THE PHAIDROS BY PLATO

The Phaidros was a dialogue between Athenians about erotic love composed roughly around 370 BC by Plato (427-347 BC), the pre-eminent philosopher of antiquity.

Unlike Plato’s other dialogues, it has only two participants, Plato’s revered teacher Sokrates and the Phaidros of the title, though the latter repeats a speech by the absent orator Lysias. That the manner of discussion depicted was indeed Socrates’s is attested by others who knew him, but it is not known to what degree the views ascribed to him in the Phaidros were his, as opposed to Plato’s own.

The setting is the countryside outside Athens some time between 412 BC (when Lysias first came to Athens as an adult) and 399 BC, when Sokrates died.

Though principally about erotic love, the subject with which it begins, it digresses into other topics. Presented here is the third of the work which really is about love. As it is assumed without need for explanation in the dialogue that the romantic love under discussion is the love of a man and a boy, this third is all of pederastic interest. To provide both continuity and context, a brief synopsis is given of all the omitted passages.

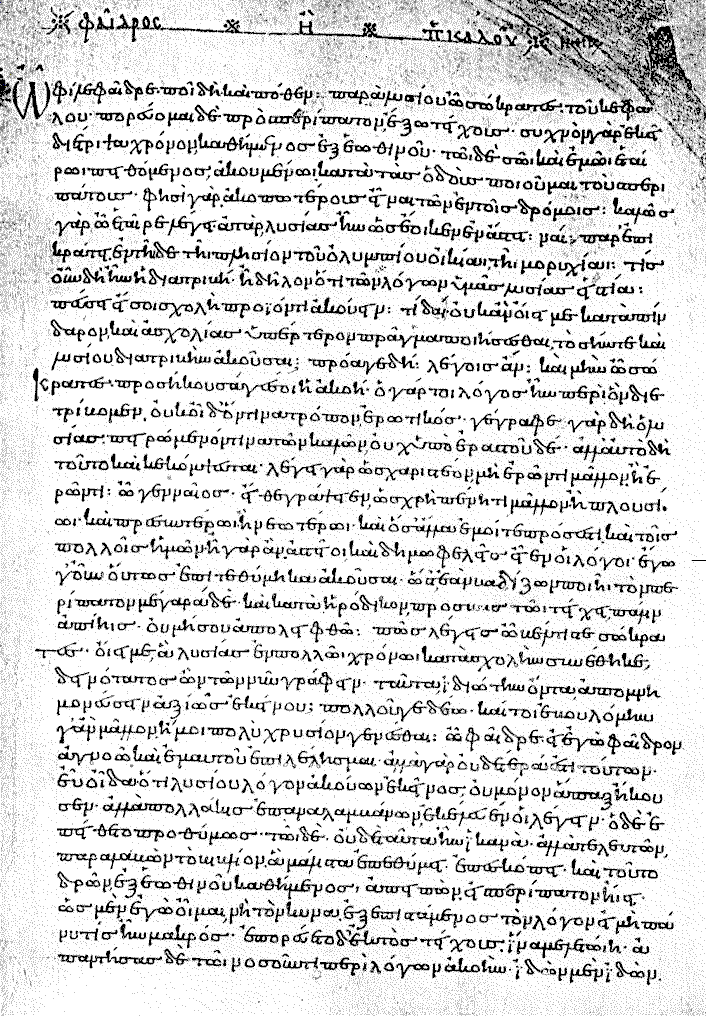

The Greek text is from the Loeb Classical Library volume XXXVI (Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1914). The translation is by Alexander Nehamas and Paul Woodruff in Plato: Complete Works, edited by John M. Cooper (Indianapolis, 1997).

| Phaidros |

Φαῖδρος |

Socrates meets Phaedrus going for a walk outside the city wall after having listened to a long speech by Lysias in Epikrates’s house near the Olympieion. Phaedrus agrees to Sokrates’s request to hear what Lysis said (227a-c).

227c-d

|

PHAEDRUS: In fact, Socrates, you’re just the right person to hear the speech that occupied us, since, in a roundabout way, it was about love. It is aimed at seducing a beautiful boy, but the speaker is not in love with him—this is actually what is so clever and elegant about it: Lysias argues that it is better to give your favors to someone who does not love you than to someone who does. SOCRATES: What a wonderful man! I wish he would write that you should give your favors to a poor rather than to a rich man, to an older rather than to a younger one—that is, to someone like me and most other people: then his speeches would be really sophisticated, and they’d contribute to the public good besides! In any case, I am so eager to hear it that I would follow you even if you were walking all the way to Megara, as Herodicus recommends, to touch the wall and come back again.[1]  |

ΦΑΙΔΡΟΣ: Καὶ μήν, ὦ Σώκρατες, προσήκουσά γέ σοι ἡ ἀκοή. ὁ γάρ τοι λόγος ἦν, περὶ ὃν διετρίβομεν. οὐκ οἶδ᾿ ὅντινα τρόπον ἐρωτικός. γέγραφε γὰρ δὴ ὁ Λυσίας πειρώμενόν τινα τῶν καλῶν, οὐχ ὑπ᾿ ἐραστοῦ δέ, ἀλλ᾿ αὐτὸ δὴ τοῦτο καὶ κεκόμψευται· λέγει γὰρ ὡς χαριστέον μὴ ἐρῶντι μᾶλλον ἢ ἐρῶντι. ΣΩΚΡΑΤΗΣ: Ὢ γενναῖος, εἴθε γράψειεν ὡς χρὴ πένητι μᾶλλον ἢ πλουσίῳ, καὶ πρεσβυτέρῳ ἢ νεωτέρῳ, καὶ ὅσα ἄλλα [d] ἐμοί τε πρόσεστι καὶ τοῖς πολλοῖς ἡμῶν· ἦ γὰρ ἂν ἀστεῖοι καὶ δημωφελεῖς εἶεν οἱ λόγοι. ἔγωγ᾿ οὖν οὕτως ἐπιτεθύμηκα ἀκοῦσαι, ὥστ᾿ ἐὰν βαδίζων ποιῇ τὸν περίπατον Μέγαράδε, καὶ κατὰ Ἡρόδικον προσβὰς τῷ τείχει πάλιν ἀπίῃς, οὐ μή σου ἀπολειφθῶ.  |

Phaedrus makes various excuses why he cannot recount Lysias’s speech verbatim until Socrates challenges him with his suspicion that he had it written out and hidden in his left hand, under his cloak. Phaedrus then agrees to read it to him once they have walked through the nearby brook until they have found an agreeable spot in the shade. This done, Phaedrus began his rendition:

230e-234c

|

PHAEDRUS: Listen, then: You understand my situation: I’ve told you how good it would be for us, in my opinion, if this worked out. In any case, I don’t think I should lose the chance to get what I am asking for, merely because I don’t happen to be in love with you. A man in love will wish he had not done you any favors once his desire dies down, but the time will never come for a man who’s not in love to change his mind. That is because the favors he does for you are not forced but voluntary; and he does the best that he possibly can for you, just as he would for his own business. Besides, a lover keeps his eye on the balance sheet where his interests have suffered from love, and where he has done well; and when he adds up all the trouble he has taken, he thinks he’s long since given the boy he loved a fair return. A non lover, on the other hand, can’t complain about love’s making him neglect his own business; he can’t keep a tab on the trouble he’s been through, or blame you for the quarrels he’s had with his relatives. Take away all those headaches and there’s nothing left for him to do but put his heart into whatever he thinks will give pleasure. Besides, suppose a lover does deserve to be honored because, as they say, he is the best friend his loved one will ever have, and he stands ready to please his boy with all those words and deeds that are so annoying to everyone else. It’s easy to see (if he is telling the truth) that the next time he falls in love he will care more for his new love than for the old one, and it’s clear he’ll treat the old one shabbily whenever that will please the new one. And anyway, what sense does it make to throw away something like that on a person who has fallen into such a miserable condition that those who have suffered it don’t even try to defend themselves against it? A lover will admit that he’s more sick than sound in the head. He’s well aware that he is not thinking straight; but he’ll say he can’t get himself under control. So when he does start thinking straight, why would he stand by decisions he had made when he was sick? Another point: if you were to choose the best of those who are in love with you, you’d have a pretty small group to pick from; but you’ll have a large group if you don’t care whether he loves you or not and just pick the one who suits you best; and in that larger pool you’ll have a much better hope of finding someone who deserves your friendship. Now suppose you’re afraid of conventional standards and the stigma that will come to you if people find out about this. Well, it stands to reason that a lover thinking that everyone else will admire him for his success as much as he admires himself—will fly into words and proudly declare to all and sundry that his labors were not in vain. Someone who does not love you, on the other hand, can control himself and will choose to do what is best, rather than seek the glory that comes from popular reputation. Besides, it’s inevitable that a lover will be found out: many people will see that he devotes his life to following the boy he loves. The result is that whenever people see you talking with him they’ll think you are spending time together just before or just after giving way to desire. But they won’t even begin to find fault with people for spending time together if they are not lovers; they know one has to talk to someone, either out of friendship or to obtain some other pleasure. Another point: have you been alarmed by the thought that it is hard for friendships to last? Or that when people break up, it’s ordinarily just as awful for one side as it is for the other, but when you’ve given up what is most important to you already, then your loss is greater than his? If so, it would make more sense for you to be afraid of lovers. For a lover is easily annoyed, and whatever happens, he’ll think it was designed to hurt him. That is why a lover prevents the boy he loves from spending time with other people. He’s afraid that wealthy men will outshine him with their money, while men of education will turn out to have the advantage of greater intelligence. And he watches like a hawk everyone who may have any other advantage over him! Once he’s persuaded you to turn those people away, he’ll have you completely isolated from friends; and if you show more sense than he does in looking after your own interests, you’ll come to quarrel with him. But if a man really does not love you, if it is only because of his excellence that he got what he asked for, then he won’t be jealous of the people who spend time with you. Quite the contrary! He’ll hate anyone who does not want to be with you; he’ll think they look down on him while those who spend time with you do him good; so you should expect friendship, rather than enmity, to result from this affair. Another point: lovers generally start to desire your body before they know your character or have any experience of your other traits, with the result that even they can’t tell whether they’ll still want to be friends with you after their desire has passed. Non-lovers, on the other hand, are friends with you even before they achieve their goal, and you’ve no reason to expect that benefits received will ever detract from their friendship for you. No, those things will stand as reminders of more to come. Another point: you can expect to become a better person if you are won over by me, rather than by a lover. A lover will praise what you say and what you do far beyond what is best, partly because he is afraid of being disliked, and partly because desire has impaired his judgment. Here is how love draws conclusions: When a lover suffers a reverse that would cause no pain to anyone else, love makes him think he’s accursed! And when he has a stroke of luck that’s not worth a moment’s pleasure, love compels him to sing its praises. The result is, you should feel sorry for lovers, not admire them. If my argument wins you over, I will, first of all, give you my time with no thought of immediate pleasure; I will plan instead for the benefits that are to come, since I am master of myself and have not been overwhelmed by love. Small problems will not make me very hostile, and big ones will make me only gradually, and only a little, angry. I will forgive you for unintentional errors and do my best to keep you from going wrong intentionally. All this, you see, is the proof of a friendship that will last a long time. Have you been thinking that there can be no strong friendship in the absence of erotic love? Then you ought to remember that we would not care so much about our children if that were so, or about our fathers and mothers. And we wouldn’t have had any trustworthy friends, since those relationships did not come from such a desire but from doing quite different things. Besides, if it were true that we ought to give the biggest favor to those who need it most, then we should all be helping out the very poorest people, not the best ones, because people we’ve saved from the worst troubles will give us the most thanks. For instance, the right people to invite to a dinner party would be beggars and people who need to sate their hunger, because they’re the ones who’ll be fond of us, follow us, knock on our doors,[2] take the most pleasure with the deepest gratitude, and pray for our success. No, it’s proper, I suppose, to grant your favors to those who are best able to return them, not to those in the direst need— that is, not to those who merely desire the thing, but to those who really deserve it—not to people who will take pleasure in the bloom of your youth, but to those who will share their goods with you when you are older; not to people who achieve their goal and then boast about it in public, but to those who will keep a modest silence with everyone; not to people whose devotion is short-lived, but to those who will be steady friends their whole lives; not to the people who look for an excuse to quarrel as soon as their desire has passed, but to those who will prove their worth when the bloom of your youth has faded. Now, remember what I said and keep this in mind: friends often criticize a lover for bad behavior; but no one close to a non-lover ever thinks that desire has led him into bad judgment about his interests. And now I suppose you’ll ask me whether I’m urging you to give your favors to everyone who is not in love with you. No. As I see it, a lover would not ask you to give in to all your lovers either. You would not, in that case, earn as much gratitude from each recipient, and you would not be able to keep one affair secret from the others in the same way. But this sort of thing is not supposed to cause any harm, and really should work to the benefit of both sides. Well, I think this speech is long enough. If you are still longing for more, if you think I have passed over something, just ask. How does the speech strike you, Socrates? Don’t you think it’s simply superb, especially in its choice of words?  |

