THE TWO KINDS OF LOVE

BY LUCIAN OF SAMOSATA

The Erotes Ἔρωτες has been variously translated as Loves and Affairs of the Heart and The Two Kinds of Love, of which the first is the most literal, but fails to convey what it is about: a dialogue debating whether the love of women or of boys is better. The authorship has traditionally and generally been ascribed to the 2nd century AD Hellenised satirist Lucian of Samosata in Syria (most of whose many works were written in Athens in the last quarter of that century), though a preponderance of scholars for much of the twentieth century (only) held this ascription to be false.

It is presented here in its entirety, as all of it is of Greek love interest. The translation is by M. D. MacLeod for the Loeb Classical Library volume 432, published by William Heinemann in London in 1967, but his Latinisation of Greek names has been undone in favour of more literal transliteration.

|

LYKINOS [1] Theomnestos, my friend, since dawn your sportive talk about love has filled these ears of mine that were weary of unremitting attention to serious topics. As I was parched with thirst for relaxation of this sort, your delightful stream of merry stories was very welcome to me. For the human spirit is too weak to endure serious pursuits all the time, and ambitious toils long to gain some little respite from tiresome cares and to have freedom for the joys of life. This morning I have been quite gladdened by the sweet winning seductiveness of your wanton stories, so that I almost thought I was Aristeides being enchanted beyond measure by those Milesian Tales,[1] and I swear by those Loves of yours that have found so broad a target that I am indeed sorry that you’ve come to the end of your stories. If you think this is but idle talk on my part, I beg you in the name of Aphrodite herself, if you’ve omitted mention of any of your love affairs with a lad or even with a girl, coax it forth with the aid of memory. Besides we are celebrating a festival today and sacrificing to Herakles. You know well enough, I’m sure, how impetuous that god was where love was concerned, and so I think he’ll be most delighted to receive your stories by way of an offering. THEOMNESTOS [2] You would find it quicker, my dear Lykinos, to count me the waves of the sea or the flakes of a snowstorm than to count my loves. For I for my part think that their quiver has been left completely empty and, if they choose to fly off in quest of one more victim, their weaponless right arms will be laughed to scorn. For, almost from the time when I left off being a boy and was accounted a young man, I have been beguiled by one passion after another. One Love has ever succeeded another, and almost before I’ve ended earlier ones later Loves begin. They are veritable Lernean heads appearing in greater multiplicity than on the self-regenerating Hydra, and no Iolaos can help against them.[2] For one flame is not extinguished by another. There dwells in my eyes so nimble a gadfly that it pounces on any and every beauty as its prey and is never sated enough to stop. And I am always wondering why Aphrodite bears me this grudge. For I am no child of the Sun[3], nor am I puffed up with the insolence of the Lemnian women[4] or the boorish contempt of Hippolytos[5] that I should have provoked this unceasing wrath on the part of the goddess. |

ΛΥΚΙΝΟΣ [1] Ἐρωτικῆς παιδιᾶς, ἑταῖρέ μοι Θεόμνηστε, ἐξ ἑωθινοῦ πεπλήρωκας ἡμῶν τὰ κεκμηκότα πρὸς τὰς συνεχεῖς σπουδὰς ὦτα, καί μοι σφόδρα διψῶντι τοιαύτης ἀνέσεως εὔκαιρος ἡ τῶν ἱλαρῶν σου λόγων ἐρρύη χάρις· ἀσθενὴς γὰρ ἡ ψυχὴ διηνεκοῦς σπουδῆς ἀνέχεσθαι, ποθοῦσι δ᾿ οἱ φιλότιμοι πόνοι μικρὰ τῶν ἐπαχθῶν φροντίδων χαλασθέντες εἰς ἡδονὰς ἀνίεσθαι. πάνυ δή με ὑπὸ τὸν ὄρθρον ἡ τῶν ἀκολάστων σου διηγημάτων αἱμύλη καὶ γλυκεῖα πειθὼ κατεύφραγκεν, ὥστ᾿ ὀλίγου δεῖν Ἀριστείδης ἐνόμιζον εἶναι τοῖς Μιλησιακοῖς λόγοις ὑπερκηλούμενος, ἄχθομαί τε νὴ τοὺς σοὺς ἔρωτας, οἷς πλατὺς εὑρέθης σκοπός, ὅτι πέπαυσαι διηγούμενος· καί σε πρὸς αὐτῆς ἀντιβολοῦμεν Ἀφροδίτης, εἰ περιττά με λέγειν ἔοικας, εἴ τις ἄρρην ἢ καὶ νὴ Δία θῆλυς ἀφεῖταί4 σοι πόθος, ἠρέμα τῇ μνήμῃ ἐκκαλέσασθαι. καὶ γὰρ ἄλλως ἑορταστικὴν ἄγομεν ἡμέραν Ἡράκλεια θύοντες· οὐκ ἀγνοεῖς δὲ δήπου τὸν θεὸν ὡς ὀξὺς ἦν πρὸς Ἀφροδίτην· ἥδιστα οὖν δοκεῖ μοι τῶν λόγων τὰς θυσίας προσήσεσθαι. ΘΕΟΜΝΗΣΤΟΣ [2] Θᾶττον ἄν μοι, ὦ Λυκῖνε, θαλάττης κύματα καὶ πυκνὰς ἀπ᾿ οὐρανοῦ νιφάδας ἀριθμήσειας ἢ τοὺς ἐμοὺς Ἔρωτας. ἐγὼ γοῦν ἅπασαν αὐτῶν κενὴν ἀπολελεῖφθαι φαρέτραν νομίζω, κἂν ἐπ᾿ ἄλλον τινὰ πτῆναι θελήσωσιν, ἄνοπλος αὐτῶν ἡ δεξιὰ γελασθήσεται· σχεδὸν γὰρ ἐκ τῆς ἀντίπαιδος ἡλικίας εἰς τοὺς ἐφήβους κριθεὶς ἄλλαις ἀπ᾿ ἄλλων ἐπιθυμίαις βουκολοῦμαι· διάδοχοι ἔρωτες ἀλλήλων καὶ πρὶν ἢ λῆξαι τῶν προτέρων, ἄρχονται δεύτεροι, κάρηνα Λερναῖα τῆς παλιμφυοῦς Ὕδρας πολυπλοκώτερα μηδ᾿ Ἰόλεων βοηθὸν ἔχειν δυνάμενα· πυρὶ γὰρ οὐ σβέννυται πῦρ. οὕτως τις ὑγρὸς τοῖς ὄμμασιν ἐνοικεῖ μύωψ, ὃς ἅπαν κάλλος εἰς αὑτὸν ἁρπάζων ἐπ᾿ οὐδενὶ κόρῳ παύεται· καὶ συνεχὲς ἀπορεῖν ἐπέρχεταί μοι, τίς οὗτος Ἀφροδίτης ὁ χόλος· οὐ γὰρ Ἡλιάδης ἐγώ τις οὐδὲ Λημνιάδων ὕβρεις οὐδὲ Ἱππολύτειον ἀγροικίαν ὠφρυωμένος, ὡς ἐρεθίσαι τῆς θεοῦ τὴν ἄπαυστον ταύτην ὀργήν. |

|

LYKINOS [3] Stop this affected and unpleasant play-acting, Theomnestos. Are you really annoyed that Fortune has allotted you the life you have? Do you think it a hardship that you associate with women at their fairest and boys at the flower of their beauty? But perhaps you’ll actually need to take purges for so unpleasant an ailment. For you do suffer shockingly, I must say. Why won’t you get all this nonsense out of your system and think yourself fortunate that god has not given you for your lot squalid husbandry or the wanderings of a merchant or a soldier’s life under arms? But your interests are in the oily wrestling-schools, in resplendent clothes that shed luxury right down to your feet, and in seeing that your hair is fashionably dressed. The very torment of your amorous yearnings delights you and you find sweetness in the bite of passion’s tooth. For when you have tempted you hope, and when you have won your suit you take your pleasure, but get as much pleasure from future joys as from the present. Just now at any rate, when you were going through in Hesiodic fashion the long catalogue of your loves[6] from the beginning, the merry glances of your eyes grew meltingly liquid, and, giving your voice a delicate sweetness so that it matched that of the daughter of Lykambes,[7] you made it immediately plain from your very manner that you were in love not only with your loves but also with their memory. Come, if there is any scrap of your voyage in the seas of love that you have omitted, reveal everything, and make your sacrifice to Herakles complete and perfect. THEOMNESTOS [4] Herakles is a devourer of oxen, my dear Lykinos, and takes very little pleasure, they say, in sacrifices that have no savoury smoke. But we are honouring his annual feast with discourse. Accordingly, as my narratives have continued since dawn and lasted too long, let your Muse, departing from her customary seriousness, spend the day in merriment along with the god, and, as I can see you incline to neither type of passion, prove yourself, I beg, an impartial judge. Decide whether you consider those superior who love boys or those who delight in womankind. For I who have been smitten by both passions hang like an accurate balance with both scales in equipoise. But you, being unaffected by either, will choose the better of the two by using the impartial judgement of your reason. Away with all coyness, my dear friend, and cast now the vote entrusted to you in your capacity as judge of my loves. |

