation today that Szymanowski expected of its publication. This can certainly be said of its central chapter, which is now available in German translation. But it is this chapter that Szymanowski prized the most: “In it I expressed much, perhaps all, that I have to say in this matter, which is for me very important and very beautiful.”[28]

There are six participants in Szymanowski’s “Symposium”:[29]

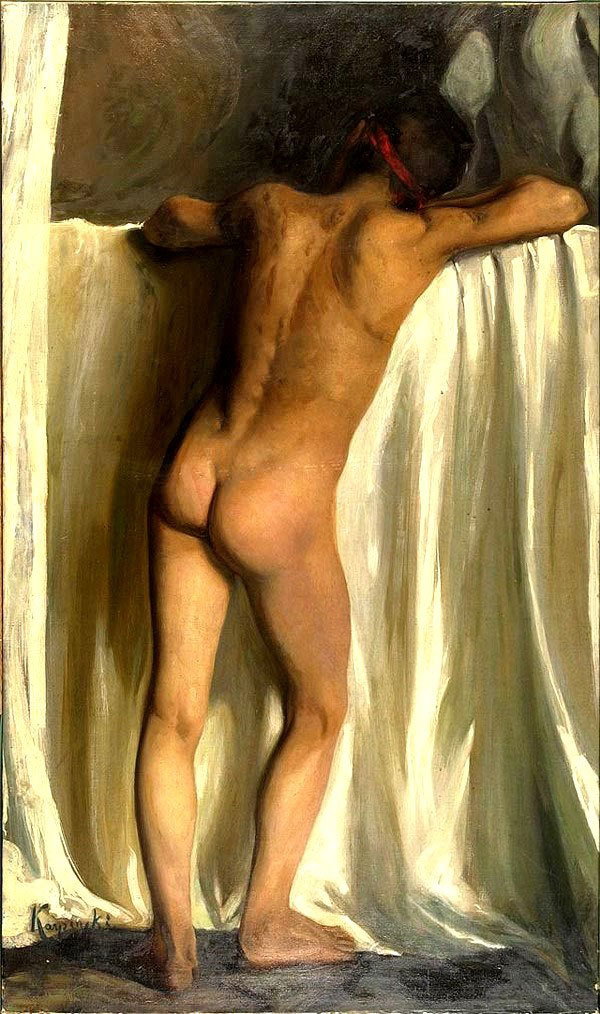

- Alo Lowicki, a Polish prince and the young hero of the novel, is an idealized portrait of Szymanowski as he had been. His age is suggested by the Greek title Ephebos; on the title page of his manuscript Szymanowski even wrote it in Greek letters.[30]

- Marek Korab, a Polish composer, is Szymanowski as he would like to be.

- The German Baron von Rellov first took Alo under his protection.

- The French Charles de Villiers is Alo’s bosom friend.

- Bissoli is an Italian professor and jurist.

- Y..., a German pianist, is perhaps based on Szymanowski’s friend, the pianist Henryk Neuhaus.

In the discussion, the last two defend conventional, heterosexual love; Rellov and Villiers advocate the cause of “true”, i.e., homosexual love. There is some preliminary sparring, in which de Villiers compares the body of a woman with that of a youth and finds the former wanting: her bosom breaks up the plane of belly and breast, her hips are too wide, etc., while Rellov trots out the standard list of great homosexuals of history: Socrates, Plato, Caesar, Cellini, da Vinci, Michaelangelo, Lorenzo de’ Medici, Shakespeare, and Charles XII (of Sweden). It is interesting to note that these were all manly individuals. Conspicuously absent, for example, is Henri III of France, who was briefly king of Poland (1574) and well known as an effeminate homosexual; Szymanowski would surely have known about him. It is unclear to what extent Szymanowski was acquainted with the available literature on the subject. All of these men had been discussed in the early 1900s in Berlin—in Magnus Hirschfeld’s Jahrbuch für sexuelle Zwischenstufen as well as in Adolf Brand’s journal Der Eigene. Szymanowski read German and had visited Berlin, and his views are closer to those often expressed in Der Eigene, rather than to the “third sex” views of Hirschfeld.[31]

In response to the argument that homosexual love is not natural, de Villiers argues that the “natural” is reduced to coitus and that from the beginning “true love” is “unnatural.” He addresses Bissoli:

Have you finally understood, learned professor? Have you grasped what true human love is? It is boundless in its freedom, the freedom of choice; it is based exclusively on the subjective and individual, psychic and physical characteristics of the human being. And no one and nothing, not even the so-called public, will dare to cut it off from the true, the good, and the beautiful, as perhaps old Socrates would have said.[32]

When Bissoli replies that “common sense” still holds same-sex love to be “abnormal,” de Villiers notes that, whereas common sense helped the cavemen, it is of little help now, when it serves only as a mask for “public opinion.”