ΦΑΙΔΡΟΣ: Ἄκουε δή. Περὶ μὲν τῶν ἐμῶν πραγμάτων ἐπίστασαι, καὶ ὡς νομίζω συμφέρειν ἡμῖν γενομένων τούτων ἀκήκοας· ἀξιῶ δὲ μὴ διὰ [231a] τοῦτο ἀτυχῆσαι ὧν δέομαι, ὅτι οὐκ ἐραστὴς ὤν σου τυγχάνω. ὡς ἐκείνοις μὲν τότε μεταμέλει ὧν ἂν εὖ ποιήσωσιν, ἐπειδὰν τῆς ἐπιθυμίας παύσωνται· τοῖς δὲ οὐκ ἔστι χρόνος, ἐν ᾧ μεταγνῶναι προσήκει. οὐ γὰρ ὑπ᾿ ἀνάγκης ἀλλ᾿ ἑκόντες, ὡς ἂν ἄριστα περὶ τῶν οἰκείων βουλεύσαιντο, πρὸς τὴν δύναμιν τὴν αὐτῶν εὖ ποιοῦσιν. ἔτι δὲ οἱ μὲν ἐρῶντες σκοποῦσιν ἅ τε κακῶς διέθεντο τῶν αὑτῶν διὰ τὸν ἔρωτα καὶ ἃ πεποιήκασιν εὖ, καὶ ὃν εἶχον πόνον προστιθέντες [b] ἡγοῦνται πάλαι τὴν ἀξίαν ἀποδεδωκέναι χάριν τοῖς ἐρωμένοις· τοῖς δὲ μὴ ἐρῶσιν οὔτε τὴν τῶν οἰκείων ἀμέλειαν διὰ τοῦτο ἔστι προφασίζεσθαι, οὔτε τοὺς παρεληλυθότας πόνους ὑπολογίζεσθαι, οὔτε τὰς πρὸς τοὺς προσήκοντας διαφορὰς αἰτιάσασθαι· ὥστε περιῃρημένων τοσούτων κακῶν οὐδὲν ὑπολείπεται ἀλλ᾿ ἢ ποιεῖν προθύμως, ὅ τι ἂν αὐτοῖς οἴωνται πράξαντες χαριεῖσθαι. ἔτι δὲ εἰ διὰ τοῦτο ἄξιον [c] τοὺς ἐρῶντας περὶ πολλοῦ ποιεῖσθαι, ὅτι τούτους μάλιστά φασι φιλεῖν ὧν ἂν ἐρῶσιν καὶ ἕτοιμοί εἰσι καὶ ἐκ τῶν λόγων καὶ ἐκ τῶν ἔργων τοῖς ἄλλοις ἀπεχθανόμενοι τοῖς ἐρωμένοις χαρίζεσθαι, ῥᾴδιον γνῶναι, εἰ ἀληθῆ λέγουσιν, ὅτι ὅσων ἂν ὕστερον ἐρασθῶσιν, ἐκείνους αὐτῶν περὶ πλείονος ποιήσονται, καὶ δῆλον ὅτι, ἐὰν ἐκείνοις δοκῇ, καὶ τούτους κακῶς ποιήσουσι. καί τοι πῶς εἰκός ἐστι τοιοῦτον πρᾶγμα προέσθαι [d] τοιαύτην ἔχοντι συμφοράν, ἣν οὐδ᾿ ἂν ἐπιχειρήσειεν οὐδεὶς ἔμπειρος ὢν ἀποτρέπειν; καὶ γὰρ αὐτοὶ ὁμολογοῦσιν νοσεῖν μᾶλλον ἢ σωφρονεῖν, καὶ εἰδέναι ὅτι κακῶς φρονοῦσιν, ἀλλ᾿ οὐ δύνασθαι αὑτῶν κρατεῖν· ὥστε πῶς ἂν εὖ φρονήσαντες ταῦτα καλῶς ἔχειν ἡγήσαιντο περὶ ὧν οὕτω διακείμενοι βεβούλευνται; καὶ μὲν δὴ εἰ μὲν ἐκ τῶν ἐρώντων τὸν βέλτιστον αἱροῖο, ἐξ ὀλίγων ἄν σοι ἡ ἔκλεξις εἴη· εἰ δ᾿ ἐκ τῶν ἄλλων τὸν σαυτῷ ἐπιτηδειότατον, ἐκ πολλῶν· ὥστε πολὺ [e] πλείων ἐλπὶς ἐν τοῖς πολλοῖς ὄντα τυχεῖν τὸν ἄξιον τῆς σῆς φιλίας. Εἰ τοίνυν τὸν νόμον τὸν καθεστηκότα δέδοικας, μὴ πυθομένων τῶν ἀνθρώπων ὄνειδός σοι γένηται, εἰκός ἐστι [232a] τοὺς μὲν ἐρῶντας, οὕτως ἂν οἰομένους καὶ ὑπὸ τῶν ἄλλων ζηλοῦσθαι ὥσπερ αὐτοὺς ὑφ᾿ αὑτῶν, ἐπαρθῆναι τῷ ἔχειν καὶ φιλοτιμουμένους ἐπιδείκνυσθαι πρὸς ἅπαντας, ὅτι οὐκ ἄλλως αὐτοῖς πεπόνηται· τοὺς δὲ μὴ ἐρῶντας, κρείττους αὑτῶν ὄντας, τὸ βέλτιστον ἀντὶ τῆς δόξης τῆς παρὰ τῶν ἀνθρώπων αἱρεῖσθαι. ἔτι δὲ τοὺς μὲν ἐρῶντας πολλοὺς ἀνάγκη πυθέσθαι καὶ ἰδεῖν, ἀκολουθοῦντας τοῖς ἐρωμένοις καὶ ἔργον τοῦτο ποιουμένους, ὥστε ὅταν ὀφθῶσι διαλεγόμενοι [b] ἀλλήλοις, τότε αὐτοὺς οἴονται ἢ γεγενημένης ἢ μελλούσης ἔσεσθαι τῆς ἐπιθυμίας συνεῖναι· τοὺς δὲ μὴ ἐρῶντας οὐδ᾿ αἰτιᾶσθαι διὰ τὴν συνουσίαν ἐπιχειροῦσιν, εἰδότες ὅτι ἀναγκαῖόν ἐστιν ἢ διὰ φιλίαν τῳ διαλέγεσθαι ἢ δι᾿ ἄλλην τινὰ ἡδονήν. καὶ μὲν δὴ εἴ σοι δέος παρέστηκεν ἡγουμένῳ χαλεπὸν εἶναι φιλίαν συμμένειν, καὶ ἄλλῳ μὲν τρόπῳ διαφορᾶς γενομένης κοινὴν ἂν ἀμφοτέροις καταστῆναι τὴν [c] συμφοράν, προεμένου δέ σου ἃ περὶ πλείστου ποιεῖ μεγάλην δὴ σοι βλάβην ἂν γενέσθαι, εἰκότως δὴ τοὺς ἐρῶντας μᾶλλον ἂν φοβοῖο· πολλὰ γὰρ αὐτούς ἐστι τὰ λυποῦντα, καὶ πάντ᾿ ἐπὶ τῇ αὑτῶν βλάβῃ νομίζουσι γίγνεσθαι. διόπερ καὶ τὰς πρὸς τοὺς ἄλλους τῶν ἐρωμένων συνουσίας ἀποτρέπουσιν, φοβούμενοι τοὺς μὲν οὐσίαν κεκτημένους, μὴ χρήμασιν αὐτοὺς ὑπερβάλωνται, τοὺς δὲ πεπαιδευμένους, μὴ συνέσει κρείττους γένωνται· τῶν δ᾿ ἄλλο τι κεκτημένων [d] ἀγαθὸν τὴν δύναμιν ἑκάστου φυλάττονται. πείσαντες μὲν οὖν ἀπέχθεσθαί σε τούτοις εἰς ἐρημίαν φίλων καθιστᾶσιν, ἐὰν δὲ τὸ σεαυτοῦ σκοπῶν ἄμεινον ἐκείνων φρονῇς, ἥξεις αὐτοῖς εἰς διαφοράν· ὅσοι δὲ μὴ ἐρῶντες ἔτυχον, ἀλλὰ δι᾿ ἀρετὴν ἔπραξαν ὧν ἐδέοντο, οὐκ ἂν τοῖς συνοῦσι φθονοῖεν, ἀλλὰ τους μὴ ἐθέλοντας μισοῖεν, ἡγούμενοι σ᾿ ὑπ᾿ ἐκείνων μὲν ὑπερορᾶσθαι, ὑπὸ τῶν συνόντων δὲ ὠφελεῖσθαι, ὥστε πολὺ [e] πλείων ἐλπὶς φιλίαν αὐτοῖς ἐκ τοῦ πράγματος ἢ ἔχθραν γενήσεσθαι.  Καὶ μὲν δὴ τῶν μὲν ἐρώντων πολλοὶ πρότερον τοῦ σώματος ἐπεθύμησαν ἢ τὸν τρόπον ἔγνωσαν καὶ τῶν ἄλλων οἰκείων ἔμπειροι ἐγένοντο, ὥστε ἄδηλον εἰ ἔτι βουλήσονται φίλοι εἶναι, ἐπειδὰν τῆς ἐπιθυμίας παύσωνται· [233a] τοῖς δὲ μὴ ἐρῶσιν, οἳ καὶ πρότερον ἀλλήλοις φίλοι ὄντες ταῦτα ἔπραξαν, οὐκ ἐξ ὧν ἂν εὖ πάθωσι ταῦτα εἰκός ἐλάττω τὴν φιλίαν αὐτοῖς ποιῆσαι, ἀλλὰ ταῦτα μνημεῖα καταλειφθῆναι τῶν μελλόντων ἔσεσθαι. καὶ μὲν δὴ βελτίονί σοι προσήκει γενέσθαι ἐμοὶ πειθομένῳ ἢ ἐραστῇ. ἐκεῖνοι μὲν γὰρ καὶ παρὰ τὸ βέλτιστον τά τε λεγόμενα καὶ τὰ πραττόμενα ἐπαινοῦσι, τὰ μὲν δεδιότες μὴ ἀπέχθωνται, τὰ δὲ [b] καὶ αὐτοὶ χεῖρον διὰ τὴν ἐπιθυμίαν γιγνώσκοντες. τοιαῦτα γὰρ ὁ ἔρως ἐπιδείκνυται· δυστυχοῦντας μέν, ἃ μὴ λύπην τοῖς ἄλλοις παρέχει, ἀνιαρὰ ποιεῖ νομίζειν· εὐτυχοῦντας δὲ καὶ τὰ μὴ ἡδονῆς ἄξια παρ᾿ ἐκείνων ἐπαίνου ἀναγκάζει τυγχάνειν· ὥστε πολὺ μᾶλλον ἐλεεῖν τοὺς ἐρωμένους ἢ ζηλοῦν αὐτοὺς προσήκει. ἐὰν δ᾿ ἐμοὶ πείθῃ, πρῶτον μὲν οὐ τὴν παροῦσαν ἡδονὴν θεραπεύων συνέσομαί σοι, ἀλλὰ καὶ [c] τὴν μέλλουσαν ὠφελίαν ἔσεσθαι, οὐχ ὑπ᾿ ἔρωτος ἡττώμενος, ἀλλ᾿ ἐμαυτοῦ κρατῶν, οὐδὲ διὰ σμικρὰ ἰσχυρὰν ἔχθραν ἀναιρούμενος, ἀλλὰ διὰ μεγάλα βραδέως ὀλίγην ὀργὴν ποιούμενος, τῶν μὲν ἀκουσίων συγγνώμην ἔχων, τὰ δὲ ἑκούσια πειρώμενος ἀποτρέπειν· ταῦτα γάρ ἐστι φιλίας πολὺν χρόνον ἐσομένης τεκμήρια. εἰ δ᾿ ἄρα σοι τοῦτο παρέστηκεν, ὡς οὐχ οἷόν τε ἰσχυρὰν φιλίαν γενέσθαι, ἐὰν μή τις ἐρῶν τυγχάνῃ, [d] ἐνθυμεῖσθαι χρή, ὅτι οὔτ᾿ ἂν τοὺς υἱεῖς περὶ πολλοῦ ἐποιούμεθα οὔτ᾿ ἂν τοὺς πατέρας καὶ τὰς μητέρας, οὔτ᾿ ἂν πιστοὺς φίλους ἐκεκτήμεθα, οἳ οὐκ ἐξ ἐπιθυμίας τοιαύτης γεγόνασιν ἀλλ᾿ ἐξ ἑτέρων ἐπιτηδευμάτων. Ἔτι δὲ εἰ χρὴ τοῖς δεομένοις μάλιστα χαρίζεσθαι, προσήκει καὶ τῶν ἄλλων μὴ τοὺς βελτίστους ἀλλὰ τοὺς ἀπορωτάτους εὖ ποιεῖν· μεγίστων γὰρ ἀπαλλαγέντες κακῶν πλείστην χάριν αὐτοῖς εἴσονται. καὶ μὲν δὴ καὶ ἐν ταῖς [e] ἰδίαις δαπάναις οὐ τοὺς φίλους ἄξιον παρακαλεῖν, ἀλλὰ τοὺς προσαιτοῦντας καὶ τοὺς δεομένους πλησμονῆς· ἐκεῖνοι γὰρ καὶ ἀγαπήσουσιν καὶ ἀκολουθήσουσιν καὶ ἐπὶ τὰς θύρας ἥξουσιν καὶ μάλιστα ἡσθήσονται καὶ οὐκ ἐλαχίστην χάριν εἴσονται καὶ πολλὰ ἀγαθὰ αὐτοῖς εὔξονται. ἀλλ᾿ ἴσως προσήκει οὐ τοῖς σφόδρα δεομένοις χαρίζεσθαι, ἀλλὰ τοῖς μάλιστα ἀποδοῦναι χάριν δυναμένοις· οὐδὲ τοῖς προσαιτοῦσι [234a] μόνον, ἀλλὰ τοῖς τοῦ πράγματος ἀξίοις· οὐδὲ ὅσοι τῆς σῆς ὥρας ἀπολαύσονται, ἀλλ᾿ οἵ τινες πρεσβυτέρῳ γενομένῳ τῶν σφετέρων ἀγαθῶν μεταδώσουσιν· οὐδὲ οἳ διαπραξάμενοι πρὸς τοὺς ἄλλους φιλοτιμήσονται, ἀλλ᾿ οἵ τινες αἰσχυνόμενοι πρὸς ἅπαντας σιωπήσονται· οὐδὲ τοῖς ὀλίγον χρόνον σπουδάζουσιν, ἀλλὰ τοῖς ὁμοίως διὰ παντὸς τοῦ βίου φίλοις ἐσομένοις· οὐδὲ οἵ τινες παυόμενοι τῆς ἐπιθυμίας ἔχθρας πρόφασιν ζητήσουσιν, ἀλλ᾿ οἳ παυσαμένοις τῆς ὥρας τότε [b] τὴν αὑτῶν ἀρετὴν ἐπιδείξονται. σὺ οὖν τῶν τε εἰρημένων μέμνησο, καὶ ἐκεῖνο ἐνθυμοῦ, ὅτι τοὺς μὲν ἐρῶντας οἱ φίλοι νουθετοῦσιν ὡς ὄντος κακοῦ τοῦ ἐπιτηδεύματος, τοῖς δὲ μὴ ἐρῶσιν οὐδεὶς πώποτε τῶν οἰκείων ἐμέμψατο ὡς διὰ τοῦτο κακῶς βουλευομένοις περὶ ἑαυτῶν. Ἴσως μὲν οὖν ἂν ἔροιό με, εἰ ἅπασίν σοι παραινῶ τοῖς μὴ ἐρῶσι χαρίζεσθαι. ἐγὼ δὲ οἶμαι οὐδ᾿ ἂν τὸν ἐρῶντα πρὸς ἅπαντάς σε κελεύειν τοὺς ἐρῶντας ταύτην ἔχειν τὴν [c] διάνοιαν. οὔτε γὰρ τῷ λόγῳ λαμβάνοντι χάριτος ἴσης ἄξιον, οὔτε σοὶ βουλομένῳ τοὺς ἄλλους λανθάνειν ὁμοίως δυνατόν· δεῖ δὲ βλάβην μὲν ἀπ᾿ αὐτοῦ μηδεμίαν, ὠφελίαν δὲ ἀμφοῖν γίγνεσθαι. ἐγὼ μὲν οὖν ἱκανά μοι νομίζω τὰ εἰρημένα. εἰ δέ τι σὺ ποθεῖς, ἡγούμενος παραλελεῖφθαι, ἐρώτα. Τί σοι φαίνεται, ὦ Σώκρατες, ὁ λόγος; οὐχ ὑπερφυῶς τά τε ἄλλα καὶ τοῖς ὀνόμασιν εἰρῆσθαι; |