ΛΥΚΙΝΟΣ [3] Πέπαυσο τῆς ἐπιπλάστου καὶ δυσχεροῦς ταύτης ὑποκρίσεως, Θεόμνηστε. ἄχθῃ γὰρ ὅτι τούτῳ τῷ βίῳ ἡ τύχη προσεκλήρωσέν, καὶ χαλεπὸν εἶναι νομίζεις, εἰ γυναιξὶν ὡραίαις καὶ μετὰ παίδων τὸ καλὸν ἀνθούντων ὁμιλεῖς; ἀλλά σοι καὶ καθαρσίων τάχα δεήσει πρὸς τὸ δυσχερὲς οὕτω νόσημα· δεινὸν γὰρ τὸ πάθος. ἀλλ᾿ οὐχὶ τοῦτον τὸν πολὺν ἐκχέας λῆρον εὐδαίμονα σαυτὸν εἶναι νομιεῖς, ὅτι σοι ὁ θεὸς οὐκ αὐχμηρὰν γεωργίαν ἐπέκλωσεν οὐδὲ ἐμπορικὰς ἄλας καὶ στρατιώτην ἐν ὅπλοις βίον, ἀλλὰ λιπαραὶ παλαῖστραι μέλουσί σοι καὶ φαιδρὰ μὲν ἐσθὴς μέχρι ποδῶν τὴν τρυφὴν καθειμένη, διακριδὸν δ᾿ ἠσκημένης κόμης ἐπιμέλεια; τῶν γε μὴν ἐρωτικῶν ἱμέρων αὐτὸ τὸ βασανίζον εὐφραίνει καὶ γλυκὺς ὀδοὺς ὁ τοῦ πόθου δάκνει· πειράσας μὲν γὰρ ἐλπίζεις, τυχὼν δ᾿ ἀπολέλαυκας· ἴση δὲ ἡδονὴ τῷ παρεῖναι καὶ τὸ μέλλον. ἔναγχος γοῦν διηγουμένου σου τὸν πολύν, ὡς παρ᾿ Ἡσιόδῳ, κατάλογον ὧν ἀρχῆθεν ἠράσθης, ἱλαραὶ μὲν τῶν ὀμμάτων αἱ βολαὶ τακερῶς ἀνυγραίνοντο, τὴν φωνὴν δ᾿ ἴσην τῇ Λυκάμβου θυγατρὶ λεπτὸν ἀφηδύνων ἀπ᾿ αὐτοῦ τοῦ σχήματος εὐθὺς δῆλος ἦς οὐκ ἐκείνων μόνων, ἀλλὰ καὶ τῆς ἐπ᾿ αὐτοῖς μνήμης ἐρῶν. ἀλλ᾿, εἴ τί σοι τοῦ κατὰ τὴν Ἀφροδίτην περίπλου λείψανον ἀφεῖται, μηδὲν ἀποκρύψῃ, τῷ δὲ Ἡρακλεῖ τὴν θυσίαν ἐντελῆ παράσχου. ΘΕΟΜΝΗΣΤΟΣ [4] Βουφάγος μὲν ὁ δαίμων, ὦ Λυκῖνε, καὶ ταῖς ἀκάπνοις, φασί, τῶν θυσιῶν ἥκιστα τερπόμενος. ἐπεὶ δ᾿ αὐτοῦ τὴν ἐτήσιον ἑορτὴν λόγῳ γεραίρομεν, αἱ μὲν ἐμαὶ διηγήσεις ἐξ ἑωθινοῦ παραταθεῖσαι κόρον ἔχουσιν, ἡ δὲ σὴ Μοῦσα τῆς συνήθους μεθαρμοσαμένη σπουδῆς ἱλαρῶς τῷ θεῷ συνδιημερευσάτω, καί μοι γενοῦ δικαστὴς ἴσος, ἐπεὶ μηδ᾿ εἰς ἕτερόν σε τοῦ πάθους ῥέποντα ὁρῶ, ποτέρους ἀμείνονας ἡγῇ, τοὺς φιλόπαιδας ἢ τοὺς γυναίοις ἀσμενίζοντας; ἐγὼ μὲν γὰρ ὁ πληγεὶς ἑκατέρῳ καθάπερ ἀκριβὴς τρυτάνη ταῖς ἐπ᾿ ἀμφότερα πλάστιγξιν ἰσορρόπως ταλαντεύομαι, σὺ δ᾿ ἐκτὸς ὢν ἀδεκάστῳ κριτῇ τῷ λογισμῷ τὸ βέλτιον αἱρήσῃ. πάντα δὴ περιελὼν ἀκκισμόν, ὦ φιλότης, ἣν πεπίστευκέν σοι ψῆφον ἡ περὶ τῶν ἐμῶν ἐρώτων κρίσις, ἤδη φέρε. |

|

LYKINOS [5] My dear Theomnestos, do you imagine that my narratives are a matter of sport and laughter? No, they promise something serious too. I at any rate have undertaken this task on the spur of the moment, because I’ve known it to be far from a laughing matter ever since the time I heard two men arguing heatedly with each other about these two types of love, and I still have the memory of it ringing in my ears. They were opposites, not only in their arguments but in their passions, unlike you who, thanks to your easy-going spirit, go sleepless and earn double wages, “One as a herdsman of cattle, another as tender of white flocks.”[8] On the contrary, one took excessive delight in boys and thought love of women a pit of doom, while the other, virgin of all love of males, was highly susceptible to women. So I presided over a contest between these two warring passions and found the occasion quite indescribably delightful. The imprint of their words remains inscribed in my ears almost as though they had been spoken a moment ago. Therefore, putting aside all pretexts for being excused this task, I shall retail to you exactly what I heard the two of them say. THEOMNESTOS Well, I shall get up from here and sit facing you, “waiting the time when Aiakos’ son makes an end of his singing.”[9] But you must unfold for us in song the old and glorious lays of the contest of loves. LYKINOS [6] I had in mind going to Italy and a swift ship had been made ready for me. It was one of the double-banked vessels which seem particularly to be used by the Liburnians, a race who live along the Ionian Gulf. After paying such respects as I could to the local gods and invoking Zeus, God of Strangers, to assist propitiously in my expedition to foreign parts, I left the town and drove down to the sea with a pair of mules. Then I bade farewell to those who were escorting me, for I was followed by a throng of determined scholars who kept talking to me and parted with me reluctantly. Well, I climbed on to the poop and took my seat near the helmsman. We were soon carried away from land by the surge of our oars and, since we had very favourable breezes astern, we raised the mast from the hold and ran the yard up to the masthead. Then we let all our canvas down over the sheets and, as our sail gently filled, we went whistling along just as loud, I fancy, as an arrow does, and flew through the waves which roared around our prow as it cut through them. |

ΛΥΚΙΝΟΣ [5] Παιδιᾶς, ὦ Θεόμνηστε, καὶ γέλωτος ἡγῇ τὴν διήγησιν; ἡ δ᾿ ἐπαγγέλλεται καὶ σπουδαῖον. ἐγὼ γοῦν ἐξ ὑπογύου τῆς ἐπιχειρήσεως ἡψάμην, εἰδὼς ὅτι λίαν ἀλλοία παιδιᾶς ἐξότε δυοῖν ἀνδροῖν ἀκηκοὼς περὶ τούτοιν συντόνως ἁμιλλωμένοιν ἔτι τὴν μνήμην ἔναυλον ἔχω. διῄρητο δ᾿ αὐτῶν ἅμα τοῖς λόγοις τὰ πάθη καὶ οὐχ ὥσπερ σὺ κατ᾿ εὐκολίαν ψυχῆς ἄϋπνος ὢν διττοὺς ἄρνυσαι μισθούς, ΘΕΟΜΝΗΣΤΟΣ Καὶ μὴν ἔγωγε ἐπαναστὰς ἔνθεν ἀπαντικρὺ καθεδοῦμαί σου, σὺ δ᾿ ἡμῖν τὰ πάλαι κλέα τῆς ἐρωτικῆς διαφορᾶς μελῳδίᾳ περαίνειν. ΛΥΚΙΝΟΣ |

|

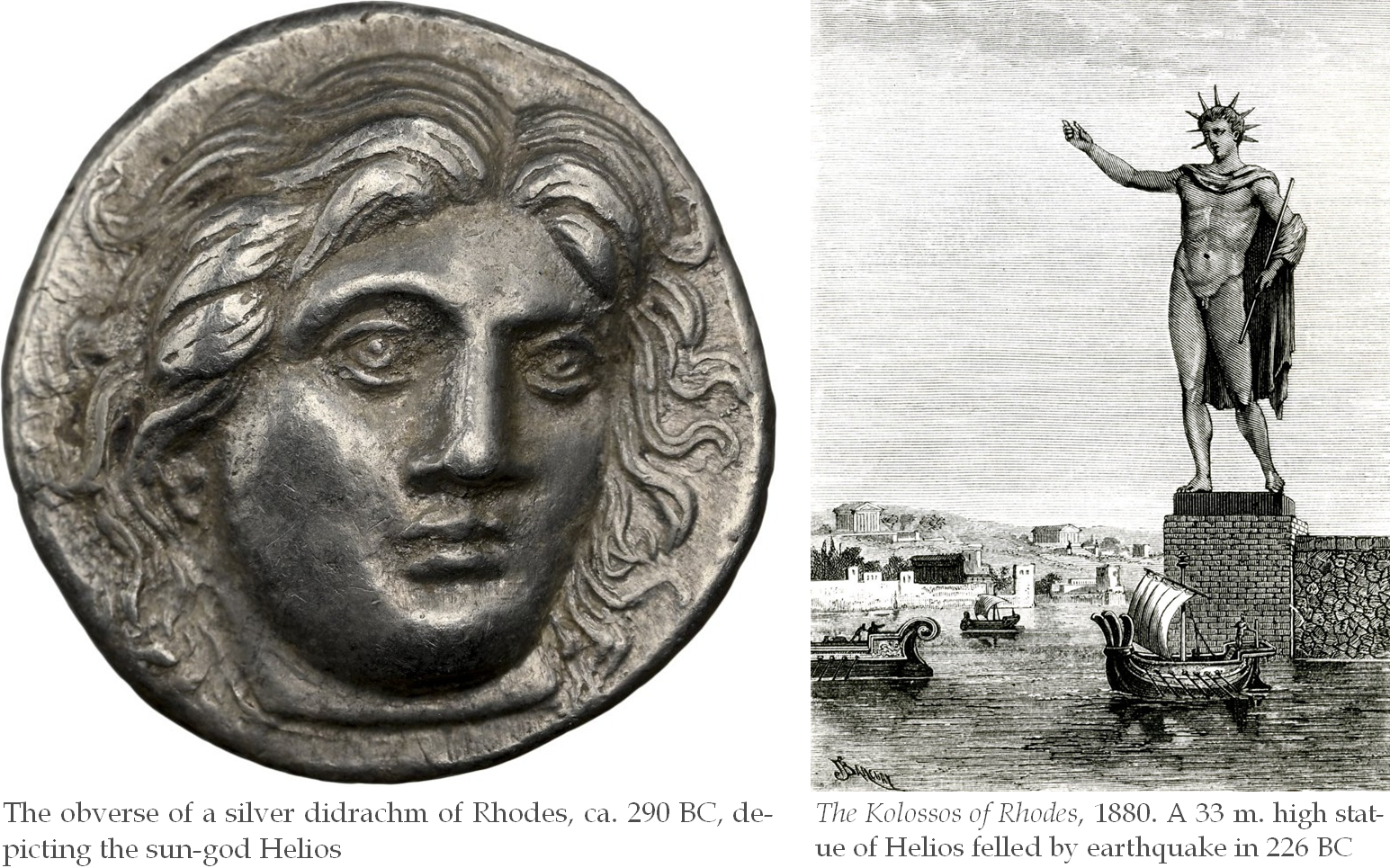

[7] But it isn’t the time to describe at any length the events serious or light of the intervening coastal voyage. But, when we had passed the Cilician seaboard and were in the gulf of Pamphylia, after passing with some difficulty the Swallow Islands, those fortune-favoured limits of ancient Greece, we visited each of the Lycian cities, where we found our chief pleasure in the tales told, for no vestige of prosperity is visible in them to the eye. Eventually we made Rhodes, the island of the Sun-God, and decided to take a short rest from our uninterrupted voyaging. [8] Accordingly our oarsmen hauled the ship ashore and pitched their tents nearby. I had been provided with accommodation opposite the temple of Dionysos, and, as I strolled along unhurriedly, I was filled with an extraordinary pleasure. For it really is the city of Helios[10] with a beauty in keeping with that god. As I walked round the porticos in the temple of Dionysos, I examined each painting, not only delighting my eyes but also renewing my acquaintance with the tales of the heroes. For immediately two or three fellows rushed up to me, offering for a small fee to explain every story for me, though most of what they said I had already guessed for myself. |