Rellov then continues the argument that true love implies the freedom to choose: this comes first with liberation from the Law of Love in Nature, the sexual difference. In his view, there is no place here for woman, who is destined by nature to be (only) a mother. In addition to his anti-feminism, Rellov is also anti-Semitic: he finds the roots of our false culture in the Old Testament (which was taken over by the Germans through Luther). He contrasts it with the “true culture which grew from the pure Aryan root common to us all, somewhere at the foot of the Acropolis.”[33]

Alo is silently grateful for Rellov’s words, which he finds liberating. The evening’s discussion concludes only at the first light of dawn with the musings of Korab, and it ends on a mystical note when he tells of seeing a certain da Vinci portrait of Christ that allowed him to identify Christ with Eros:

I understood how, in the narrow circle of disciples and believers, simple, raw, and naive men, his words had been superficially and falsely interpreted. Only then did I grasp who He in reality was, He, Christ-Eros! ...

And he loved his neighbor with that mysterious, burning flame of his whole being, in the ardent wish for union with the everlasting creative essence of the world, which in supernatural light shines in the unfathomable eyes of the Lydian god with the ivy and rose crowned, copper-colored locks, with the blossom-clad Thyrsus staff in his hand.[34]

The Lydian god with the Thyrsus staff is, of course, Dionysus. Thus Jöhling notes that in this Symposium, “not only does Szymanowski develop a theory about the superiority of homoeroticism, on the basis of his own reflections on Plato and Nietzsche, but the dialogue also reflects his ‘private religion,’ the trinity of gods of love and life: Dionysus, Eros, and Christ—a view that in his opera King Roger is given an even clearer form musically and scenically.”[35]

Although one must take exception to the anti-feminism and anti-Semitism—which are discussed by Jöhling[36]—there is much that is valuable in Szymanowski’s Symposium, especially in his discussion of the natural. The emphasis on our freedom to choose in love is always welcome.

[1] For an excellent survey of the life and work of Szymanowski, see Teresa Chylinska, “Karol Szymanowski,” The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie (London: Macmillan, 1980), 18: 499-504. For an authoritative study of Szymanowski’s music, see Jim Samson, The Music of Szymanowski (London: Kahn & Averill, 1981).

[2] For example: “Frédéric Chopin et la musique polonaise moderne” (1931) and Wychowawcza rolakultury muzycznej w spoleczenstwie (The educational role of musical culture in society) (1931). Jim Samson reported that Alistair Wightman was preparing an English translation of Szymanowski’s articles (op. cit., p. 9).

[3] Karol Szymanowski, Das Gastmahl: Ein Kapitel aus dem Roman “Ephebos”, ed. and trans. Wolfgang Jöhling (Berlin: Verlag rosa Winkel, 1993).

[4] Teresa Chylinska, “Karol Szymanowski,” The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie (London: Macmillan, 1980), p. 499. The date given here seems to be the most commonly accepted.

[5] Christopher Palmer, Szymanowski (London: British Broadcasting Corporation, 1983), p. 25.

[6] Teresa Chylinska, “Karol Szymanowski,” The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie (London: Macmillan, 1980), p. 501.

[7] Jim Samson, The Music of Szymanowski (London: Kahn & Averill, 1981), pp. 149–150.

[8] Jim Samson, The Music of Szymanowski (London: Kahn & Averill, 1981), p. 150.

[9] Teresa Chylinska, “Karol Szymanowski,” The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie (London: Macmillan, 1980), p. 500.

[10] Christopher Palmer, Szymanowski (London: British Broadcasting Corporation, 1983), p. 28.

[11] Arthur Rubinstein, My Many Years (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1980), p. 103.

[12] Hans Bethge (1876–1946) also translated the Chinese poems used by Gustav Mahler as text for Das Lied von der Erde. In 1903 Bethge published an article on the German painter Fidus in the homosexual journal Der Eigene.

[13] Teresa Chylinska, “Karol Szymanowski,” The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie (London: Macmillan, 1980), p. 500.

[14] After several changes of name, this town became Kirovograd in 1939.

[15] B. M. Maciejewski, Karol Szymanowski: His Life and Music (London: Poets’ and Painters’ Press, 1967), pp. 61–62.

[16] Karol Szymanowski, Das Gastmahl: Ein Kapitel aus dem Roman “Ephebos”, ed. and trans. Wolfgang Jöhling (Berlin: Verlag rosa Winkel, 1993), p. 117.

[17] Richard Buckle, Diaghilev (London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1979), p. 3.