Socrates claims to be overcome by the speech, but Phaedrus detects his subtle sarcasm and asks him not to joke. Socrates says Lysias was repetitious and he could do better. However, he refuses to do so until Phaedrus says he will never recite another speech for him unless he does. After appealing to the Muses for help, Socrates proceeds:

237b-244a

|

SOCRATES: There once was a boy, a youth rather, and he was very beautiful, and had very many lovers. One of them was wily and had persuaded him that he was not in love, though he loved the lad no less than the others. And once in pressing his suit to him, he tried to persuade him that he ought to give his favors to a man who did not love him rather than to one who did. And this is what he said: “If you wish to reach a good decision on any topic, my boy, there is only one way to begin: You must know what the decision is about, or else you are bound to miss your target altogether. Ordinary people cannot see that they do not know the true nature of a particular subject, so they proceed as if they did; and because they do not work out an agreement at the start of the inquiry, they wind up as you would expect—in conflict with themselves and each other. Now you and I had better not let this happen to us, since we criticize it in others. Because you and I are about to discuss whether a boy should make friends with a man who loves him rather than with one who does not, we should agree on defining what love is and what effects it has. Then we can look back and refer to that as we try to find out whether to expect benefit or harm from love. Now, as everyone plainly knows, love is some kind of desire; but we also know that even men who are not in love have a desire for what is beautiful. So how shall we distinguish between a man who is in love and one who is not? We must realize that each of us is ruled by two principles which we follow wherever they lead: one is our inborn desire for pleasures, the other is our acquired judgment that pursues what is best. Sometimes these two are in agreement; but there are times when they quarrel inside us, and then sometimes one of them gains control, sometimes the other. Now when judgment is in control and leads us by reasoning toward what is best, that sort of self-control is called ‘being in your right mind’; but when desire takes command in us and drags us without reasoning toward pleasure, then its command is known as ‘outrageousness’.[3] Now outrageousness has as many names as the forms it can take, and these are quite diverse. Whichever form stands out in a particular case gives its name to the person who has it—and that is not a pretty name to be called, not worth earning at all. If it is desire for food that overpowers a person’s reasoning about what is best and suppresses his other desires, it is called gluttony and it gives him the name of a glutton, while if it is desire for drink that plays the tyrant and leads the man in that direction, we all know what name we’ll call him then! And now it should be clear how to describe someone appropriately in the other cases: call the man by that name sister to these others—that derives from the sister of these desires that controls him at the time. As for the desire that has led us to say all this, it should be obvious already, but I suppose things said are always better understood than things unsaid: The unreasoning desire that overpowers a person’s considered impulse to do right and is driven to take pleasure in beauty, its force reinforced by its kindred desires for beauty in human bodies— this desire, all conquering in its forceful drive, takes its name from the word for force (rhōmē) and is called erōs.”[4] There, Phaedrus my friend, don’t you think, as I do, that I’m in the grip of something divine? PHAEDRUS: This is certainly an unusual flow of words for you, Socrates. SOCRATES: Then be quiet and listen. There’s something really divine about this place, so don’t be surprised if I’m quite taken by the Nymphs’ madness as I go on with the speech. I’m on the edge of speaking in dithyrambs[5] as it is. PHAEDRUS: Very true! SOCRATES: Yes, and you’re the cause of it. But hear me out; the attack may yet be prevented. That, however, is up to the god; what we must do is face the boy again in the speech: “All right then, my brave friend, now we have a definition for the subject of our decision; now we have said what it really is; so let us keep that in view as we complete our discussion. What benefit or harm is likely to come from the lover or the non-lover to the boy who gives him favors? It is surely necessary that a man who is ruled by desire and is a slave to pleasure will turn his boy into whatever is most pleasing to himself. Now a sick man takes pleasure in anything that does not resist him, but sees anyone who is equal or superior to him as an enemy. That is why a lover will not willingly put up with a boyfriend who is his equal or superior, but is always working to make the boy he loves weaker and inferior to himself. Now, the ignorant man is inferior to the wise one, the coward to the brave, the ineffective speaker to the trained orator, the slow-witted to the quick. By necessity, a lover will be delighted to find all these mental defects and more, whether acquired or innate in his boy; and if he does not, he will have to supply them or else lose the pleasure of the moment. The necessary consequence is that he will be jealous and keep the boy away from the good company of anyone who would make a better man of him; and that will cause him a great deal of harm, especially if he keeps him away from what would most improve his mind—and that is, in fact, divine philosophy, from which it is necessary for a lover to keep his boy a great distance away, out of fear the boy will eventually come to look down on him. He will have to invent other ways, too, of keeping the boy in total ignorance and so in total dependence on himself. That way the boy will give his lover the most pleasure, though the harm to himself will be severe. So it will not be of any use to your intellectual development to have as your mentor and companion a man who is in love. “Now let’s turn to your physical development. If a man is bound by necessity to chase pleasure at the expense of the good, what sort of shape will he want you to be in? How will he train you, if he is in charge? You will see that what he wants is someone who is soft, not muscular, and not trained in full sunlight but in dappled shade someone who has never worked out like a man, never touched hard, sweaty exercise. Instead, he goes for a boy who has known only a soft unmanly style of life, who makes himself pretty with cosmetics because he has no natural color at all. There is no point in going on with this description: it is perfectly obvious what other sorts of behaviour follow from this. We can take up our next topic after drawing all this to a head: the sort of body a lover wants in his boy is one that will give confidence to the enemy in a war or other great crisis while causing alarm to friends and even to his lovers. Enough of that; the point is obvious. “Our next topic is the benefit or harm to your possessions that will come from a lover’s care and company. Everyone knows the answer, especially a lover: His first wish will be for a boy who has lost his dearest, kindliest and godliest possessions—his mother and father and other close relatives. He would be happy to see the boy deprived of them, since he would expect them either to block him from the sweet pleasure of the boy’s company or to criticize him severely for taking it. What is more, a lover would think any money or other wealth the boy owns would only make him harder to snare and, once snared, harder to handle. It follows by absolute necessity that wealth in a boyfriend will cause his lover to envy him, while his poverty will be a delight. Furthermore, he will wish for the boy to stay wifeless, childless, and homeless for as long as possible, since that’s how long he desires to go on plucking his sweet fruit. “There are other troubles in life, of course, but some divinity has mixed most of them with a dash of immediate pleasure. A flatterer, for example, may be an awful beast and a dreadful nuisance, but nature makes flattery rather pleasant by mixing in a little culture with its words. So it is with a mistress—for all the harm we accuse her of causing—and with many other creatures of that character, and their callings: at least they are delightful company for a day. But besides being harmful to his boyfriend, a lover is simply disgusting to spend the day with. ‘Youth delights youth,’ as the old proverb runs—because, I suppose, friendship grows from similarity, as boys of the same age go after the same pleasures. But you can even have too much of people your own age. Besides, as they say, it is miserable for anyone to be forced into anything by necessity—and this (to say nothing of the age difference) is most true for a boy with his lover. The older man clings to the younger day and night, never willing to leave him, driven by necessity and goaded on by the sting that gives him pleasure every time he sees, hears, touches, or perceives his boy in any way at all, so that he follows him around like a servant, with pleasure. “As for the boy, however, what comfort or pleasure will the lover give to him during all the time they spend together? Won’t it be disgusting in the extreme to see the face of that older man who’s lost his looks? And everything that goes with that face—why, it is a misery even to hear them mentioned, let alone actually handle them, as you would constantly be forced to do! To be watched and guarded suspiciously all the time, with everyone! To hear praise of yourself that is out of place and excessive! And then to be falsely accused—which is unbearable when the man is sober and not only unbearable but positively shameful when he is drunk and lays into you with a pack of wild barefaced insults! “While he is still in love he is harmful and disgusting, but after his love fades he breaks his trust with you for the future, in spite of all the promises he has made with all those oaths and entreaties which just barely kept you in a relationship that was troublesome at the time, in hope of future benefits. So, then, by the time he should pay up, he has made a change and installed a new ruling government in himself: right-minded reason in place of the madness of love. The boy does not even realize that his lover is a different man. He insists on his reward for past favors and reminds him of what they had done and said before—as if he were still talking to the same man! The lover, however, is so ashamed that he does not dare tell the boy how much he has changed or that there is no way, now that he is in his right mind and under control again, that he can stand by the promises he had sworn to uphold when he was under that old mindless regime. He is afraid that if he acted as he had before he would turn out the same and revert to his old self. So now he is a refugee, fleeing from those old promises on which he must default by necessity; he, the former lover, has to switch roles and flee, since the coin has fallen the other way, while the boy must chase after him, angry and cursing. All along he has been completely unaware that he should never have given his favors to a man who was in love—and who therefore had by necessity lost his mind. He should much rather have done it for a man who was not in love and had his wits about him. Otherwise it follows necessarily that he’d be giving himself to a man who is deceitful, irritable, jealous, disgusting, harmful to his property, harmful to his physical fitness, and absolutely devastating to the cultivation of his soul, which truly is, and will always be, the most valuable thing to gods and men. “These are the points you should bear in mind, my boy. You should know that the friendship of a lover arises without any good will at all. No, like food, its purpose is to sate hunger. ‘Do wolves love lambs? That’s how lovers befriend a boy!’” That’s it, Phaedrus. You won’t hear another word from me, and you’ll have to accept this as the end of the speech. PHAEDRUS: But I thought you were right in the middle—I thought you were about to speak at the same length about the non-lover, to list his good points and argue that it’s better to give one’s favors to him. So why are you stopping now, Socrates? SOCRATES: Didn’t you notice, my friend, that even though I am criticizing the lover, I have passed beyond lyric into epic poetry?[6] What do you suppose will happen to me if I begin to praise his opposite? Don’t you realize that the Nymphs to whom you so cleverly exposed me will take complete possession of me? So I say instead, in a word, that every shortcoming for which we blamed the lover has its contrary advantage, and the non-lover possesses it. Why make a long speech of it? That’s enough about them both. This way my story will meet the end it deserves, and I will cross the river and leave before you make me do something even worse. PHAEDRUS: Not yet, Socrates, not until this heat is over. Don’t you see that it is almost exactly noon, “straight-up” as they say? Let’s wait and discuss the speeches, and go as soon as it turns cooler. SOCRATES: You’re really superhuman when it comes to speeches, Phaedrus; you’re truly amazing. I’m sure you’ve brought into being more of the speeches that have been given during your lifetime than anyone else, whether you composed them yourself or in one way or another forced others to make them; with the single exception of Simmias the Theban, you are far ahead of the rest.[7] Even as we speak, I think, you’re managing to cause me to produce yet another one. PHAEDRUS: Oh, how wonderful! But what do you mean? What speech?  SOCRATES: My friend, just as I was about to cross the river, the familiar divine sign came to me which, whenever it occurs, holds me back from something I am about to do. I thought I heard a voice coming from this very spot, forbidding me to leave until I made atonement for some offense against the gods. In effect, you see, I am a seer, and though I am not particularly good at it, still—like people who are just barely able to read and write—I am good enough for myown purposes. I recognizemy offense clearly now. In fact, the soul too, my friend, is itself a sort of seer; that’s why, almost from the beginning of my speech, I was disturbed by a very uneasy feeling, as Ibycus puts it, that “for offending the gods I am honoured by men.”[8] But now I understand exactly what my offense has been. PHAEDRUS: Tell me, what is it? SOCRATES: Phaedrus, that speech you carried with you here—it was horrible, as horrible as the speech you made me give. PHAEDRUS: How could that be? SOCRATES: It was foolish, and close to being impious. What could be more horrible than that? PHAEDRUS: Nothing—if, of course, what you say is right. SOCRATES: Well, then? Don’t you believe that Love is the son of Aphrodite? Isn’t he one of the gods? PHAEDRUS: This is certainly what people say. SOCRATES: Well, Lysias certainly doesn’t and neither does your speech, which you charmed me through your potion into delivering myself. But if Love is a god or something divine which he is—he can’t be bad in any way; and yet our speeches just now spoke of him as if he were. That is their offense against Love. And they’ve compounded it with their utter foolishness in parading their dangerous falsehoods and preening themselves over perhaps deceiving a few silly people and coming to be admired by them. And so, my friend, I must purify myself. Now for those whose offense lies in telling false stories about matters divine, there is an ancient rite of purification—Homer did not know it, but Stesichorus did. When he lost his sight for speaking ill of Helen, he did not, like Homer, remain in the dark about the reason why. On the contrary, true follower of the Muses that he was, he understood it and immediately composed these lines: There’s no truth to that story: And as soon as he completed the poem we call the Palinode, he immediately regained his sight. Now I will prove to be wiser than Homer and Stesichorus to this small extent: I will try to offer my Palinode to Love before I am punished for speaking ill of him—with my head bare, no longer covered in shame. PHAEDRUS: No words could be sweeter to my ears, Socrates. SOCRATES: You see, my dear Phaedrus, you understand how shameless the speeches were, my own as well as the one in your book. Suppose a noble and gentle man, who was (or had once been) in love with a boy of similar character, were to hear us say that lovers start serious quarrels for trivial reasons and that, jealous of their beloved, they do him harm—don’t you think that man would think we had been brought up among the most vulgar of sailors, totally ignorant of love among the freeborn? Wouldn’t he most certainly refuse to acknowledge the flaws we attributed to Love? PHAEDRUS: Most probably, Socrates. SOCRATES: Well, that man makes me feel ashamed, and as I’m also afraid of Love himself, I want to wash out the bitterness of what we’ve heard with a more tasteful speech. And my advice to Lysias, too, is to write as soon as possible a speech urging one to give similar favors to a lover rather than to a non-lover. PHAEDRUS: You can be sure he will. For once you have spoken in praise of the lover, I will most definitely make Lysias write a speech on the same topic. SOCRATES: I do believe you will, so long as you are who you are. PHAEDRUS: Speak on, then, in full confidence. SOCRATES: Where, then, is the boy to whom I was speaking? Let him hear this speech, too. Otherwise he may be too quick to give his favors to the non-lover. PHAEDRUS: He is here, always right by your side, whenever you want him. SOCRATES: You’ll have to understand, beautiful boy, that the previous speech was by Phaedrus, Pythocles’ son, from Myrrhinus, while the one I am about to deliver is by Stesichorus, Euphemus’ son, from Himera.[10] And here is how the speech should go: “‘There’s no truth to that story’—that when a lover is available you should give your favors to a man who doesn’t love you instead, because he is in control of himself while the lover has lost his head. That would have been fine to say if madness were bad, pure and simple; but in fact the best things we have come from madness, when it is given as a gift of the god. |