[7] ἀλλ᾿ ἅ γε μὴν ἐν τῷ μεταξὺ παράπλῳ σπουδῆς ἢ παιδιᾶς ἐχόμενα συνηνέχθη, καιρὸς οὐ πάνυ μηκύνειν. ὡς δὲ τῆς Κιλικίας τὴν ἔφαλον ἀμείψαντες εἰχόμεθα τοῦ Παμφυλίου κόλπου, Χελιδονέας ὑπερθέοντες οὐκ ἀμοχθεὶ τοὺς εὐτυχεῖς τῆς παλαιᾶς Ἑλλάδος ὅρους, ἑκάστῃ τῶν Λυκιακῶν πόλεων ἐπεξενούμεθα μύθοις τὰ πολλὰ χαίροντες· οὐδὲν γὰρ ἐν αὐταῖς σαφὲς εὐδαιμονίας ὁρᾶται λείψανον· ἄχρι τῆς Ἡλιάδος ἁψάμενοι Ῥόδου τὸ συνεχὲς τοῦ μεταξὺ πλοῦ διαναπαῦσαι πρὸς ὀλίγον ἐκρίναμεν. [8] οἱ μὲν οὖν ἐρέται τὸ σκάφος ἔξαλον ἐς γῆν ἀνασπάσαντες ἐγγὺς ἐσκήνωσαν, ἐγὼ δ᾿ εὐτρεπισμένου μοι ξενῶνος ἀπαντικρὺ τοῦ Διονυσίου κατὰ σχολὴν ἐβάδιζον ὑπερφυοῦς ἀπολαύσεως ἐμπιμπλάμενος· ἔστιν γὰρ ὄντως ἡ πόλις Ἡλίου πρέπον ἔχουσα τῷ θεῷ τὸ κάλλος. ἐκπεριϊὼν δὲ τὰς ἐν τῷ Διονυσίῳ στοὰς ἑκάστην γραφὴν κατώπτευον ἅμα τῷ τέρποντι τῆς ὄψεως ἡρωϊκοὺς μύθους ἀνανεούμενος· εὐθὺ γάρ μοι δύ᾿ ἢ τρεῖς προσερρύησαν ὀλίγου διαφόρου πᾶσαν ἱστορίαν ἀφηγούμενοι· τὰ δὲ πολλὰ καὶ αὐτὸς εἰκασίᾳ προὐλάμβανον. |

|

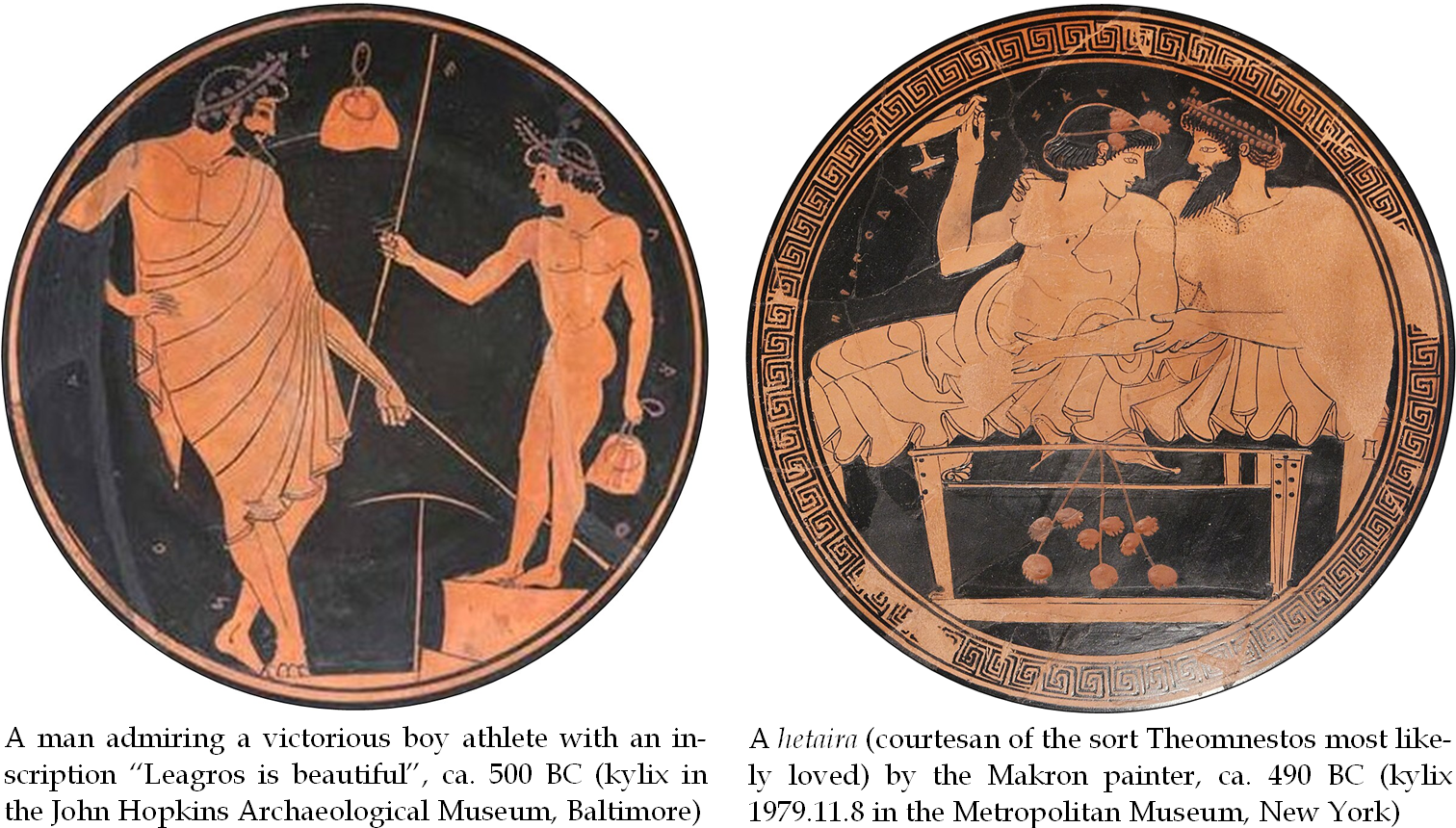

[9] When I had now had my fill of sightseeing and was minded to go to my lodgings, I met with the most delightful of all blessings in a strange land, old acquaintances of long standing, whom I think you also know yourself, for you’ve often seen them visiting us here, Charikles a young man from Corinth who is not only handsome but shows some evidence of skilful use of cosmetics, because, I imagine, he wishes to attract the women, and with him Kallikratidas, the Athenian, a man of straightforward ways. For he was pre-eminent among the leading figures in public speaking and in this forensic oratory of ours. He was also a devotee of physical training, though in my opinion he was only fond of the wrestling-schools because of his love for boys. For he was enthusiastic only for that, while his hatred for women made him often curse Prometheus.[11] Well, they both saw me from a distance and hurried up to me overjoyed and delighted. Then, as so often happens, each of them clasped me by the hand and begged me to visit his house. I, seeing that they were carrying their rivalry too far, said, “Today, Kallikratidas and Charikles, it is the proper thing for both of you to be my guests so that you may not fan your rivalry into greater flame. But on the days to follow -- for I’ve decided to remain here for three or four days -- you will return my hospitality by entertaining me each in turn, drawing lots to decide which of you will start.” [10] This was agreed, and for that day I presided as host, while on the next day Kallikratidas did so, and after him Charikles. Now, even when they were entertaining me, I could see concrete evidence of the inclinations of each. For my Athenian friend was well provided with handsome slave-boys and all of his servants were pretty well beardless. They remained with him till the down first appeared on their faces, but, once any growth cast a shadow on their cheeks, they would be sent away to be stewards and overseers of his properties at Athens. Charikles, however, had in attendance a large band of dancing girls and singing girls and all his house was as full of women as if it were the Thesmophoria[12], with not the slightest trace of male presence except that here and there could be seen an infant boy or a superannuated old cook whose age could give even the jealous no cause for suspicion. Well, these things were themselves, as I said, sufficient indications of the dispositions of both of them. Often, however, short skirmishes broke out between them without the point at issue being settled. But, when it was time for me to put to sea, at their wish I took them with me to share my voyage, for they like me were minded to set out for Italy. |

