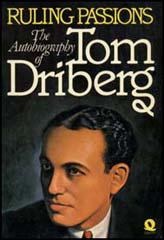

RULING PASSIONS

BY TOM DRIBERG

Thomas Edward Neil Driberg (22 May 1905 – 12 August 1976), created Baron Bradwell in 1975, was a radical Labour Member of Parliament, author and possible spy. His unfinished memoir, Ruling Passions: An Autobiography, written when dying, was published by Jonathan Cape in London in 1977. Presented here is all its Greek love content.

2 Piety and puberty

After describing how, from the age of ten or eleven, he indulged “fairly regularly in sexual play” with other boys and had a not fully consummated love affair with a boy a year or two older than him:

By the time I was twelve, puberty was setting in. The first long, straggling pubic hair was a source of amazement to me. So were the erections, which I did not yet know what to do with. (Nor did I have any wet dreams.) Within a year I had learned: my juvenile lust was so importunate that an old tramp was induced to masturbate me in an underground lavatory at Tunbridge Wells. He did it rather roughly, with a mechanical action, and, since I did not understand what was happening, the moment of ejaculation was as agonising as it was exquisite. Throughout adolescence, during holidays from school, I used to cycle into Tunbridge Wells or Brighton and haunt the various public lavatories for hours on end, especially the one in which I had lost what I can hardly call my virtue. This gents’ convenience (in an alley just opposite a railway station) had one feature which was both a safeguard against snoopers and a spur to tumescence: there was quite a long flight of steps down to it, so that one could hear a newcomer, and guess what he was like, before seeing him. If he was quick and light of step and turned out to be a randy soldier or a rosy errand-boy— best of all, if he was ready and willing, but sometimes even if he was not—the impatient sperm would not be contained and the coming was a good deal hotter and faster than that of the Magi. During these vigils, I hardly ever failed to score, except when the prospects were scared of having so young a boy. So far as their ages went, my taste was more catholic than it later became: I found middle-aged men as exciting as boys of my own age. I have often thought how wrong it is (as also, I believe, in the case of girls) to assume that the senior partner must be the seducer. I remember an agreeable session when I was at Lancing, lying on top of the Sussex downs with a man of about fifty. At the time I was in quarantine after a bout of measles and had been allowed out for a walk from the school sanatorium: I only hope he didn’t catch anything. The pleasure was mutual: the fault, if there were one, mine. [pp. 15-6]

3 Family ties

I must wind up this melancholy chapter with some account of my two brothers, Jack Herbert and James Douglas Driberg. Having been born in 1888 and 1890, they were, as I have said, much older than I. Both were distinguished in their professions, but at crucial points in both their lives something went wrong—through their own faults or not, I cannot tell — and they suffered humiliation and even disgrace. Both were heterosexual (though I have heard that, towards the end of the Second World War, in Cairo, Jack began casting lascivious eyes on the Arab boys); both were married, both divorced, both childless (though Jack, again, once told me that he had an ‘illegitimate’ child in France). [p. 29]

4 Grace and disgrace

On Driberg’s disgrace in the autumn term of 1923, his last at the boys’ boarding-school Lancing in Sussex:

At any rate, two of the boys in my dormitory resisted my nocturnal overtures and complained of them to the housemaster. (One of them was an extremely pretty boy with fair curly hair named Hector Lorenzo Christie.[1] He lived at Jervaulx Abbey in Yorkshire; this he eventually inherited from his centenarian father, who had for some years been ‘the oldest living Old Etonian’.) This meant severe punishment, administered in the ways most calculated to make me feel ashamed of myself. [p. 51]

5 Oxford 1

On Edward James, his fellow undergraduate at Christ Church, Oxford:

When a boy at Eton, James had attracted the amorous attentions of a celebrated Liberal statesman, Sir William Harcourt. This became known to the authorities and, to avoid public scandal, Sir William shot himself on the splendid marble staircase of his town house in Brook Street, now the Savile Club.[2]

7 Down and out, and in

On his leaving Oxford in 1927:

I knew that I wanted to be a writer—I had always known this even at Lancing (where I had contributed some shaming items to the school magazine, including a poem ‘For J.’, who was E. J. (Jimmy) Watson, the boy I worshipped most despairingly and could never touch, since he was younger and in another house).[3] [p. 87]

On when Driberg had just started working as a journalist for the Express in 1928:

A job came up that would go to a junior reporter: there had been an airplane crash at the Royal Air Force College, Cranwell, and I was told to ring the Air Ministry and get any details and the names of those killed. Fortunately, only a few had been killed (fortunately for me, too, since I did not do shorthand). 'The names were read out to me, and the last name was Watson, E. J.—the boy I had been most in love with, at a distance, at Lancing.

On reflection, I don’t think poor Jimmy Watson would have made the Ideal Mate whom so many of us are vainly looking for all our lives. [p. 95] Driberg then explains that he had corresponded with Watson when he was at Oxford and received a letter from him pointedly describing his liaisons with girls.

[1] Since Christie was born on 22 August 1907, was thus more than two years younger than Driberg and was only just sixteen (as well as being thought of by Driberg as “an extremely pretty boy”), this overture could be considered pederastic. However, it should be noted in the months that intervened between the 18-year-old Driberg leaving Lancing and going up to Oxford, he taught at a prep school (schools then typically catering to boys of 7 or 8 to 12 or 13), where he found “the boys were too young for me.” (p. 55).

[2] For a much fuller account of this, including a footnote casting doubt on this explanation of Harcourt’s death, see Swans Reflecting Elephants by Edward James himself.

[3] Eric James Watson, born on 7 November 1906, was accidentally killed on 17 February 1928. As he was only a year and a half younger than Driberg, this is a debatable instance of Greek love.

Comments powered by CComment