ΣΩΚΡΑΤΗΣ: Ἦν οὕτω δὴ παῖς, μᾶλλον δὲ μειρακίσκος, μάλα καλός· τούτῳ δὲ ἦσαν ἐρασταὶ πάνυ πολλοί. εἷς δέ τις αὐτῶν αἱμύλος ἦν, ὃς οὐδενὸς ἧττον ἐρῶν ἐπεπείκει τὸν παῖδα ὡς οὐκ ἐρῴη· καὶ ποτε αὐτὸν αἰτῶν ἔπειθε τοῦτ᾿ αὐτό, ὡς μὴ ἐρῶντι πρὸ τοῦ ἐρῶντος δέοι χαρίζεσθαι, ἔλεγέν τε ὧδε· Περὶ παντός, ὦ παῖ, μία ἀρχὴ τοῖς μέλλουσι καλῶς [c] βουλεύεσθαι· εἰδέναι δεῖ περὶ οὗ ἂν ᾖ ἡ βουλή, ἢ παντὸς ἁμαρτάνειν ἀνάγκη. τοὺς δὲ πολλοὺς λέληθεν ὅτι οὐκ ἴσασι τὴν οὐσίαν ἑκάστου. ὡς οὖν εἰδότες οὐ διομολογοῦνται ἐν ἀρχῇ τῆς σκέψεως, προελθόντες δὲ τὸ εἰκὸς ἀποδιδόασιν· οὔτε γὰρ ἑαυτοῖς οὔτε ἀλλήλοις ὁμολογοῦσιν. ἐγὼ οὖν καὶ σὺ μὴ πάθωμεν ὃ ἄλλοις ἐπιτιμῶμεν, ἀλλ᾿ ἐπειδὴ σοὶ καὶ ἐμοὶ ὁ λόγος πρόκειται, ἐρῶντι ἢ μὴ μᾶλλον εἰς φιλίαν ἰτέον, περὶ ἔρωτος, οἷόν τ᾿ ἔστι καὶ ἣν ἔχει δύναμιν, [d] ὁμολογίᾳ θέμενοι ὅρον, εἰς τοῦτο ἀποβλέποντες καὶ ἀναφέροντες τὴν σκέψιν ποιώμεθα, εἴτε ὠφελίαν εἴτε βλάβην παρέχει. ὅτι μὲν οὖν δὴ ἐπιθυμία τις ὁ ἔρως, ἅπαντι δῆλον· ὅτι δ᾿ αὖ καὶ μὴ ἐρῶντες ἐπιθυμοῦσι τῶν καλῶν, ἴσμεν. τῷ δὴ τὸν ἐρῶντά τε καὶ μὴ κρινοῦμεν; δεῖ δὴ νοῆσαι, ὅτι ἡμῶν ἐν ἑκάστῳ δύο τινέ ἐστον ἰδέα ἄρχοντε καὶ ἄγοντε, οἷν ἑπόμεθα ᾗ ἂν ἄγητον, ἡ μὲν ἔμφυτος οὖσα ἐπιθυμία ἡδονῶν, ἄλλη δὲ ἐπίκτητος δόξα, ἐφιεμένη τοῦ ἀρίστου. τούτω δὲ ἐν ἡμῖν τοτὲ μὲν ὁμονοεῖτον, [e] ἔστι δὲ ὅτε στασιάζετον· καὶ τοτὲ μὲν ἡ ἑτέρα, ἄλλοτε δὲ ἡ ἑτέρα κρατεῖ. δόξης μὲν οὖν ἐπὶ τὸ ἄριστον λόγῳ ἀγούσης καὶ κρατούσης τῷ κράτει σωφροσύνη ὄνομα· [238a] ἐπιθυμίας δὲ ἀλόγως ἑλκούσης ἐπὶ ἡδονὰς καὶ ἀρξάσης ἐν ἡμῖν τῇ ἀρχῇ ὕβρις ἐπωνομάσθη. ὕβρις δὲ δὴ πολυώνυμον· πολυμελὲς γὰρ καὶ πολυειδές. καὶ τούτων τῶν ἰδεῶν ἐκπρεπὴς ἣ ἂν τύχῃ γενομένη, τὴν αὑτῆς ἐπωνυμίαν ὀνομαζόμενον τὸν ἔχοντα παρέχεται, οὔτε τινὰ καλὴν οὔτε ἐπαξίαν κεκτῆσθαι. περὶ μὲν γὰρ ἐδωδὴν κρατοῦσα τοῦ λόγου τοῦ ἀρίστου καὶ τῶν ἄλλων ἐπιθυμιῶν ἐπιθυμία [b] γαστριμαργία τε καὶ τὸν ἔχοντα ταὐτὸν τοῦτο κεκλημένον παρέξεται· περὶ δ᾿ αὖ μέθας τυραννεύσασα, τὸν κεκτημένον ταύτῃ ἄγουσα, δῆλον οὗ τεύξεται προσρήματος· καὶ τἆλλα δὴ τὰ τούτων ἀδελφὰ καὶ ἀδελφῶν ἐπιθυμιῶν ὀνόματα τῆς ἀεὶ δυναστευούσης ᾗ προσήκει καλεῖσθαι πρόδηλον. ἧς δ᾿ ἕνεκα πάντα τὰ πρόσθεν εἴρηται, σχεδὸν μὲν ἤδη φανερόν, λεχθὲν δὲ ἢ μὴ λεχθὲν πᾶν πως σαφέστερον· ἡ γὰρ ἄνευ λόγου δόξης ἐπὶ τὸ ὀρθὸν ὁρμώσης κρατήσασα ἐπιθυμία [c] πρὸς ἡδονὴν ἀχθεῖσα κάλλους, καὶ ὑπὸ αὖ τῶν ἑαυτῆς συγγενῶν ἐπιθυμιῶν ἐπὶ σωμάτων κάλλος ἐρρωμένως ῥωσθεῖσα νικήσασα ἀγωγή, ἀπ᾿ αὐτῆς τῆς ῥώμης ἐπωνυμίαν λαβοῦσα, ἔρως ἐκλήθη.  Ἀτάρ, ὦ φίλε Φαῖδρε, δοκῶ τι σοί, ὥσπερ ἐμαυτῷ, θεῖον πάθος πεπονθέναι; ΦΑΙΔΡΟΣ: Πάνυ μὲν οὖν, ὦ Σώκρατες, παρὰ τὸ εἰωθὸς εὔροιά τίς σε εἴληφεν. ΣΩΚΡΑΤΗΣ: Σιγῇ τοίνυν μου ἄκουε· τῷ ὄντι γὰρ θεῖος ἔοικεν [d] ὁ τόπος εἶναι· ὥστε ἐὰν ἄρα πολλάκις νυμφόληπτος προϊόντος τοῦ λόγου γένωμαι, μὴ θαυμάσῃς· τὰ νῦν γὰρ οὐκέτι πόρρω διθυράμβων φθέγγομαι. ΦΑΙΔΡΟΣ: Ἀληθέστατα λέγεις. ΣΩΚΡΑΤΗΣ: Τούτων μέντοι σὺ αἴτιος· ἀλλὰ τὰ λοιπὰ ἄκουε· ἴσως γὰρ κἂν ἀποτράποιτο τὸ ἐπιόν. ταῦτα μὲν οὖν θεῷ μελήσει, ἡμῖν δὲ πρὸς τὸν παῖδα πάλιν τῷ λόγῳ ἰτέον. Εἶεν, ὦ φέριστε· ὃ μὲν δὴ τυγχάνει ὂν περὶ οὗ βουλευτέον, εἴρηταί τε καὶ ὥρισται, βλέποντες δὲ δὴ πρὸς αὐτὸ [e] τὰ λοιπὰ λέγωμεν, τίς ὠφελία ἢ βλάβη ἀπό τε ἐρῶντος καὶ μὴ τῷ χαριζομένῳ ἐξ εἰκότος συμβήσεται. Τῷ δὴ ὑπὸ ἐπιθυμίας ἀρχομένῳ δουλεύοντί τε ἡδονῇ ἀνάγκη που τὸν ἐρώμενον ὡς ἥδιστον ἑαυτῷ παρασκευάζειν· νοσοῦντι δὲ πᾶν ἡδὺ τὸ μὴ ἀντιτεῖνον, κρεῖττον δὲ καὶ ἴσον ἐχθρόν. [239a] οὔτε δὴ κρείττω οὔτε ἰσούμενον ἑκὼν ἐραστὴς παιδικὰ ἀνέξεται, ἥττω δὲ καὶ ὑποδεέστερον ἀεὶ ἀπεργάζεται· ἥττων δὲ ἀμαθὴς σοφοῦ, δειλὸς ἀνδρείου, ἀδύνατος εἰπεῖν ῥητορικοῦ, βραδὺς ἀγχίνου. τοσούτων κακῶν καὶ ἔτι πλειόνων κατὰ τὴν διάνοιαν ἐραστὴν ἐρωμένῳ ἀνάγκη γιγνομένων τε καὶ φύσει ἐνόντων, τῶν μὲν ἥδεσθαι, τὰ δὲ παρασκευάζειν, ἢ στέρεσθαι τοῦ παραυτίκα ἡδέος. φθονερὸν δὴ ἀνάγκη [b] εἶναι, καὶ πολλῶν μὲν ἄλλων συνουσιῶν ἀπείργοντα καὶ ὠφελίμων, ὅθεν ἂν μάλιστ᾿ ἀνὴρ γίγνοιτο, μεγάλης αἴτιον εἶναι βλάβης, μεγίστης δὲ τῆς ὅθεν ἂν φρονιμώτατος εἴη. τοῦτο δὲ ἡ θεία φιλοσοφία τυγχάνει ὄν, ἧς ἐραστὴν παιδικὰ ἀνάγκη πόρρωθεν εἴργειν, περίφοβον ὄντα τοῦ καταφρονηθῆναι· τά τε ἄλλα μηχανᾶσθαι, ὅπως ἂν ᾖ πάντα ἀγνοῶν καὶ πάντα ἀποβλέπων εἰς τὸν ἐραστήν, οἷος ὢν τῷ μὲν ἥδιστος, ἑαυτῷ δὲ βλαβερώτατος ἂν εἴη. τὰ μὲν oὖν κατὰ [c] διάνοιαν ἐπίτροπός τε καὶ κοινωνὸς οὐδαμῇ λυσιτελὴς ἀνὴρ ἔχων ἔρωτα. Τὴν δὲ τοῦ σώματος ἕξιν τε καὶ θεραπείαν οἵαν τε καὶ ὡς θεραπεύσει οὗ ἂν γένηται κύριος, ὃς ἡδὺ πρὸ ἀγαθοῦ ἠνάγκασται διώκειν, δεῖ μετὰ ταῦτα ἰδεῖν. ὀφθήσεται δὲ1 μαλθακόν τινα καὶ οὐ στερεὸν διώκων, οὐδ᾿ ἐν ἡλίῳ καθαρῷ τεθραμμένον ἀλλ᾿ ὑπὸ συμμιγεῖ σκιᾷ, πόνων μὲν ἀνδρείων καὶ ἱδρώτων ξηρῶν ἄπειρον, ἔμπειρον δὲ ἁπαλῆς καὶ ἀνάνδρου [d] διαίτης, ἀλλοτρίοις χρώμασι καὶ κόσμοις χήτει οἰκείων κοσμούμενον, ὅσα τε ἄλλα