[9] ἤδη δὲ τῆς θέας ἅλις ἔχοντι καὶ διανοουμένῳ μοι βαδίζειν οἴκαδε τὸ ἥδιστον ἐπὶ ξένης ἀπήντησέ μοι κέρδος, ἄνδρες ἐκ παλαιοῦ χρόνου συνήθεις, οὓς οὐδ᾿ αὐτὸς ἀγνοεῖν μοι δοκεῖς πολλάκις ἡμῖν ἰδὼν ἐπιφοιτῶντας ἐνταῦθα, τὸν ἐκ Κορίνθου Χαρικλέα νεανίαν οὐκ ἄμορφον, ἔχοντά τι καὶ κομμωτικῆς ἀσκήσεως ἅτε οἶμαι γυναίοις ἐνωραϊζόμενον· ἅμα δ᾿ αὐτῷ καὶ Καλλικρατίδαν τὸν Ἀθηναῖον τὸν τρόπον ἁπλοϊκόν· προηγουμένως γὰρ πολιτικῶν λόγων προΐστατο καὶ ταυτησὶ τῆς ἀγοραίου ῥητορικῆς. ἦν δὲ καὶ τῷ σώματι γυμναστικός, οὐ δι᾿ ἄλλο τί μοι δοκεῖν τὰς παλαίστρας ἀγαπῶν ἢ διὰ τοὺς παιδικοὺς ἔρωτας· ὅλος γὰρ εἰς τοῦτο ἐπτόητο. τῷ δὲ πρὸς τὸ θῆλυ μίσει πολλὰ καὶ Προμηθεῖ κατηρᾶτο. πόρρωθεν οὖν ἰδὼν ἑκάτερός με γήθους καὶ χαρᾶς πλέοι προσέδραμον· εἶθ᾿ ὁποῖα φιλεῖ, δεξιωσάμενοι πρὸς αὐτὸν ἐλθεῖν ἑκάτερος ἠξίουν με. κἀγὼ φιλονεικοῦντας ὁρῶν περαιτέρω, Τὸ μὲν τήμερον, εἶπον, ὦ Καλλικρατίδα καὶ Χαρίκλεις, ἄμφω καλῶς ἔχον ἐστὶν ὑμᾶς παρ᾿ ἐμοὶ1 φοιτᾶν, ἵνα μὴ πλείω τὴν ἔριν ἐγείρητε· ταῖς δὲ ἐφεξῆς ἡμέραις—τρεῖς γὰρ ἐνταῦθα ἢ τέτταρας διέγνωκα μένειν—ἀμοιβαίως ἀνθεστιάσετέ2 με, κλήρῳ διακριθεὶς ὁ πρότερος. [10] δοκεῖ ταῦτα. κἀκείνην μὲν τὴν ἡμέραν εἱστιάρχουν ἐγώ, τῇ δ᾿ ἐπιούσῃ Καλλικρατίδας, εἶτα μετ᾿ αὐτὸν ὁ Χαρικλῆς. ἑώρων δὴ καὶ παρὰ τὴν ἑστίασιν ἐναργῆ τῆς ἑκατέρου διαθέσεως τεκμήρια· ὁ μὲν γὰρ Ἀθηναῖος εὐμόρφοις παισὶν ἐξήσκητο, καὶ πᾶς οἰκέτης αὐτῷ σχεδὸν ἀγένειος ἦν μέχρι τοῦ πρῶτον ὑπογράφοντος αὐτοὺς χνοῦ παραμένοντες, ἐπειδὰν δὲ ἰούλοις αἱ παρειαὶ πυκασθῶσιν, οἰκονόμοι καὶ τῶν Ἀθήνησι χωρίων κηδεμόνες ἀπεστέλλοντο. Χαρικλεῖ γε μὴν πολὺς ὀρχηστρίδων καὶ μουσουργῶν χορὸς εἵπετο καὶ πᾶν τὸ δωμάτιον ὡς ἐν Θεσμοφορίοις γυναικῶν μεστὸν ἦν ἀνδρὸς οὐδ᾿ ἀκαρῆ παρόντος, εἰ μή τί που νήπιον ἢ γέρων ὑπερῆλιξ ὀψοποιὸς ὀφθείη, χρόνου ζηλοτυπίας ὑποψίαν οὐκ ἔχοντος. ἦν μὲν οὖν, ὡς ἔφην, καὶ ταῦθ᾿ ἱκανὰ τῆς ἀμφοτέρων γνώμης δείγματα. πολλάκις γε μὴν ἐπ᾿ ὀλίγον ἁψιμαχίαι τινὲς αὐτοῖς ἐκινήθησαν, οὐχ ὡς πέρας ἔχειν τι τὴν ζήτησιν. ἀλλ᾿ ἐπεὶ καιρὸς ἦν ἀνάγεσθαι, σύμπλους ἐθελήσαντας αὐτοὺς ἐπηγόμην· διενοοῦντο γὰρ εἰς τὴν Ἰταλίαν ἀπαίρειν ὁμοίως ἐμοί. |

| [11] Now, as we had decided to anchor at Knidos to see the temple of Aphrodite, which is famed as possessing the most truly lovely example of Praxiteles’ skill,[13] we gently approached the land with the goddess herself, I believe, escorting our ship with smooth calm waters. The others occupied themselves with the usual preparations, but I took the two authorities on love, one on either side of me, and went round Knidos, finding no little amusement in the wanton products of the potters, for I remembered I was in Aphrodite’s city. First we went round the porticos of Sostratos and everywhere else that could give us pleasure and then we walked to the temple of Aphrodite. Charikles and I did so very eagerly, but Kallikratidas was reluctant because he was going to see something female, and would have preferred, I imagine, to have had Eros of Thespiai[14] instead of Aphrodite of Knidos. | [11] καὶ δόξαν ἡμῖν Κνίδῳ προσορμῆσαι κατὰ θέαν καὶ τοῦ Ἀφροδίτης ἱεροῦ—ὑμνεῖται δὲ τούτου τὸ τῆς Πραξιτέλους εὐχερείας ὄντως ἐπαφρόδιτον—ἠρέμα τῇ γῇ προσηνέχθημεν αὐτῆς οἶμαι τῆς θεοῦ λιπαρᾷ γαλήνῃ πομποστολούσης τὸ σκάφος. τοῖς μὲν οὖν ἄλλοις ἔμελον αἱ συνήθεις παρασκευαί, ἐγὼ δὲ τὸ ἐρωτικὸν ζεῦγος ἑκατέρωθεν ἐξαψάμενος κύκλῳ περιῄειν τὴν Κνίδον οὐκ ἀγελαστὶ τῆς κεραμευτικῆς ἀκολασίας μετέχων ὡς ἐν Ἀφροδίτης πόλει. στοὰς δὲ Σωστράτου καὶ τἆλλα ὅσα τέρπειν ἡμᾶς ἐδύνατο, πρῶτον ἐκπεριελθόντες ἐπὶ τὸν νεὼν τῆς Ἀφροδίτης βαδίζομεν, νὼ μέν, ἐγώ τε καὶ Χαρικλῆς, πάνυ προθύμως, Καλλικρατίδας δ᾿ ὡς ἐπὶ θέαν θήλειαν ἄκων, ἥδιον ἂν οἶμαι τῆς Ἀφροδίτης Κνιδίας τὸν ἐν Θεσπιαῖς ἀντικαταλλαξάμενος Ἔρωτα. |

| [12] And immediately, it seemed, there breathed upon us from the sacred precinct itself breezes fraught with love. For the uncovered court was not for the most part paved with smooth slabs of stone to form an unproductive area but, as was to be expected in Aphrodite’s temple, was all of it prolific with garden fruits. These trees, luxuriant far and wide with fresh green leaves, roofed in the air around them. But more than all others flourished the berry-laden myrtle growing luxuriantly beside its mistress[15] and all the other trees that are endowed with beauty. Though they were old in years they were not withered or faded but, still in their youthful prime, swelled with fresh sprays. Intermingled with these were trees that were unproductive except for having beauty for their fruit-cypresses and planes that towered to the heavens and with them Daphne,[16] who deserted from Aphrodite and fled from that goddess long ago. But around every tree crept and twined the ivy,[17] devotee of love. Rich vines were hung with their thick clusters of grapes. For Aphrodite is more delightful when accompanied by Dionysos and the gifts of each are sweeter if blended together, but, should they be parted from each other, they afford less pleasure. Under the particularly shady trees were joyous couches for those who wished to feast themselves there. These were occasionally visited by a few folk of breeding, but all the city rabble flocked there on holidays and paid true homage to Aphrodite. | [12] καί πως εὐθὺς ἡμῖν ἀπ᾿ αὐτοῦ τοῦ τεμένους Ἀφροδίσιοι προσέπνευσαν αὖραι· τὸ γὰρ αἴθριον οὐκ εἰς ἔδαφος ἄγονον μάλιστα λίθων πλαξὶ λείαις ἐστρωμένον, ἀλλ᾿ ὡς ἐν Ἀφροδίτης ἅπαν ἦν γόνιμον ἡμέρων καρπῶν, ἃ ταῖς κόμαις εὐθαλέσιν ἄχρι πόρρω βρύοντα τὸν πέριξ ἀέρα συνωρόφουν. περιττόν γε μὴν ἡ πυκνόκαρπος ἐτεθήλει μυρρίνη παρὰ τὴν δέσποιναν αὐτῆς δαψιλὴς πεφυκυῖα τῶν τε λοιπῶν δένδρων ἕκαστον, ὅσα κάλλους μετείληχεν· οὐδ᾿ αὐτὰ γέροντος ἤδη χρόνου πολιὰ καθαύαινεν, ἀλλ᾿ ὑπ᾿ ἀκμῆς σφριγῶντα νέοις κλωσὶν ἦν ὥρια. τούτοις δ᾿ ἀνεμέμικτο καὶ τὰ καρπῶν μὲν ἄλλως ἄγονα, τὴν δ᾿ εὐμορφίαν ἔχοντα καρπόν, κυπαρίττων γε καὶ πλατανίστων αἰθέρια μήκη καὶ σὺν αὐταῖς αὐτόμολος Ἀφροδίτης ἡ τῆς θεοῦ πάλαι φυγὰς Δάφνη. παντί γε μὴν δένδρῳ περιπλέγδην ὁ φίλερως προσείρπυζε κιττός. ἀμφιλαφεῖς ἄμπελοι πυκνοῖς κατήρτηντο βότρυσιν· τερπνοτέρα γὰρ Ἀφροδίτη μετὰ Διονύσου καὶ τὸ παρ᾿ ἀμφοῖν ἡδὺ σύγκρατον, εἰ δ᾿ ἀποζευχθεῖεν ἀλλήλων, ἧττον εὐφραίνουσιν. ἦν δ᾿ ὑπὸ ταῖς ἄγαν παλινσκίοις ὕλαις ἱλαραὶ κλισίαι τοῖς ἐνεστιᾶσθαι θέλουσιν, εἰς ἃ τῶν μὲν ἀστικῶν σπανίως ἐπεφοίτων τινές, ἀθρόος δ᾿ ὁ πολιτικὸς ὄχλος ἐπανηγύριζεν ὄντως ἀφροδισιάζοντες. |

|

[13] When the plants had given us pleasure enough, we entered the temple. In the midst thereof sits the goddess -- she’s a most beautiful statue of Parian marble -- arrogantly smiling a little as a grin parts her lips. Draped by no garment, all her beauty is uncovered and revealed, except in so far as she unobtrusively uses one hand to hide her private parts. So great was the power of the craftsman’s art that the hard unyielding marble did justice to every limb. Charikles at any rate raised a mad distracted cry and exclaimed, “Happiest indeed of the gods was Ares,[18] who suffered chains because of her!” And, as he spoke, he ran up and, stretching out his neck as far as he could, started to kiss the goddess with importunate lips. Kallikratidas stood by in silence with amazement in his heart. [14] And so we decided to see all of the goddess and went round to the back of the precinct. Then, when the door had been opened by the woman responsible for keeping the keys, we were filled with an immediate wonder for the beauty we beheld. The Athenian who had been so impassive an observer a minute before, upon inspecting those parts of the goddess which recommend a boy, suddenly raised a shout far more frenzied than that of Charikles. “Heracles!” he exclaimed, “what a well-proportioned back! What generous flanks she has! How satisfying an armful to embrace! How delicately moulded the flesh on the buttocks, neither too thin and close to the bone, nor yet revealing too great an expanse of fat! And as for those precious parts sealed in on either side by the hips, how inexpressibly sweetly they smile! How perfect the proportions of the thighs and the shins as they stretch down in a straight line to the feet! So that’s what Ganymede looks like as he pours out the nectar in heaven for Zeus and makes it taste sweeter. For I’d never have taken the cup from Hebe if she served me.” While Kallikratidas was shouting this under the spell of the goddess, Charikles in the excess of his admiration stood almost petrified, though his emotions showed in the melting tears trickling from his eyes. |