[18] Boris Kochno, Christian Bérard (London: Thames and Hudson, 1988), p. 12. It should be noted

that if Kochno was “nearly seventeen” when he met Diaghilev, then he was born in 1904, not 1903 as given by Jöhling in Das Gastmahl. Apparently, Kochno was not consistent in reporting his birth year: some reference works give 1903; The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Ballet has 3 January 1904. [Added 2003 in an online note at https://hubertkennedy.angelfire.com/Four.pdf: The obvious solution to this discrepancy is that his birth year was 1904 in the Gregorian calendar, but 1903 in the Julian calendar, which was still in use in Moscow when Kochno was born there.]

[19] Arthur Rubinstein, My Many Years (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1980), pp. 104-105. Rubinstein’s chronology is again faulty; he placed this meeting before Szymanowski’s first trip to the United States.

[20] Richard Buckle, Diaghilev (London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1979), p. 377.

[21] Richard Buckle, In the Wake of Diaghilev (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1983), pp. 21–22.

[22] Richard Buckle, In the Wake of Diaghilev (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1983), p. 41.

[23] Edmund White, Jean Genet: A Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1993), p. 262. White referred to Kochno as “Bérard’s lover” (ibid., p. 213).

[24] Karol Szymanowski and Jan Smeterlin: Correspondence and Essays, trans. and ed. B. M. Maciejewski and Felix Aprahamian (London: Allegro Press, 1970), p. 37.

[25] Karol Szymanowski and Jan Smeterlin: Correspondence and Essays, trans. and ed. B. M. Maciejewski and Felix Aprahamian (London: Allegro Press, 1970), pp. 44–45.

[26] Arthur Rubinstein, My Many Years (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1980), p. 411.

[27] Karol Szymanowski, Das Gastmahl: Ein Kapitel aus dem Roman “Ephebos”, ed. and trans. Wolfgang Jöhling (Berlin: Verlag rosa Winkel, 1993), p. 34.

[28] Karol Szymanowski, Das Gastmahl: Ein Kapitel aus dem Roman “Ephebos”, ed. and trans. Wolfgang Jöhling (Berlin: Verlag rosa Winkel, 1993), p. 122.

[29] In his memoir, Iwaszkiewicz listed them from memory (see Karol Szymanowski, Das Gastmahl: Ein Kapitel aus dem Roman “Ephebos”, ed. and trans. Wolfgang Jöhling (Berlin: Verlag rosa Winkel, 1993), pp. 18–19), but his list is only partly correct.

[30] A photograph of the title page is included in Karol Szymanowski, Das Gastmahl: Ein Kapitel aus dem Roman “Ephebos”, ed. and trans. Wolfgang Jöhling (Berlin: Verlag rosa Winkel, 1993), p. 21. In ancient Greece, the term “ephebos” was generally used for a youth in his late teens; in Athens it was legally an eighteen-year-old.

[31] Der Eigene (The Self-Owner) was begun in 1896 as an anarchist journal, in the direction of the individualist philosophy of Max Stirner; its title reflects the meaning Stirner gave the word eigen. It was openly homosexual from 1898 and lasted until 1931. Its authors, many of them boy-lovers, “rejected the mounting influence of doctors and psychiatrists in the gay movement, and argued that love and friendship between older and younger males provided the basis for a higher level of social organization (the Männerbund) than was afforded by the purely sexual, private bonds characteristic of that most primitive social unit, the family. Yet their belief in bisexuality was genuine and most of the pederast leaders ... were married.” David Thorstad, “For Friendship and Freedom,” Gayme (Boston), issue 1.2 (1994), p. 5. According to Thorstad, “The modern man-boy love movement can trace its roots to an article from 1899 [in Der Eigene] by the painter and poet Elisar von Kupffer (1872–1942): ‘The Ethical-Political Significance of Lieblingminne’” (op. cit., p. 6).

[32] Karol Szymanowski, Das Gastmahl: Ein Kapitel aus dem Roman “Ephebos”, ed. and trans. Wolfgang Jöhling (Berlin: Verlag rosa Winkel, 1993), p. 57.

[33] Karol Szymanowski, Das Gastmahl: Ein Kapitel aus dem Roman “Ephebos”, ed. and trans. Wolfgang Jöhling (Berlin: Verlag rosa Winkel, 1993), p. 69.

[34] Karol Szymanowski, Das Gastmahl: Ein Kapitel aus dem Roman “Ephebos”, ed. and trans. Wolfgang Jöhling (Berlin: Verlag rosa Winkel, 1993), pp. 86–87.

[35] Karol Szymanowski, Das Gastmahl: Ein Kapitel aus dem Roman “Ephebos”, ed. and trans. Wolfgang Jöhling (Berlin: Verlag rosa Winkel, 1993), p. 124.

[36] Karol Szymanowski, Das Gastmahl: Ein Kapitel aus dem Roman “Ephebos”, ed. and trans. Wolfgang Jöhling (Berlin: Verlag rosa Winkel, 1993), pp. 125-6.

Comments powered by CComment