τούτοις ἕπεται πάντα ἐπιτηδεύοντα, ἃ δῆλα καὶ οὐκ ἄξιον περαιτέρω προβαίνειν, ἀλλ᾿ ἓν κεφάλαιον ὁρισαμένους ἐπ᾿ ἄλλο ἰέναι· τὸ γὰρ τοιοῦτον σῶμα ἐν πολέμῳ τε καὶ ἄλλαις χρείαις ὅσαι μεγάλαι οἱ μὲν ἐχθροὶ θαρροῦσιν, οἱ δὲ φίλοι καὶ αὐτοὶ οἱ ἐρασταὶ φοβοῦνται. Τοῦτο μὲν οὖν ὡς δῆλον ἐατέον, τὸ δ᾿ ἐφεξῆς ῥητέον, [e] τίνα ἡμῖν ὠφελίαν ἢ τίνα βλάβην περὶ τὴν κτῆσιν ἡ τοῦ ἐρῶντος ὁμιλία τε καὶ ἐπιτροπεία παρέξεται. σαφὲς δὴ τοῦτό γε παντὶ μέν, μάλιστα δὲ τῷ ἐραστῇ, ὅτι τῶν φιλτάτων τε καὶ εὐνουστάτων καὶ θειοτάτων κτημάτων ὀρφανὸν πρὸ παντὸς εὔξαιτ᾿ ἂν εἶναι τὸν ἐρώμενον· πατρὸς γὰρ καὶ μητρὸς καὶ ξυγγενῶν καὶ φίλων στέρεσθαι ἂν αὐτὸν δέξαιτο, [240a] διακωλυτὰς καὶ ἐπιτιμητὰς ἡγούμενος τῆς ἡδίστης πρὸς αὐτὸν ὁμιλίας. ἀλλὰ μὴν οὐσίαν γ᾿ ἔχοντα χρυσοῦ ἤ τινος ἄλλης κτήσεως οὔτ᾿ εὐάλωτον ὁμοίως οὔτε ἁλόντα εὐμεταχείριστον ἡγήσεται· ἐξ ὧν πᾶσα ἀνάγκη ἐραστὴν παιδικοῖς φθονεῖν μὲν οὐσίαν κεκτημένοις, ἀπολλυμένης δὲ χαίρειν. ἔτι τοίνυν ἄγαμον, ἄπαιδα, ἄοικον ὅ τι πλεῖστον χρόνον παιδικὰ ἐραστὴς εὔξαιτ᾿ ἂν γενέσθαι, τὸ αὑτοῦ γλυκὺ ὡς πλεῖστον χρόνον καρποῦσθαι ἐπιθυμῶν. Ἔστι μὲν δὴ καὶ ἄλλα κακά, ἀλλά τις δαίμων ἔμιξε τοῖς [b] πλείστοις ἐν τῷ παραυτίκα ἡδονήν, οἷον κόλακι, δεινῷ θηρίῳ καὶ βλάβῃ μεγάλῃ, ὅμως ἐπέμιξεν ἡ φύσις ἡδονήν τινα οὐκ ἄμουσον, καί τις ἑταίραν ὡς βλαβερὸν ψέξειεν ἄν, καὶ ἄλλα πολλὰ τῶν τοιουτοτρόπων θρεμμάτων τε καὶ ἐπιτηδευμάτων, οἷς τό γε καθ᾿ ἡμέραν ἡδίστοισιν εἶναι ὑπάρχει· παιδικοῖς δὲ ἐραστὴς πρὸς τῷ βλαβερῷ καὶ εἰς τὸ συνημερεύειν πάντων [c] ἀηδέστατον. ἥλικα γὰρ καὶ ὁ παλαιὸς λόγος τέρπειν τὸν ἥλικα· ἡ γάρ, οἶμαι, χρόνου ἰσότης ἐπ᾿ ἴσας ἡδονὰς ἄγουσα δι᾿ ὁμοιότητα φιλίαν παρέχεται· ἀλλ᾿ ὅμως κόρον γε καὶ ἡ τούτων συνουσία ἔχει. καὶ μὴν τό γε ἀναγκαῖον αὖ βαρὺ παντὶ περὶ πᾶν λέγεται· ὃ δὴ πρὸς τῇ ἀνομοιότητι μάλιστα ἐραστὴς πρὸς παιδικὰ ἔχει. νεωτέρῳ γὰρ πρεσβύτερος συνὼν οὔθ᾿ ἡμέρας οὔτε νυκτὸς ἑκὼν ἀπολείπεται, ἀλλ᾿ ὑπ᾿ [d] ἀνάγκης τε καὶ οἴστρου ἐλαύνεται, ὃς ἐκείνῳ μὲν ἡδονὰς ἀεὶ διδοὺς ἄγει ὁρῶντι, ἀκούοντι, ἁπτομένῳ, καὶ πᾶσαν αἴσθησιν αἰσθανομένῳ τοῦ ἐρωμένου, ὥστε μεθ᾿ ἡδονῆς ἀραρότως αὐτῷ ὑπηρετεῖν· τῷ δὲ δὴ ἐρωμένῳ ποῖον παραμύθιον ἢ τίνας ἡδονὰς διδοὺς ποιήσει τὸν ἴσον χρόνον συνόντα μὴ οὐχὶ ἐπ᾿ ἔσχατον ἐλθεῖν ἀηδίας; ὁρῶντι μὲν ὄψιν πρεσβυτέραν καὶ οὐκ ἐν ὥρᾳ, ἑπομένων δὲ τῶν ἄλλων ταύτῃ, ἃ καὶ λογῳ [e] ἐστὶν ἀκούειν οὐκ ἐπιτερπές, μὴ ὅτι δὴ ἔργῳ ἀνάγκης ἀεὶ προσκειμένης μεταχειρίζεσθαι· φυλακάς τε δὴ καχυποτόπους φυλαττομένῳ διὰ παντὸς καὶ πρὸς ἅπαντας, ἀκαίρους τε καὶ ἐπαίνους καὶ ὑπερβάλλοντας ἀκούοντι, ὡς δ᾿ αὕτως ψόγους νήφοντος μὲν οὐκ ἀνεκτούς, εἰς δὲ μέθην ἰόντος πρὸς τῷ μὴ ἀνεκτῷ ἐπαισχεῖς παρρησίᾳ κατακορεῖ καὶ ἀναπεπταμένῃ χρωμένου. Καὶ ἐρῶν μὲν βλαβερός τε καὶ ἀηδής, λήξας δὲ τοῦ ἔρωτος εἰς τὸν ἔπειτα χρόνον ἄπιστος, εἰς ὃν πολλὰ καὶ μετὰ πολλῶν ὅρκων τε καὶ δεήσεων ὑπισχνούμενος μόγις [241a] κατεῖχε τὴν ἐν τῷ τότε ξυνουσίαν ἐπίπονον φέρειν δι᾿ ἐλπίδα ἀγαθῶν. τότε δὴ δέον ἐκτίνειν, μεταβαλὼν ἄλλον ἄρχοντα ἐν αὑτῷ καὶ προστάτην, νοῦν καὶ σωφροσύνην ἀντ᾿ ἔρωτος καὶ μανίας, ἄλλος γεγονὼς λέληθεν τὰ παιδικά. καὶ ὁ μὲν αὐτὸν χάριν ἀπαιτεῖ τῶν τότε, ὑπομιμνῄσκων τὰ πραχθέντα καὶ λεχθέντα, ὡς τῷ αὐτῷ διαλεγόμενος· ὁ δὲ ὑπ᾿ αἰσχύνης οὔτε εἰπεῖν τολμᾷ ὅτι ἄλλος γέγονεν, οὔθ᾿ ὅπως τὰ τῆς προτέρας ἀνοήτου ἀρχῆς ὁρκωμόσιά τε καὶ ὑποσχέσεις [b] ἐμπεδώσει ἔχει, νοῦν ἤδη ἐσχηκὼς καὶ σεσωφρονηκώς, ἵνα μὴ πράττων ταὐτὰ τῷ πρόσθεν ὅμοιός τε ἐκείνῳ καὶ ὁ αὐτὸς πάλιν γένηται. φυγὰς δὴ γίγνεται ἐκ τούτων, καὶ ἀπεστερηκὼς ὑπ᾿ ἀνάγκης ὁ πρὶν ἐραστής, ὀστράκου μεταπεσόντος, ἵεται φυγῇ μεταβαλών· ὁ δὲ ἀναγκάζεται διώκειν ἀγανακτῶν καὶ ἐπιθεάζων, ἠγνοηκὼς τὸ ἅπαν ἐξ ἀρχῆς, ὅτι οὐκ ἄρα ἔδει ποτὲ ἐρῶντι καὶ ὑπ᾿ ἀνάγκης ἀνοήτῳ χαρίζεσθαι, [c] ἀλλὰ πολὺ μᾶλλον μὴ ἐρῶντι καὶ νοῦν ἔχοντι· εἰ δὲ μή, ἀναγκαῖον εἴη ἐνδοῦναι αὑτὸν ἀπίστῳ, δυσκόλῳ, φθονερῷ, ἀηδεῖ, βλαβερῷ μὲν πρὸς οὐσίαν, βλαβερῷ δὲ πρὸς τὴν τοῦ σώματος ἕξιν, πολὺ δὲ βλαβερωτάτῳ πρὸς τὴν τῆς ψυχῆς παίδευσιν, ἧς οὔτε ἀνθρώποις οὔτε θεοῖς τῇ ἀληθείᾳ τιμιώτερον οὔτε ἔστιν οὔτε ποτὲ ἔσται. ταῦτά τε οὖν χρή, ὦ παῖ, ξυννοεῖν, καὶ εἰδέναι τὴν ἐραστοῦ φιλίαν, ὅτι οὐ μετ᾿ εὐνοίας γίγνεται, ἀλλὰ σιτίου τρόπον, χάριν πλησμονῆς, [d] ὡς λύκοι ἄρν ἀγαπῶσ᾿, ὣς παῖδα φιλοῦσιν ἐρασταί. Τοῦτ᾿ ἐκεῖνο, ὦ Φαῖδρε. οὐκέτ᾿ ἂν τὸ πέρα ἀκούσαις ἐμοῦ λέγοντος, ἀλλ᾿ ἤδη σοι τέλος ἐχέτω ὁ λόγος. ΦΑΙΔΡΟΣ: Καίτοι ᾤμην γε μεσοῦν αὐτόν, καὶ ἐρεῖν τὰ ἴσα περὶ τοῦ μὴ ἐρῶντος, ὡς δεῖ ἐκείνῳ χαρίζεσθαι μᾶλλον, λέγων2 ὅσ᾿ αὖ ἔχει ἀγαθά· νῦν δὲ δή, ὦ Σώκρατες, τί ἀποπαύει; [e] ΣΩΚΡΑΤΗΣ: Οὐκ ᾔσθου, ὦ μακάριε, ὅτι ἤδη ἔπη φθέγγομαι, ἀλλ᾿ οὐκέτι διθυράμβους, καὶ ταῦτα ψέγων; ἐὰν δ᾿ ἐπαινεῖν τὸν ἕτερον ἄρξωμαι, τί με οἴει ποιήσειν; ἆρ᾿ οἶσθ᾿ ὅτι ὑπὸ τῶν Νυμφῶν, αἷς με σὺ προὔβαλες ἐκ προνοίας, σαφῶς ἐνθουσιάσω; λέγω οὖν ἑνὶ λόγῳ, ὅτι ὅσα