[13] ἐπεὶ δ᾿ ἱκανῶς τοῖς φυτοῖς ἐτέρφθημεν, εἴσω τοῦ νεὼ παρῄειμεν. ἡ μὲν οὖν θεὸς ἐν μέσῳ καθίδρυται—Παρίας δὲ λίθου δαίδαλμα κάλλιστον—ὑπερήφανον καὶ σεσηρότι γέλωτι μικρὸν ὑπομειδιῶσα. πᾶν δὲ τὸ κάλλος αὐτῆς ἀκάλυπτον οὐδεμιᾶς ἐσθῆτος ἀμπεχούσης γεγύμνωται, πλὴν ὅσα τῇ ἑτέρᾳ χειρὶ τὴν αἰδῶ λεληθότως ἐπικρύπτειν. τοσοῦτόν γε μὴν ἡ δημιουργὸς ἴσχυσε τέχνη, ὥστε τὴν ἀντίτυπον οὕτω καὶ καρτερὰν τοῦ λίθου φύσιν ἑκάστοις μέλεσιν ἐπιπρέπειν. ὁ γοῦν Χαρικλῆς ἐμμανές τι καὶ παράφορον ἀναβοήσας, Εὐτυχέστατος, εἶπεν, θεῶν ὁ διὰ ταύτην δεθεὶς Ἄρης, καὶ ἅμα προσδραμὼν λιπαρέσι τοῖς χείλεσιν ἐφ᾿ ὅσον ἦν δυνατὸν ἐκτείνων τὸν αὐχένα κατεφίλει· σιγῇ δ᾿ ἐφεστὼς ὁ Καλλικρατίδας κατὰ νοῦν ἀπεθαύμαζεν. ἔστι δ᾿ ἀμφίθυρος ὁ νεὼς καὶ τοῖς θέλουσι κατὰ νώτου τὴν θεὸν ἰδεῖν ἀκριβῶς, ἵνα μηδὲν αὐτῆς ἀθαύμαστον ᾖ. δι᾿ εὐμαρείας οὖν ἐστι τῇ ἑτέρᾳ πύλῃ παρελθοῦσιν τὴν ὄπισθεν εὐμορφίαν διαθρῆσαι. [14] δόξαν οὖν ὅλην τὴν θεὸν ἰδεῖν, εἰς τὸ κατόπιν τοῦ σηκοῦ περιήλθομεν. εἶτ᾿ ἀνοιγείσης τῆς θύρας ὑπὸ τοῦ κλειδοφύλακος ἐμπεπιστευμένου γυναίου θάμβος αἰφνίδιον ἡμᾶς εἶχεν τοῦ κάλλους. ὁ γοῦν Ἀθηναῖος ἡσυχῇ πρὸ μικροῦ βλέπων ἐπεὶ τὰ παιδικὰ μέρη τῆς θεοῦ κατώπτευσεν, ἀθρόως πολὺ τοῦ Χαρικλέους ἐμμανέστερον ἀνεβόησεν, Ἡράκλεις, ὅση μὲν τῶν μεταφρένων εὐρυθμία, πῶς δ᾿ ἀμφιλαφεῖς αἱ λαγόνες, ἀγκάλισμα χειροπληθές· ὡς δ᾿ εὐπερίγραφοι τῶν γλουτῶν αἱ σάρκες ἐπικυρτοῦνται μήτ᾿ ἄγαν ἐλλιπεῖς αὐτοῖς ὀστέοις προσεσταλμέναι μήτε εἰς ὑπέρογκον ἐκκεχυμέναι πιότητα. τῶν δὲ τοῖς ἰσχίοις ἐνεσφραγισμένων ἐξ ἑκατέρων τύπων οὐκ ἂν εἴποι τις ὡς ἡδὺς ὁ γέλως· μηροῦ τε καὶ κνήμης ἐπ᾿ εὐθὺ τεταμένης ἄχρι ποδὸς ἠκριβωμένοι ῥυθμοί. τοιοῦτος ἄρα Γανυμήδης ἐν οὐρανῷ Διὶ τὸ νέκταρ ἥδιον ἐγχεῖ· παρὰ μὲν γὰρ Ἥβης οὐκ ἂν ἐγὼ διακονουμένης ποτὸν ἐδεξάμην. ἐνθεαστικῶς ταῦτα τοῦ Καλλικρατίδου βοῶντος ὁ Χαρικλῆς ὑπὸ τοῦ σφόδρα θάμβους ὀλίγου δεῖν ἐπεπήγει τακερόν τι καὶ ῥέον ἐν τοῖς ὄμμασι πάθος ἀνυγραίνων. |

|

[15] When we could admire no more, we noticed a mark on one thigh like a stain on a dress; the unsightliness of this was shown up by the brightness of the marble everywhere else. I therefore, hazarding a plausible guess about the truth of the matter, supposed that what we saw was a natural defect in the marble. For even such things as these are subject to accident and many potential masterpieces of beauty are thwarted by bad luck. And so, thinking the black mark to be a natural blemish, I found in this too cause to admire Praxiteles for having hidden what was unsightly in the marble in the parts less able to be examined closely. But the attendant woman who was standing near us told us a strange, incredible story. For she said that a young man of a not undistinguished family -- though his deed has caused him to be left nameless -- who often visited the precinct, was so ill-starred as to fall in love with the goddess.[19] He would spend all day in the temple and at first gave the impression of pious awe. For in the morning he would leave his bed long before dawn to go to the temple and only return home reluctantly after sunset. All day long would he sit facing the goddess with his eyes fixed uninterruptedly upon her, whispering indistinctly and carrying on a lover’s complaints in secret conversation. [16] But when he wished to give himself some little comfort from his suffering, after first addressing the goddess, he would count out on the table four knuckle-bones of a Libyan gazelle and take a gamble on his expectations. If he made a successful throw and particularly if ever he was blessed with the throw named after the goddess herself,[20] and no dice showed the same face, he would prostrate himself before the goddess, thinking he would gain his desire. But, if as usually happens he made an indifferent throw on to his table, and the dice revealed an unpropitious result, he would curse all Knidos and show utter dejection as if at an irremediable disaster; but a minute later he would snatch up the dice and try to cure by another throw his earlier lack of success. But presently, as his passion grew more inflamed, every wall came to be inscribed with his messages and the bark of every tender tree told of fair Aphrodite. Praxiteles was honoured by him as much as Zeus and every beautiful treasure that his home guarded was offered to the goddess. In the end the violent tension of his desires turned to desperation and he found in audacity a procurer for his lusts. For, when the sun was now sinking to its setting, quietly and unnoticed by those present, he slipped in behind the door and, standing invisible in the inmost part of the chamber, he kept still, hardly even breathing. When the attendants closed the door from the outside in the normal way, this new Anchises[21] was locked in. But why do I chatter on and tell you in every detail the reckless deed of that unmentionable night? These marks of his amorous embraces were seen after day came and the goddess had that blemish to prove what she’d suffered. The youth concerned is said, according to the popular story told, to have hurled himself over a cliff or down into the waves of the sea and to have vanished utterly. |

[15] ρου μηροῦ σπίλον εἴδομεν ὥσπερ ἐν ἐσθῆτι κηλῖδα· ἤλεγχε δ᾿ αὐτοῦ τὴν ἀμορφίαν ἡ περὶ τἆλλα τῆς λίθου λαμπρότης. ἐγὼ μὲν οὖν πιθανῇ τἀληθὲς εἰκασίᾳ τοπάζων φύσιν ᾤμην τοῦ λίθου τὸ βλεπόμενον εἶναι· πάθος γὰρ οὐδὲ τούτων ἔστιν ἔξω, πολλὰ δὲ τοῖς κατ᾿ ἄκρον εἶναι δυναμένοις καλοῖς ἡ τύχη παρεμποδίζει. μέλαιναν οὖν ἐσπιλῶσθαι φυσικήν τινα κηλῖδα νομίζων καὶ κατὰ τοῦτο τοῦ Πραξιτέλους ἐθαύμαζον, ὅτι τοῦ λίθου τὸ δύσμορφον ἐν τοῖς ἧττον ἐλέγχεσθαι δυναμένοις μέρεσιν ἀπέκρυψεν. ἡ δὲ παρεστῶσα πλησίον ἡμῶν ζάκορος ἀπίστου λόγου καινὴν παρέδωκεν ἱστορίαν· ἔφη γὰρ οὐκ ἀσήμου γένους νεανίαν—ἡ δὲ πρᾶξις ἀνώνυμον αὐτὸν ἐσίγησεν—πολλάκις ἐπιφοιτῶντα τῷ τεμένει σὺν δειλαίῳ δαίμονι ἐρασθῆναι τῆς θεοῦ καὶ πανήμερον ἐν τῷ ναῷ διατρίβοντα κατ᾿ ἀρχὰς ἔχειν δεισιδαίμονος ἁγιστείας δόκησιν· ἔκ τε γὰρ τῆς ἑωθινῆς κοίτης πολὺ προλαμβάνων τὸν ὄρθρον ἐπεφοίτα καὶ μετὰ δύσιν ἄκων ἐβάδιζεν οἴκαδε τήν θ᾿ ὅλην ἡμέραν ἀπαντικρὺ τῆς θεοῦ καθεζόμενος ὀρθὰς ἐπ᾿ αὐτὴν διηνεκῶς τὰς τῶν ὀμμάτων βολὰς ἀπήρειδεν. ἄσημοι δ᾿ αὐτῷ ψιθυρισμοὶ καὶ κλεπτομένης λαλιᾶς ἐρωτικαὶ διεπεραίνοντο μέμψεις. [16] ἐπειδὰν δὲ καὶ μικρὰ τοῦ πάθους ἑαυτὸν ἀποβουκολῆσαι θελήσειεν, προσειπών, τῇ δὲ τραπέζῃ τέτταρας ἀστραγάλους Λιβυκῆς δορκὸς ἀπαριθμήσας διεπέττευε τὴν ἐλπίδα, καὶ βαλὼν μὲν ἐπίσκοπα, μάλιστα δ᾿ εἴ ποτε τὴν θεὸν αὐτὴν εὐβολήσειε, μηδενὸς ἀστραγάλου πεσόντος ἴσῳ σχήματι, προσεκύνει τῆς ἐπιθυμίας τεύξεσθαι νομίζων· εἰ δ᾿, ὁποῖα φιλεῖ, φαύλως κατὰ τῆς τραπέζης ῥίψειεν, οἱ δ᾿ ἐπὶ τὸ δυσφημότερον ἀνασταῖεν, ὅλῃ Κνίδῳ καταρώμενος ὡς ἐπ᾿ ἀνηκέστῳ συμφορᾷ [καὶ] κατήφει καὶ δι᾿ ὀλίγου συναρπάσας ἑτέρῳ βόλῳ τὴν πρὶν ἀστοχίαν ἐθεράπευεν. ἤδη δὲ πλέον αὐτῷ τοῦ πάθους ἐρεθιζομένου τοῖχος ἅπας ἐχαράσσετο καὶ πᾶς μαλακοῦ δένδρου φλοιὸς Ἀφροδίτην καλὴν ἐκήρυσσεν· ἐτιμᾶτο δ᾿ ἐξ ἴσου Διὶ Πραξιτέλης καὶ πᾶν ὅ τι κειμήλιον εὐπρεπὲς οἴκοι φυλάττοιτο, τοῦτ᾿ ἦν ἀνάθημα τῆς θεοῦ. πέρας αἱ σφοδραὶ τῶν ἐν αὐτῷ πόθων ἐπιτάσεις ἀπενοήθησαν, εὑρέθη δὲ τόλμα τῆς ἐπιθυμίας μαστροπός· ἤδη γὰρ ἐπὶ δύσιν ἡλίου κλίνοντος ἠρέμα λαθὼν τοὺς παρόντας ὄπισθε τῆς θύρας παρεισερρύη καὶ στὰς ἀφανὴς ἐνδοτάτω σχεδὸν οὐδ᾿ ἀναπνέων ἠτρέμει, συνήθως δὲ τῶν ζακόρων ἔξωθεν τὴν θύραν ἐφελκυσαμένων ἔνδον ὁ καινὸς Ἀγχίσης καθεῖρκτο. καὶ τί γὰρ ἀρρήτου νυκτὸς ἐγὼ τόλμαν ἡ λάλος ἐπ᾿ ἀκριβὲς ὑμῖν διηγοῦμαι; τῶν ἐρωτικῶν περιπλοκῶν ἴχνη ταῦτα μεθ᾿ ἡμέραν ὤφθη καὶ τὸν σπίλον εἶχεν ἡ θεὸς ὧν ἔπαθεν ἔλεγχον. αὐτόν γε μὴν τὸν νεανίαν, ὡς ὁ δημώδης ἱστορεῖ λόγος, ἢ κατὰ πετρῶν φασιν ἢ κατὰ πελαγίου κύματος ἐνεχθέντα παντελῶς ἀφανῆ γενέσθαι. |

|

[17] While the temple-woman was recounting this, Charikles interrupted her account with a shout and said, “Women therefore inspire love even when made of stone. But what would have happened if we had seen such beauty alive and breathing? Would not that single night have been valued as highly as the sceptre of Zeus?” But Kallikratidas smiled and said, “We don’t know as yet, Charikles, whether we won’t hear many stories of this sort when we come to Thespiai.[22] Even now in this we have a clear proof of the truth about the Aphrodite whom you hold in such esteem.” When Charikles asked how this was, I thought Kallikratidas made a very convincing reply. For he said that, although the love-struck youth had seized the chance to enjoy a whole uninterrupted night and had complete liberty to glut his passion, he nevertheless made love to the marble as though to a boy, because, I’m sure, he didn’t want to be confronted by the female parts. This occasioned much snarling argument, till I put an end to the confusion and uproar by saying, “Friends, you must keep to orderly enquiry, as is the proper habit of educated people. You must therefore make an end of this disorderly, inconclusive contentiousness and each in turn exert yourself to defend your own opinion; for it’s not yet the time to leave for the ship, and we must employ that free time for enjoyment and also for such serious matters as can combine pleasure and profit. Therefore let us leave the temple, since great numbers of the pious are coming in, and let us turn aside into one of the feasting-places, so that we can have peace and quiet to hear and to say whatever we wish. But remember that he who is vanquished will never again vex our ears on similar topics.” [18] This suggestion of mine pleased them and after they had agreed to it we left the temple. I was enjoying myself as I was weighed down by no cares, but they were rolling mighty cogitations up and down in their thoughts, as though they were about to compete for the leading place in the processions at Plataia.[23] When we had come to a thickly shaded spot that afforded relief for the summer heat, I said, “This is a pleasant place, for the cicadas chirp melodiously overhead.” Then I sat down between them in right judicial manner, bearing on my brows all the gravity of the Heliaia[24] itself. When I had suggested to them that I should draw lots to decide who should speak first, and Charikles had drawn this privilege, I bade him begin the debate at once. |

[17] ταῦτα τῆς ζακόρου διηγουμένης μεταξὺ τοῦ λόγου διαβοήσας εἶπεν ὁ Χαρικλῆς, Οὐκοῦν τὸ θῆλυ, κἂν λίθινον ᾖ, φιλεῖται. τί δ᾿, εἴ τις ἔμψυχον εἶδε τοιοῦτο κάλλος; ἆρ᾿ οὐκ ἂν ἡ μία νὺξ τῶν τοῦ Διὸς σκήπτρων ἐτιμᾶτο; μειδιάσας δὲ ὁ Καλλικρατίδας, Οὐδέπω, φησίν, ἴσμεν, ὦ Χαρίκλεις, εἰ πολλῶν ἀκουσόμεθα τοιούτων διηγημάτων, ὅταν ἐν Θεσπιαῖς γενώμεθα. καὶ νῦν δὲ τῆς ἀπὸ σοῦ ζηλουμένης Ἀφροδίτης ἐναργές ἐστι τοῦτο δεῖγμα. Πῶς; ἐρομένου τοῦ Χαρικλέους, ἄγαν πιθανῶς ἔδοξέ μοι λέγειν ὁ Καλλικρατίδας· ἔφη γὰρ ὡς ὁ ἐρασθεὶς νεανίας παννύχου σχολῆς λαβόμενος, ὥσθ᾿ ὅλην τοῦ πάθους ἔχειν ἐξουσίαν κορεσθῆναι, παιδικῶς τῷ λίθῳ προσωμίλησεν βουληθεὶς οἶδ᾿ ὅτι μηδὲν πρόσθεν1 εἶναι τὸ θῆλυ. πολλῶν οὖν ἀκρίτων ἀφυλακτουμένων λόγων τὸν συμμιγῆ καταπαύσας ἐγὼ θόρυβον, Ἄνδρες, εἶπον, ἑταῖροι, τῆς κατὰ κόσμον ἔχεσθε ζητήσεως, ὡς εὐπρεπὴς νόμος ἐστὶν παιδείας. ἀπαλλαγέντες οὖν τῆς ἀτάκτου καὶ πέρας οὐδὲν ἐχούσης φιλονεικίας ἐν μέρει ὑπὲρ τῆς αὐτὸς ἑαυτοῦ δόξης ἑκάτερος ἀποτείνασθε· καὶ γὰρ οὐδέπω καιρὸς ἐπὶ ναῦν ἀπιέναι· τῇ δὲ σχολῇ καταχρηστέον εἰς ἱλαρίαν καὶ μετὰ τέρψεως ὠφελῆσαι δυναμένην σπουδήν. ὑπεκστάντες οὖν τοῦ νεὼ—πολὺς γὰρ ὁ κατ᾿ εὐσέβειαν ἐπιφοιτῶν—εἰς ἕν τι τῶν συμποσίων ἀποκλίνωμεν, ὅπως δι᾿ ἠρεμίας ἀκούειν τε καὶ λέγειν ἅττ᾿ ἂν ᾖ βουλομένοις ἐξῇ. μέμνησθε δὲ ὡς ὁ τήμερον ἡττηθεὶς οὐκέτ᾿ αὖθις ἡμῖν περὶ τῶν ἴσων διοχλήσει. [18] καλῶς δ᾿ ἔδοξα ταῦτα λέγειν καὶ συγκαταινεσάντων ἐξῄειμεν, ἐγὼ μὲν ἡδόμενος οὐδεμιᾶς με πιεζούσης φροντίδος, οἱδ᾿ ἐπὶ συννοίας μεγάλην ἐν ἑαυτοῖς σκέψιν ἄνω καὶ κάτω κυκλοῦντες ὡς περὶ τῆς προπομπίας ἀγωνιούμενοι Πλαταιᾶσιν. ἐπεὶ δ᾿ ἥκομεν εἴς τι συνηρεφὲς καὶ παλίνσκιον ὥρᾳ θέρους ἀναπαυστήριον, Ἡδύς, εἰπών, ὁ τόπος, ἐγώ, καὶ γὰρ οἱ κατὰ κορυφὴν λιγυρὸν ὑπηχοῦσι τέττιγες, ἐν μέσῳ πάνυ δικαστικῶς καθεζόμην αὐτὴν ἐπὶ ταῖς ὀφρύσιν τὴν Ἡλιαίαν ἔχων. προθεὶς3 δ᾿ ἀμφοτέροις κλῆρον ὑπὲρ τοῦ τίνα χρὴ πρῶτον εἰπεῖν, ἐπειδὴ Χαρικλῆς ἐλελόγχει πρότερον, εὐθὺς ἐνάρχεσθαι τοῦ λόγου διεκελευσάμην. |

|

[19] He rubbed his brow lightly with his hand and after a short pause began as follows: “To you, Aphrodite, my queen, do my prayers appeal to give help in my advocacy of your cause. For every enterprise attains complete perfection if you shed on it but the faintest degree of the arts of persuasion that are your very own; but discourses on love have particular need of you. For you are their only true mother. Come, you who are the most feminine of all, plead the cause of womankind, and of your grace allow men to remain male, as they were born to be. Therefore do I at the very outset of my discourse call as witness to back my plea the first mother and earliest root of every creature, that sacred origin of all things, I mean, who in the beginning established earth, air, fire and water, the elements of the universe, and, by blending these with each other, brought to life everything that has breath. Knowing that we are something created from perishable matter and that the life-time assigned each of us by fate is but short, she contrived that the death of one thing should be the birth of another and meted out fresh births to compensate for what dies, so that by replacing one another we live for ever. But, since it was impossible for anything to be born from but a single source, she devised in each species two types. For she allowed males as their peculiar privilege to ejaculate semen, and made females to be a vessel as it were for the reception of seed, and, imbuing both sexes with a common desire, she linked them to each other, ordaining as a sacred law of necessity that each should retain its own nature and that neither should the female grow unnaturally masculine nor the male be unbecomingly soft. For this reason the intercourse of men with women has till this day preserved the life of men by an undying succession, and no man can boast he is the son only of a man; no, people pay equal homage to their mother and to their father, and all honours are still retained equally by these two revered names. [20] In the beginning therefore, since human life was still full of heroic thought and honoured the virtues that kept men close to gods, it obeyed the laws made by nature, and men, linking themselves to women according to the proper limits imposed by age, became fathers of sterling children. But gradually the passing years degenerated from such nobility to the lowest depths of hedonism and cut out strange and extraordinary paths to enjoyment. Then luxury, daring all, transgressed the laws of nature herself. And who ever was the first to look at the male as though at a female after using violence like a tyrant or else shameless persuasion? The same sex entered the same bed. Though they saw themselves embracing each other, they were ashamed neither at what they did nor at what they had done to them, and, sowing their seed, to quote the proverb, on barren rocks they bought a little pleasure at the cost of great disgrace. [21] The daring of some men has advanced so far in tyrannical violence as even to wreak sacrilege upon nature with the knife. By depriving males of their masculinity they have found wider ranges of pleasure. But those who become wretched and luckless in order to be boys for longer remain male no longer, being a perplexing riddle of dual gender, neither being kept for the functions to which they have been born nor yet having the thing into which they have been changed. The bloom that has lingered with them in their youth makes them fade prematurely into old age. For at the same moment they are counted as boys and have become old without any interval of manhood. Thus foul self-indulgence, teacher of every wickedness, devising one shameless pleasure after another, has plunged all the way down to that infection which cannot even be mentioned with decency, in order to leave no area of lust unexplored. |