τὸν ἕτερον λελοιδορήκαμεν, τῷ ἑτέρῳ τἀναντία τούτων ἀγαθὰ πρόσεστι. καὶ τί δεῖ μακροῦ λόγου; περὶ γὰρ ἀμφοῖν ἱκανῶς εἴρηται. καὶ οὕτω δὴ ὁ μῦθος, ὅ τι πάσχειν προσήκει αὐτῷ, τοῦτο [242a] πείσεται· κἀγὼ τὸν ποταμὸν τοῦτον διαβὰς ἀπέρχομαι, πρὶν ὑπὸ σοῦ τι μεῖζον ἀναγκασθῆναι. ΦΑΙΔΡΟΣ: Μήπω γε, ὦ Σώκρατες, πρὶν ἂν τὸ καῦμα παρέλθῃ· ἢ οὐχ ὁρᾷς ὡς σχεδὸν ἤδη μεσημβρία ἵσταται; ἀλλὰ περιμείναντες, καὶ ἅμα περὶ τῶν εἰρημένων διαλεχθέντες, τάχα ἐπειδὰν ἀποψυχῇ ἴμεν. ΣΩΚΡΑΤΗΣ: Θεῖός γ᾿ εἶ περὶ τοὺς λόγους, ὦ Φαῖδρε, καὶ ἀτεχνῶς θαυμάσιος. οἶμαι γὰρ ἐγὼ τῶν ἐπὶ τοῦ σοῦ βίου γεγονότων [242b] μηδένα πλείους ἢ σὲ πεποιηκέναι γεγενῆσθαι ἤτοι αὐτὸν λέγοντα ἢ ἄλλους ἑνί γέ τῳ τρόπῳ προσαναγκάζοντα. Σιμμίαν Θηβαῖον ἐξαιρῶ λόγου· τῶν δὲ ἄλλων πάμπολυ κρατεῖς· καὶ νῦν αὖ δοκεῖς αἴτιός μοι γεγενῆσθαι λόγῳ τινὶ ῥηθῆναι. ΦΑΙΔΡΟΣ: Οὐ πόλεμόν γε ἀγγέλλεις· ἀλλὰ πῶς δὴ καὶ τίνι τούτῳ; ΣΩΚΡΑΤΗΣ: Ἡνίκ᾿ ἔμελλον, ὦ ᾿γαθέ, τὸν ποταμὸν διαβαίνειν, τὸ δαιμόνιόν τε καὶ τὸ εἰωθὸς σημεῖόν μοι γίγνεσθαι ἐγένετο—[c] ἀεὶ δέ με ἐπίσχει, ὃ ἂν μέλλω πράττειν—καί τινα φωνὴν ἔδοξα αὐτόθεν ἀκοῦσαι, ἥ με οὐκ ἐᾷ ἀπιέναι πρὶν ἂν ἀφοσιώσωμαι, ὥς τι ἡμαρτηκότα εἰς τὸ θεῖον. εἰμὶ δὴ οὖν μάντις μέν, οὐ πάνυ δὲ σπουδαῖος, ἀλλ᾿ ὥσπερ οἱ τὰ γράμματα φαῦλοι, ὅσον μὲν ἐμαυτῷ μόνον ἱκανός· σαφῶς οὖν ἤδη μανθάνω τὸ ἁμάρτημα. ὡς δή τοι, ὦ ἑταῖρε, μαντικόν γέ τι καὶ ἡ ψυχή· ἐμὲ γὰρ ἔθραξε μέν τι καὶ πάλαι λέγοντα τὸν λόγον, καί πως ἐδυσωπούμην κατ᾿ Ἴβυκον, μή τι παρὰ θεοῖς [d] ἀμβλακὼν τιμὰν πρὸς ἀνθρώπων ἀμείψω· νῦν δ᾿ ᾔσθημαι τὸ ἁμάρτημα. ΦΑΙΔΡΟΣ:Λέγεις δὲ δὴ τί; ΣΩΚΡΑΤΗΣ:Δεινόν, ὦ Φαῖδρε, δεινὸν λόγον αὐτός τε ἐκόμισας ἐμέ τε ἠνάγκασας εἰπεῖν. ΦΑΙΔΡΟΣ: Πῶς δή; ΣΩΚΡΑΤΗΣ: Εὐήθη καὶ ὑπό τι ἀσεβῆ· οὗ τίς ἂν εἴη δεινότερος; ΦΑΙΔΡΟΣ: Οὐδείς, εἴ γε σὺ ἀληθῆ λέγεις. ΣΩΚΡΑΤΗΣ: Τί οὖν; τὸν Ἔρωτα οὐκ Ἀφροδίτης καὶ θεόν τινα ἡγεῖ; ΦΑΙΔΡΟΣ: Λέγεταί γε δή. ΣΩΚΡΑΤΗΣ: Οὔ τι ὑπό γε Λυσίου, οὐδὲ ὑπὸ τοῦ Eσοῦ λόγου, ὃς [e] διὰ τοῦ ἐμοῦ στόματος καταφαρμακευθέντος ὑπὸ σοῦ ἐλέχθη. εἰ δ᾿ ἔστιν, ὥσπερ οὖν ἔστι, θεὸς ἤ τι θεῖον ὁ Ἔρως, οὐδὲν ἂν κακὸν εἴη· τὼ δὲ λόγω τὼ νῦν δὴ περὶ αὐτοῦ εἰπέτην ὡς τοιούτου ὄντος. ταύτῃ τε οὖν ἡμαρτανέτην περὶ τὸν Ἔρωτα, ἔτι τε ἡ εὐήθεια αὐτοῖν πάνυ ἀστεία, τὸ μηδὲν ὑγιὲς λέγοντε [243a] μηδὲ ἀληθὲς σεμνύνεσθαι ὡς τὶ ὄντε, εἰ ἄρα ἀνθρωπίσκους τινὰς ἐξαπατήσαντε εὐδοκιμήσετον ἐν αὐτοῖς. ἐμοὶ μὲν οὖν, ὦ φίλε, καθήρασθαι ἀνάγκη· ἔστι δὲ τοῖς ἁμαρτάνουσι περὶ μυθολογίαν καθαρμὸς ἀρχαῖος, ὃν Ὅμηρος μὲν οὐκ ᾔσθετο, Στησίχορος δέ. τῶν γὰρ ὀμμάτων στερηθεὶς διὰ τὴν Ἑλένης κακηγορίαν οὐκ ἠγνόησεν ὥσπερ Ὅμηρος, ἀλλ᾿ ἅτε μουσικὸς ὢν ἔγνω τὴν αἰτίαν, καὶ ποιεῖ εὐθὺς οὐκ ἔστ᾿ ἔτυμος λόγος οὗτος, οὐδ᾿ ἔβας ἐν νηυσὶν εὐσέλμοις, [b] οὐδ᾿ ἵκεο Πέργαμα Τροίας· καὶ ποιήσας δὴ πᾶσαν τὴν καλουμένην παλινῳδίαν παραχρῆμα ἀνέβλεψεν. ἐγὼ οὖν σοφώτερος ἐκείνων γενήσομαι κατ᾿ αὐτό γε τοῦτο· πρὶν γάρ τι παθεῖν διὰ τὴν τοῦ Ἔρωτος κακηγορίαν πειράσομαι αὐτῷ ἀποδοῦναι τὴν παλινῳδίαν, γυμνῇ τῇ κεφαλῇ, καὶ οὐχ ὥσπερ τότε ὑπ᾿ αἰσχύνης ἐγκεκαλυμμένος. ΦΑΙΔΡΟΣ: Τουτωνί, ὦ Σώκρατες, οὐκ ἔστιν ἅττ᾿ ἂν ἐμοὶ εἶπες ἡδίω. [c] ΣΩΚΡΑΤΗΣ: Καὶ γάρ, ὦ ᾿γαθὲ Φαῖδρε, ἐννοεῖς ὡς ἀναιδῶς εἴρησθον τὼ λόγω, οὗτός τε καὶ ὁ ἐκ τοῦ βιβλίου ῥηθείς. εἰ γὰρ ἀκούων τις τύχοι ἡμῶν γεννάδας καὶ πρᾶος τὸ ἦθος, ἑτέρου δὲ τοιούτου ἐρῶν ἢ καὶ πρότερόν ποτε ἐρασθείς, λεγόντων ὡς διὰ σμικρὰ μεγάλας ἔχθρας οἱ ἐρασταὶ ἀναιροῦνται καὶ ἔχουσι πρὸς τὰ παιδικὰ φθονερῶς τε καὶ βλαβερῶς, πῶς οὐκ ἂν οἴει αὐτὸν ἡγεῖσθαι ἀκούειν ἐν ναύταις που τεθραμμένων καὶ οὐδένα ἐλεύθερον ἔρωτα ἑωρακότων, πολλοῦ δ᾿ ἂν δεῖν [d] ἡμῖν ὁμολογεῖν ἃ ψέγομεν τὸν Ἔρωτα; ΦΑΙΔΡΟΣ: Ἴσως νὴ Δί᾿, ὦ Σώκρατες. ΣΩΚΡΑΤΗΣ: Τοῦτόν γε τοίνυν ἔγωγε αἰσχυνόμενος, καὶ αὐτὸν τὸν Ἔρωτα δεδιώς, ἐπιθυμῶ ποτίμῳ λόγῳ οἷον ἁλμυρὰν ἀκοὴν ἀποκλύσασθαι· συμβουλεύω δὲ καὶ Λυσίᾳ ὅ τι τάχιστα γράψαι, ὡς χρὴ ἐραστῇ μᾶλλον ἢ μὴ ἐρῶντι ἐκ τῶν ὁμοίων χαρίζεσθαι. ΦΑΙΔΡΟΣ: Ἀλλ᾿ εὖ ἴσθι ὅτι ἕξει τοῦθ᾿ οὕτω· σοῦ γὰρ εἰπόντος τὸν τοῦ ἐραστοῦ ἔπαινον, πᾶσα ἀνάγκη Λυσίαν ὑπ᾿ ἐμοῦ [e] ἀναγκασθῆναι γράψαι αὖ περὶ τοῦ αὐτοῦ λόγον. ΣΩΚΡΑΤΗΣ: Τοῦτο μὲν πιστεύω, ἕωσπερ ἂν ᾖς ὃς εἶ. ΦΑΙΔΡΟΣ: Λέγε τοίνυν θαρρῶν. ΣΩΚΡΑΤΗΣ: Ποῦ δή μοι ὁ παῖς πρὸς ὃν ἔλεγον; ἵνα καὶ τοῦτο ἀκούσῃ, καὶ μὴ ἀνήκοος ὢν φθάσῃ χαρισάμενος τῷ μὴ ἐρῶντι. ΦΑΙΔΡΟΣ: Οὗτος παρά σοι μάλα πλησίον ἀεὶ πάρεστιν, ὅταν σὺ βούλῃ.  ΣΩΚΡΑΤΗΣ: Οὑτωσὶ τοίνυν, ὦ παῖ καλέ, ἐννόησον, ὡς ὁ μὲν [244a] πρότερος ἦν λόγος Φαίδρου τοῦ Πυθοκλέους, Μυρρινουσίου ἀνδρός· ὃν δὲ μέλλω λέγειν, Στησιχόρου τοῦ Εὐφήμου, Ἱμεραίου. λεκτέος δὲ ὧδε, ὅτι οὐκ ἔστ᾿ ἔτυμος λόγος, ὃς ἂν παρόντος ἐραστοῦ τῷ μὴ ἐρῶντι μᾶλλον φῇ δεῖν χαρίζεσθαι, διότι δὴ ὁ μὲν μαίνεται, ὁ δὲ σωφρονεῖ. εἰ μὲν γὰρ ἦν ἁπλοῦν τὸ μανίαν κακὸν εἶναι, καλῶς ἂν ἐλέγετο· νῦν δὲ τὰ μέγιστα τῶν ἀγαθῶν ἡμῖν γίγνεται διὰ μανίας, θείᾳ μέντοι δόσει διδομένης. |