[19] ὁ δὲ τῇ δεξιᾷ τὸ πρόσωπον ἀνατρίψας ἡσυχῇ καὶ μικρὸν ἐπισχὼν ἄρχεται τῇδέ πῃ, Σέ, δέσποινα, τῶν ὑπὲρ σοῦ λόγων, Ἀφροδίτη, σὲ βοηθὸν αἱ ἐμαὶ δεήσεις καλοῦσιν· ἅπαντι μὲν γὰρ ἔργῳ κἂν βραχὺ τῆς ἰδίας πειθοῦς ἐπιστάξῃς, τελειότατόν ἐστιν, οἱ δ᾿ ἐρωτικοὶ λόγοι περιττῶς σοῦ δέονται· σὺ γὰρ αὐτῶν γνησιωτάτη μήτηρ. ἴθι δὴ γυναιξὶν συνήγορος ἡ θήλεια, χάρισαι δὲ καὶ τοῖς ἀνδράσι μένειν ἄρρεσιν, ὡς ἐγεννήθησαν. ἔγωγ᾿ οὖν εὐθὺς ἐν ἀρχῇ τοῦ λόγου τὴν προμήτορα καὶ πάσης γενέσεως πρωτόρριζον ὧν ἀξιῶ μάρτυρα ἐπικαλοῦμαι, λέγω δὲ τὴν ἱερὰν τῶν ὅλων φύσιν, ἣ τὰ πρῶτα πηξαμένη στοιχεῖα τοῦ κόσμου γῆν ἀέρα πῦρ ὕδωρ τῇ πρὸς ἄλληλα τούτων ἐπικράσει πᾶν ἐζῳογόνησεν ἔμψυχον. ἐπισταμένη δ᾿ ὅτι θνητῆς ἐσμὲν ὕλης δημιούργημα καὶ βραχὺς χρόνος ὁ τοῦ ζῆν ἑκάστῳ καθείμαρται, τὴν ἑτέρου φθορὰν ἄλλου γένεσιν ἐμηχανήσατο καὶ τῷ θνῄσκοντι τὸ τικτόμενον ἀντεμέτρησεν, ἵνα ταῖς παρ᾿ ἀλλήλων διαδοχαῖς εἰς τὸν ἀεὶ χρόνον ζῶμεν. ἐπεὶ δ᾿ ἦν ἄπορον ἐξ ἑνός τι γεννᾶσθαι, διπλῆν ἐν ἑκάστῳ φύσιν ἐμηχανήσατο· τοῖς μὲν γὰρ ἄρρεσιν ἰδίας καταβολὰς σπερμάτων χαρισαμένη, τὸ θῆλυ δ᾿ ὥσπερ γονῆς τι δοχεῖον [ἀγγεῖον] ἀποφήνασα, κοινὸν οὖν ἀμφοτέρῳ γένει πόθον ἐγκερασαμένη συνέζευξεν ἀλλήλοις, θεσμὸν ἀνάγκης ὅσιον καταγράψασα μένειν ἐπὶ τῆς ἰδίας φύσεως ἑκάτερον, καὶ μήτε τὸ θῆλυ παρὰ φύσιν ἀρρενοῦσθαι μήτε τἄρρεν ἀπρεπῶς μαλακίζεσθαι. διὰ τοῦθ᾿ αἱ σὺν γυναιξὶν ἀνδρῶν ὁμιλίαι μέχρι δεῦρο τὸν ἀνθρώπινον βίον ἀθανάτοις διαδοχαῖς φυλάττουσιν· οὐδεὶς δ᾿ ἀνὴρ ἀπ᾿ ἀνδρὸς αὐχεῖ γενέσθαι. δυοῖν δ᾿ ὀνομάτοιν σεβασμίοιν πᾶσαι τιμαὶ μένουσιν ἐξ ἴσου πατρὶ μητέρα προσκυνούντων. [20] κατ᾿ ἀρχὰς μὲν οὖν ἔθ᾿ ἡρωϊκὰ φρονῶν ὁ βίος καὶ τὴν γείτονα θεῶν σέβων ἀρετὴν οἷς ἐνομοθέτησεν ἡ φύσις ἐπειθάρχει, καὶ καθ᾿ ἡλικίας μέτρα γυναιξὶ ζευγνύμενοι γενναίων πατέρες ἐγίνοντο τέκνων· κατὰ μικρὸν δ᾿ ὁ χρόνος ἀπ᾿ ἐκείνου τοῦ μεγέθους ἐς τὰ τῆς ἡδονῆς καταβαίνων βάραθρα ξένας ὁδοὺς καὶ παρηλλαγμένας ἀπολαύσεων ἔτεμνεν. εἶθ᾿ ἡ πάντα τολμῶσα τρυφὴ τὴν φύσιν αὐτὴν παρενόμησεν· καὶ τίς ἄρα πρῶτος ὀφθαλμοῖς τὸ ἄρρεν εἶδεν ὡς θῆλυ, δυοῖν θάτερον ἢ τυραννικῶς βιασάμενος ἢ πείσας πανούργως; συνῆλθεν δ᾿ εἰς μίαν κοίτην μία φύσις· αὑτοὺς δ᾿ ἐν ἀλλήλοις ὁρῶντες οὔθ᾿ ἃ δρῶσιν οὔθ᾿ ἃ πάσχουσιν ᾐδοῦντο, κατὰ πετρῶν δέ, φασίν, ἀγόνων σπείροντες ὀλίγης ἡδονῆς ἀντικατηλλάξαντο μεγάλην ἀδοξίαν. [21] ἐνίοις γε μὴν εἰς τοσοῦτον τυραννικῆς βίας ἡ τόλμα προέκοψεν, ὡς μέχρι σιδήρῳ τὴν φύσιν ἱεροσυλῆσαι· τῶν δ᾿ ἀρρένων τὸ ἄρρεν ἐκκενώσαντες εὗρον ἡδονῆς παρέλκοντα μέτρα. οἱ δ᾿ ἄθλιοι καὶ δυστυχεῖς ἵν᾿ ἐπὶ πλέον ὦσι παῖδες, οὐδὲ ἔτι μένουσιν ἄνδρες, ἀμφίβολον αἴνιγμα διπλῆς φύσεως, οὔτ᾿ εἰς ὃ γεγέννηνται φυλαχθέντες οὔτ᾿ ἔχοντες ἐφ᾿ ὃ μετέβησαν· τὸ δ᾿ ἐν νεότητι παραμεῖναν ἄνθος εἰς γῆρας αὐτοὺς μαραίνειν πρόωρον. ἅμα γὰρ ἐν παισὶν ἀριθμοῦνται, καὶ γεγηράκασιν οὐδὲν ἀνδρῶν μεταίχμιον ἔχοντες. οὕτως ἡ μιαρὰ καὶ παντὸς κακοῦ διδάσκαλος τρυφὴ ἄλλην ἀπ᾿ ἄλλης ἡδονὰς ἀναισχύντους ἐπινοοῦσα μέχρι τῆς οὐδὲ ῥηθῆναι δυναμένης εὐπρεπῶς νόσου κατώλισθεν, ἵνα μηδὲν ἀγνοῇ μέρος ἀσελγείας. |