Socrates gives many examples of the benefits of divinely-inspired madness (244b-245a), then continues:

245b-c

|

SOCRATES: “There you have some of the fine achievements—and I could tell you even more—that are due to god-sent madness. We must not have any fear on this particular point, then, and we must not let anyone disturb us or frighten us with the claim that you should prefer a friend who is in control of himself to one who is disturbed. Besides proving that point, if he is to win his case, our opponent must show that love is not sent by the gods as a benefit to a lover and his boy. And we, for our part, must prove the opposite, that this sort of madness is given us by the gods to ensure our greatest good fortune. It will be a proof that convinces the wise if not the clever. “Now we must first understand the truth about the nature of the soul, divine or human, by examining what it does and what is done to it. |

ΣΩΚΡΑΤΗΣ: Τοσαῦτα μέντοι καὶ ἔτι πλείω ἔχω μανίας γιγνομένης ἀπὸ θεῶν λέγειν καλὰ ἔργα· ὥστε τοῦτό γε αὐτὸ μὴ φοβώμεθα, μηδέ τις ἡμᾶς λόγος θορυβείτω δεδιττόμενος, ὡς πρὸ τοῦ κεκινημένου τὸν σώφρονα δεῖ προαιρεῖσθαι φίλον· ἀλλὰ τόδε πρὸς ἐκείνῳ δείξας φερέσθω τὰ νικητήρια, ὡς οὐκ ἐπ᾿ ὠφελίᾳ ὁ ἔρως τῷ ἐρῶντι καὶ τῷ ἐρωμένῳ ἐκ θεῶν ἐπιπέμπεται. ἡμῖν δὲ ἀποδεικτέον αὖ τοὐναντίον, ὡς ἐπ᾿ εὐτυχίᾳ τῇ μεγίστῃ [c] παρὰ θεῶν ἡ τοιαύτη μανία δίδοται· ἡ δὲ δὴ ἀπόδειξις ἔσται δεινοῖς μὲν ἄπιστος, σοφοῖς δὲ πιστή δεῖ οὖν πρῶτον ψυχῆς φύσεως πέρι θείας τε καὶ ἀνθρωπίνης ἰδόντα πάθη τε καὶ ἔργα τἀληθὲς νοῆσαι· |

Socrates then briefly proves the immortality of the soul which belongs to every self-moving being. The soul in every mortal is a team made up of a charioteer, one good horse and one bad horse. Souls come to earth and take on earthly bodies when they shed their wings. Long afterwards, they return to heaven with wings that have regrown, nourished by wisdom and goodness at a speed determined by what they have seen and remembered of the truth they once glimpsed beyond the rim of heaven: “the soul that has seen the most shall enter into the birth of a man who is to be a philosopher or a lover of beauty, or one of a musical or loving nature”souls are likely to return faster (245c-249d). He continues:

249d-257b

|

SOCRATES: “Now this takes me to the whole point of my discussion of the fourth kind of madness—that which someone shows when he sees the beauty we have down here and is reminded of true beauty; then he takes wing and flutters in his eagerness to rise up, but is unable to do so; and he gazes aloft, like a bird, paying no attention to what is down below—and that is what brings on him the charge that he has gone mad. This is the best and noblest of all the forms that possession by god can take for anyone who has it or is connected to it, and when someone who loves beautiful boys is touched by this madness he is called a lover. As I said, nature requires that the soul of every human being has seen reality; otherwise, no soul could have entered this sort of living thing. But not every soul is easily reminded of the reality there by what it finds here—not souls that got only a brief glance at the reality there, not souls who had such bad luck when they fell down here that they were twisted by bad company into lives of injustice so that they forgot the sacred objects they had seen before. Only a few remain whose memory is good enough; and they are startled when they see an image of what they saw up there. Then they are beside themselves, and their experience is beyond their comprehension because they cannot fully grasp what it is that they are seeing. “Justice and self-control do not shine out through their images down here, and neither do the other objects of the soul’s admiration; the senses are so murky that only a few people are able to make out, with difficulty, the original of the likenesses they encounter here. But beauty was radiant to see at that time when the souls, along with the glorious chorus (we[11] were with Zeus, while others followed other gods), saw that blessed and spectacular vision and were ushered into the mystery that we may rightly call the most blessed of all. And we who celebrated it were wholly perfect and free of all the troubles that awaited us in time to come, and we gazed in rapture at sacred revealed objects that were perfect, and simple, and unshakeable and blissful. That was the ultimate vision, and we saw it in pure light because we were pure ourselves, not buried in this thing we are carrying around now, which we call a body, locked in it like an oyster in its shell. “Well, all that was for love of a memory that made me stretch out my speech in longing for the past. Now beauty, as I said, was radiant among the other objects; and now that we have come down here we grasp it sparkling through the clearest of our senses. Vision, of course, is the sharpest of our bodily senses, although it does not see wisdom. It would awaken a terribly powerful love if an image of wisdom came through our sight as clearly as beauty does, and the same goes for the other objects of inspired love. But now beauty alone has this privilege, to be the most clearly visible and the most loved. Of course a man who was initiated long ago or who has become defiled is not to be moved abruptly from here to a vision of Beauty itself when he sees what we call beauty here; so instead of gazing at the latter reverently, he surrenders to pleasure and sets out in the manner of a four-footed beast, eager to make babies; and, wallowing in vice, he goes after unnatural pleasure too, without a trace of fear or shame. A recent initiate, however, one who has seen much in heaven—when he sees a godlike face or bodily form that has captured Beauty well, first he shudders and a fear comes over him like those he felt at the earlier time; then he gazes at him with the reverence due a god, and if he weren’t afraid people would think him completely mad, he’d even sacrifice to his boy as if he were the image of a god. Once he has looked at him, his chill gives way to sweating and a high fever, because the stream of beauty that pours into him through his eyes warms him up and waters the growth of his wings. Meanwhile, the heat warms him and melts the places where the wings once grew, places that were long ago closed off with hard scabs to keep the sprouts from coming back; but as nourishment flows in, the feather shafts swell and rush to grow from their roots beneath every part of the soul (long ago, you see, the entire soul had wings). Now the whole soul seethes and throbs in this condition. Like a child whose teeth are just starting to grow in, and its gums are all aching and itching—that is exactly how the soul feels when it begins to grow wings. It swells up and aches and tingles as it grows them. But when it looks upon the beauty of the boy and takes in the stream of particles flowing into it from his beauty (that is why this is called ‘desire’[12]), when it is watered and warmed by this, then all its pain subsides and is replaced by joy. When, however, it is separated from the boy and runs dry, then the openings of the passages in which the feathers grow are dried shut and keep the wings from sprouting. Then the stump of each feather is blocked in its desire and it throbs like a pulsing artery while the feather pricks at its passageway, with the result that the whole soul is stung all around, and the pain simply drives it wild—but then, when it remembers the boy in his beauty, it recovers its joy. From the outlandish mix of these two feelings—pain and joy—comes anguish and helpless raving: in its madness the lover’s soul cannot sleep at night or stay put by day; it rushes, yearning, wherever it expects to see the person who has that beauty. When it does see him, it opens the sluice-gates of desire and sets free the parts that were blocked up before. And now that the pain and the goading have stopped, it can catch its breath and once more suck in, for the moment, this sweetest of all pleasures. This it is not at all willing to give up, and no one is more important to it than the beautiful boy. It forgets mother and brothers and friends entirely and doesn’t care at all if it loses its wealth through neglect. And as for proper and decorous behavior, in which it used to take pride, the soul despises the whole business. Why, it is even willing to sleep like a slave, anywhere, as near to the object of its longing as it is allowed to get! That is because in addition to its reverence for one who has such beauty, the soul has discovered that the boy is the only doctor for all that terrible pain.  “This is the experience we humans call love, you beautiful boy (I mean the one to whom I am making this speech).[13] You are so young that what the gods call it is likely to strike you as funny. Some of the successors of Homer, I believe, report two lines from the less well known poems, of which the second is quite indecent and does not scan very well. They praise love this way: Yes, mortals call him powerful winged ‘Love’; You may believe this or not as you like. But, seriously, the cause of love is as I have said, and this is how lovers really feel. “If the man who is taken by love used to be an attendant on Zeus, he will be able to bear the burden of this feathered force with dignity. But if it is one of Ares’ troops who has fallen prisoner of love—if that is the god with whom he took the circuit—then if he has the slightest suspicion that the boy he loves has done him wrong, he turns murderous, and he is ready to make a sacrifice of himself as well as the boy. “So it is with each of the gods: everyone spends his life honoring the god in whose chorus he danced, and emulates that god in every way he can, so long as he remains undefiled and in his first life down here. And that is how he behaves with everyone at every turn, not just with those he loves. Everyone chooses his love after his own fashion from among those who are beautiful, and then treats the boy like his very own god, building him up and adorning him as an image to honor and worship. Those who followed Zeus, for example, choose someone to love who is a Zeus himself in the nobility of his soul. So they make sure he has a talent for philosophy and the guidance of others, and once they have found him and are in love with him they do everything to develop that talent. If any lovers have not yet embarked on this practice, then they start to learn, using any source they can and also making progress on their own. They are well equipped to track down their god’s true nature with their own resources because of their driving need to gaze at the god, and as they are in touch with the god by memory they are inspired by him and adopt his customs and practices, so far as a human being can share a god’s life. For all of this they know they have the boy to thank, and so they love him all the more; and if they draw their inspiration from Zeus, then, like the Bacchants,[15] they pour it into the soul of the one they love in order to help him take on as much of their own god’s qualities as possible. Hera’s followers look for a kingly character, and once they have found him they do all the same things for him. And so it is for followers of Apollo or any other god: They take their god’s path and seek for their own a boy whose nature is like the god’s; and when they have got him they emulate the god, convincing the boy they love and training him to follow their god’s pattern and way of life, so far as is possible in each case. They show no envy, no mean-spirited lack of generosity, toward the boy, but make every possible effort to draw him into being totally like themselves and the god to whom they are devoted. This, then, is any true lover’s heart’s desire: if he follows that desire in the manner I described, this friend who has been driven mad by love will secure a consummation for the one he has befriended that is as beautiful and blissful as I said—if, of course, he captures him. Here, then, is how the captive is caught: “Remember how we divided each soul in three at the beginning of our story—two parts in the form of horses and the third in that of a charioteer? Let us continue with that. One of the horses, we said, is good, the other not; but we did not go into the details of the goodness of the good horse or the badness of the bad. Let us do that now. The horse that is on the right, or nobler, side is upright in frame and well jointed, with a high neck and a regal nose; his coat is white, his eyes are black, and he is a lover of honor with modesty and self-control; companion to true glory, he needs no whip, and is guided by verbal commands alone. The other horse is a crooked great jumble of limbs with a short bull-neck, a pug nose, black skin, and bloodshot white eyes; companion to wild boasts and indecency, he is shaggy around the ears—deaf as a post—and just barely yields to horsewhip and goad combined. Now when the charioteer looks in the eye of love, his entire soul is suffused with a sense of warmth and starts to fill with tingles and the goading of desire. As for the horses, the one who is obedient to the charioteer is still controlled, then as always, by its sense of shame, and so prevents itself from jumping on the boy. The other one, however, no longer responds to the whip or the goad of the charioteer; it leaps violently forward and does everything to aggravate its yokemate and its charioteer, trying to make them go up to the boy and suggest to him the pleasures of sex. At first the other two resist, angry in their belief that they are being made to do things that are dreadfully wrong. At last, however, when they see no end to their trouble, they are led forward, reluctantly agreeing to do as they have been told. So they are close to him now, and they are struck by the boy’s face as if by a bolt of lightning. When the charioteer sees that face, his memory is carried back to the real nature of Beauty, and he sees it again where it stands on the sacred pedestal next to Self-control. At the sight he is frightened, falls over backwards awestruck, and at the same time has to pull the reins back so fiercely that both horses are set on their haunches, one falling back voluntarily with no resistance, but the other insolent and quite unwilling. They pull back a little further; and while one horse drenches the whole soul with sweat out of shame and awe, the other—once it has recovered from the pain caused by the bit and its fall—bursts into a torrent of insults as soon as it has caught its breath, accusing its charioteer and yokemate of all sorts of cowardice and unmanliness for abandoning their position and their agreement. Now once more it tries to make its unwilling partners advance, and gives in grudgingly only when they beg it to wait till later. Then, when the promised time arrives, and they are pretending to have forgotten, it reminds them; it struggles, it neighs, it pulls them forward and forces them to approach the boy again with the same proposition; and as soon as they are near, it drops its head, straightens its tail, bites the bit, and pulls without any shame at all. The charioteer is now struck with the same e feelings as before, only worse, and he’s falling back as he would from a starting gate; and he violently yanks the bit back out of the teeth of the insolent horse, only harder this time, so that he bloodies its foul speaking tongue and jaws, sets its legs and haunches firmly on the ground, and ‘gives it over to pain.’[16] When the bad horse has suffered this same thing time after time, it stops being so insolent; now it is humble enough to follow the charioteer’s warnings, and when it sees the beautiful boy it dies of fright, with the result that now at last the lover’s soul follows its boy in reverence and awe. “And because he is served with all the attentions due a god by a lover who is not pretending otherwise but is truly in the throes of love, and because he is by nature disposed to be a friend of the man who is serving him (even if he has already been set against love by schoolfriends or others who say that it is shameful to associate with a lover, and initially rejects the lover in consequence), as time goes forward he is brought by his ripening age and a sense of what must be to a point where he lets the man spend time with him. It is a decree of fate, you see, that bad is never friends with bad, while good cannot fail to be friends with good. Now that he allows his lover to talk and spend time with him, and the man’s good will is close at hand, the boy is amazed by it as he realizes that all the friendship he has from his other friends and relatives put together is nothing compared to that of this friend who is inspired by a god. “After the lover has spent some time doing this, staying near the boy (and even touching him during sports and on other occasions), then the spring that feeds the stream Zeus named ‘Desire’ when he was in love with Ganymede begins to flow mightily in the lover and is partly absorbed by him, and when he is filled it overflows and runs away outside him. Think how a breeze or an echo bounces back from a smooth solid object to its source; that is how the stream of beauty goes back to the beautiful boy and sets him aflutter. It enters through his eyes, which are its natural route to the soul; there it waters the passages for the wings, starts the wings growing, and fills the soul of the loved one with love in return. Then the boy is in love, but has no idea what he loves. He does not understand, and cannot explain, what has happened to him. It is as if he had caught an eye disease from someone else, but could not identify the cause; he does not realize that he is seeing himself in the lover as in a mirror. So when the lover is near, the boy’s pain is relieved just as the lover’s is, and when they are apart he yearns as much as he is yearned for, because he has a mirror image of love in him—‘backlove’—though he neither speaks nor thinks of it as love, but as friendship. Still, his desire is nearly the same as the lover’s, though weaker: he wants to see, touch, kiss, and lie down with him; and of course, as you might expect, he acts on these desires soon after they occur. “When they are in bed, the lover’s undisciplined horse has a word to say to the charioteer—that after all its sufferings it is entitled to a little fun. Meanwhile, the boy’s bad horse has nothing to say, but swelling with desire, confused, it hugs the lover and kisses him in delight at his great good will. And whenever they are lying together it is completely unable, for its own part, to deny the lover any favor he might beg to have. Its yokemate, however, along with its charioteer, resists such requests with modesty and reason. Now if the victory goes to the better elements in both their minds, which lead them to follow the assigned regimen of philosophy, their life here below is one of bliss and shared understanding. They are modest and fully in control of themselves now that they have enslaved the part that brought trouble into the soul and set free the part that gave it virtue. After death, when they have grown wings and become weightless, they have won the first of three rounds in these, the true Olympic Contests. There is no greater good than this that either human self-control or divine madness can offer a man. If, on the other hand, they adopt a lower way of living, with ambition in place of philosophy, then pretty soon when they are careless because they have been drinking or for some other reason, the pair’s undisciplined horses will catch their souls off guard and together bring them to commit that act which ordinary people would take to be the happiest choice of all; and when they have consummated it once, they go on doing this for the rest of their lives, but sparingly, since they have not approved of what they are doing with their whole minds. So these two also live in mutual friendship (though weaker than that of the philosophical pair), both while they are in love and after they have passed beyond it, because they realize they have exchanged such firm vows that it would be forbidden for them ever to break them and become enemies. In death they are wingless when they leave the body, but their wings are bursting to sprout, so the prize they have won from the madness of love is considerable, because those who have begun the sacred journey in lower heaven may not by law be sent into darkness for the journey under the earth; their lives are bright and happy as they travel together, and thanks to their love they will grow wings together when the time comes. “These are the rewards you will have from a lover’s friendship, my boy, and they are as great as divine gifts should be. A non-lover’s companionship, on the other hand, is diluted by human self control; all it pays are cheap, human dividends, and though the slavish attitude it engenders in a friend’s soul is widely praised as virtue, it tosses the soul around for nine thousand years on the earth and leads it, mindless, beneath it. “So now, dear Love, this is the best and most beautiful palinode[17] we could offer as payment for our debt, especially in view of the rather poetical choice of words Phaedrus made me use.[18] Forgive us our earlier speeches in return for this one; be kind and gracious toward my expertise at love, which is your own gift to me: do not, out of anger, take it away or disable it; and grant that I may be held in higher esteem than ever by those who are beautiful. If Phaedrus and I said anything that shocked you in our earlier speech, blame it on Lysias, who was its father, and put a stop to his making speeches of this sort; convert him to philosophy like his brother Polemarchus so that his lover here may no longer play both sides as he does now, but simply devote his life to Love through philosophical discussions.” |