|

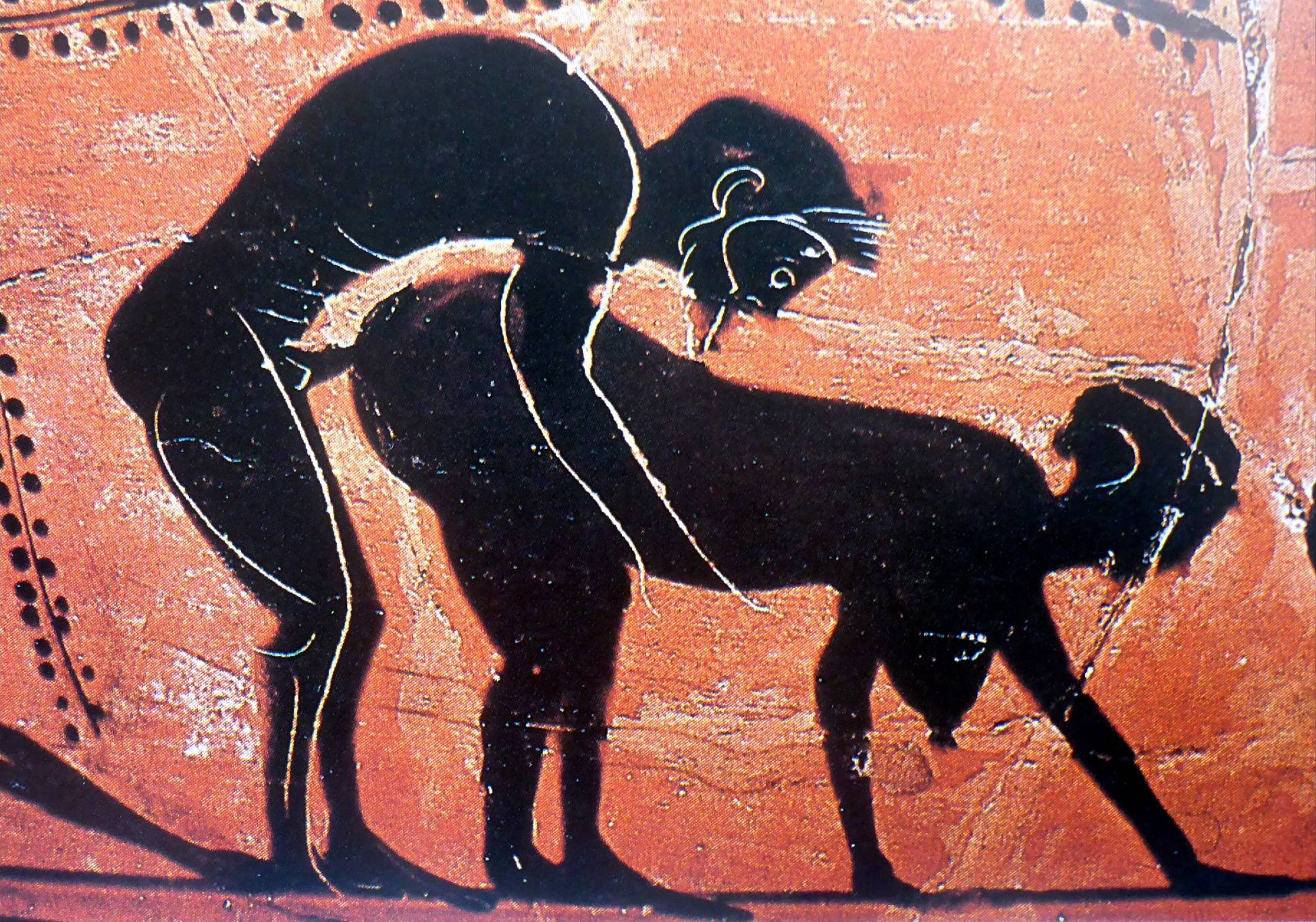

[22] If each man abided by the ordinances prescribed for us by Providence, we should be satisfied with intercourse with women and life would be uncorrupted by anything shameful. Certainly, among animals incapable of debasing anything through depravity of disposition the laws of nature are preserved undefiled. Lions have no passion for lions but love in due season evokes in them desire for the females of their kind. The bull, monarch of the herd, mounts cows, and the ram fills the whole flock with seed from the male. Furthermore do not boars seek to lie with sows? Do not wolves mate. with she-wolves? And, to speak in general terms, neither the birds whose wings whir on high, nor the creatures whose lot is a wet one beneath the water nor yet any creatures upon land strive for intercourse with fellow males, but the decisions of Providence remain unchanged. But you who are wrongly praised for wisdom, you beasts truly contemptible, you humans, by what strange infection have you been brought to lawlessness and incited to outrage each other? With what blind insensibility have you engulfed your souls that you have missed the mark in both directions, avoiding what you ought to pursue, and pursuing what you ought to avoid? If each and every man should choose to emulate such conduct, the human race will come to a complete end. [23] But at this point disciples of Sokrates can resurrect that wonderful argument by which boys’ ears as yet incapable of perfect logic are deceived, though those whose minds have already reached their full powers would not be led astray by them. For they affect a love for the soul and, being ashamed to pay court to bodily beauty, call themselves lovers of virtue. This often tempts me to cackle with laughter. For what is wrong with you, grave philosophers, that you dismiss with scorn what has now long given proof of its quality, and has witnesses to its virtue in its becoming grey hairs and its old age, whereas all your wise love is captivated by the young though their reasonings cannot yet decide to what course they will turn? Or is there a law that all ugliness should be thought guilty of viciousness but that the handsome should automatically be praised as good? But indeed, to quote Homer, the great prophet of truth, Although one man is worse in looks, And again the poet has spoken with these words: ‘You did not then have wits to add to looks. Indeed wise Odysseus is praised more than handsome Nireus. [24] How is it then that through you courses no love for wisdom or for justice and the other virtues which have in their allotted station the company of full-grown men, while beauty in boys excites the most ardent fires of passion in you? No doubt, Plato, one ought to have loved Phaidros for the sake of Lysias whom he betrayed! Or would it have been right to love the virtue of Alkibiades[25] because he would mutilate statues of the gods and his drunken cries parodied the initiation rites of Eleusis? Who admits to having been in love with the betrayal of Athens, the fortification of Dekeleia against her, and a life that set its sights on tyranny? But, as godlike Plato says,[26] as long as his beard was not yet fully grown, he was beloved by all. But, after he had passed from boyhood to manhood, during the years when his hitherto immature intellect now had its full powers of reason, he was hated by all. What follows? That it is lovers of youth rather than of wisdom who give honourable names to dishonourable passions and call physical beauty virtue of the soul. But lest I be thought to mention famous men only to vent my hatred, let me say no more on this topic. |

[22] εἰ δὲ ἐφ᾿ ὧν ἡ πρόνοια θεσμῶν ἔταξεν ἡμᾶς, ἕκαστος ἵδρυτο, ταῖς μετὰ γυναικῶν ὁμιλίαις ἂν ἠρκούμεθα καὶ παντὸς ὀνείδους ὁ βίος ἐκαθάρευεν. ἀμέλει παρὰ τοῖς οὐδὲν ἐκ πονηρᾶς διαθέσεως παραχαράξαι δυναμένοις ζῴοις ἄχραντος ἡ τῆς φύσεως νομοθεσία φυλάττεται· λέοντες οὐκ ἐπιμαίνονται λέουσιν, ἀλλ᾿ ἡ κατὰ καιρὸν Ἀφροδίτη πρὸς τὸ θῆλυ τὴν ὄρεξιν αὐτῶν ἐκκαλεῖται· ταῦρος ἀγελάρχης βουσὶν ἐπιθόρνυται, καὶ κριὸς ὅλην τὴν ποίμνην ἄρρενος πληροῖ σπέρματος. τί δέ; οὐ συῶν μὲν εὐνὰς μεταδιώκουσιν κάπροι; λυκαίναις δ᾿ ἐπιμίγνυνται λύκοι; καθόλου δ᾿ εἰπεῖν, οὔθ᾿ οἱ ἀέρια ῥοιζοῦντες ὄρνεις οὔθ᾿ ὅσα τὴν ὑγρὰν καθ᾿ ὕδατος εἴληχεν λῆξιν, ἀλλ᾿ οὐδ᾿ ἐπὶ γῆς τι ζῷον ἄρρενος ὁμιλίας ἐπωρέχθη, μένει δὲ ἀκίνητα τῆς προνοίας τὰ δόγματα. ὑμεῖς δ᾿, ὦ μάτην ἐπὶ τῷ φρονεῖν εὐλογούμενοι, θηρίον ὡς ἀληθῶς φαῦλον, ἄνθρωποι, τίνι καινῇ νόσῷ παρανομήσαντες ἐπὶ τὴν κατ᾿ ἀλλήλων ὕβριν ἠρέθισθε; τίνα τῆς ψυχῆς τυφλὴν ἀναισθησίαν καταχέαντες ἀμφοῖν ἠστοχήκατε φεύγοντες ἃ διώκειν ἔδει καὶ διώκοντες ἀφ᾿ ὧν ἔδει φεύγειν; καὶ καθ᾿ ἕνα τοιαῦτα ζηλοῦν πάντων ἑλομένων οὐδὲ εἷς ἔσται. [23] ἀλλὰ γὰρ ἐνταῦθα τοῖς Σωκρατικοῖς ὁ θαυμαστὸς ἀναφύεται λόγος, ὑφ᾿ οὗ παιδικαὶ μὲν ἀκοαὶ τελείων ἐνδεεῖς λογισμῶν φενακίζονται· τὸ δ᾿ ἤδη κατὰ φρόνησιν ἐς ἄκρον ἔχον οὐκ ἂν ὑπαχθῆναι δύναιτο· ψυχῆς γὰρ ἔρωτα πλάττονται καὶ τὸ τοῦ σώματος εὔμορφον αἰδούμενοι φιλεῖν ἀρετῆς καλοῦσιν αὑτοὺς ἐραστάς. ἐφ᾿ οἷς μοι πολλάκις καγχάζειν ἐπέρχεται. τί γὰρ παθόντες, ὦ σεμνοὶ φιλόσοφοι, τὸ μὲν ἤδη μακρῷ χρόνῳ δεδωκὸς ἑαυτοῦ πεῖραν ὁποῖόν ἐστιν, ᾧ πολιὰ προσήκουσα καὶ γῆρας ἀρετὴν μαρτυρεῖ, δι᾿ ὀλιγωρίας παραπέμπετε, πᾶς δὲ ὁ σοφὸς ἔρως ἐπὶ τὸ1 νέον ἐπτόηται, μηδέπω τῶν λογισμῶν ἐν αὐτῷ πρὸς ἃ τραπήσονται κρίσιν ἐχόντων; ἢ νόμος ἐστίν, πᾶσαν μὲν ἀμορφίαν πονηρίας εἶναι κατάκριτον, εὐθὺ δ᾿ ὡς ἀγαθὸν ἐπαινεῖσθαι τὸν καλόν; ἀλλά τοι κατὰ τὸν μέγαν ἀληθείας προφήτην Ὅμηρον εἶδός τις ἀκιδνότερος πέλει ἀνήρ, καὶ πάλιν εἶπέ που λέγων· οὐκ ἄρα σοί γ᾿ ἐπὶ εἴδεϊ καὶ φρένες ἀμέλει τοῦ καλοῦ Νιρέως ὁ σοφὸς Ὀδυσσεὺς πλέον ἐπαινεῖται. [24] πῶς οὖν φρονήσεως μὲν ἢ δικαιοσύνης τῶν τε λοιπῶν ἀρετῶν, αἳ τελείοις ἀνδράσιν σύγκληρον εἰλήχασιν τάξιν, οὐδεὶς ἔρως ἐντρέχει, τὸ δ᾿ ἐν παισὶ κάλλος ὀξυτάτας παθῶν ὁρμὰς ἐγείρει; πάνυ γοῦν ἐρᾶν ἔδει Φαίδρου διὰ Λυσίαν, ὦ Πλάτων, ὃν προὔδωκεν. ἢ τὴν ἀρετὴν εἰκὸς ἦν Ἀλικιβάδου φιλεῖν, διότι ἠκρωτηριάζετο τὰ θεῶν ἀγάλματα καὶ τὴν ἐν Ἐλευσῖνι τελετὴν αἱ παρὰ πότον ἐξωρχοῦντο φωναί; τίς ἐραστὴς ὁμολογεῖ γενέσθαι προδιδομένων Ἀθηνῶν καὶ Δεκελείας ἐπιτειχιζομένης καὶ βίου τυραννίδα βλέποντος; ἀλλ᾿ ἄχρι μὲν οὐδέπω κατὰ τὸν ἱερὸν Πλάτωνα πώγωνος ἐπίμπλατο, πᾶσιν ἐπέραστος ἦν· μεταβὰς δ᾿ ἀπὸ τοῦ παιδὸς εἰς τὸν ἄνδρα, καθ᾿ ἣν ἡλικίαν ἡ τέως ἀτελὴς φρόνησις ὁλόκληρον εἶχε τὸν λογισμόν, ὑπὸ πάντων ἐμισεῖτο. τί δή; πάθεσιν αἰσχροῖς ὀνομάτων ἐπιγράφοντες αἰδῶ ψυχῆς ἀρετὴν λέγουσι τὴν σώματος εὐπρέπειαν οἱ φιλόνεοι μᾶλλον ἢ φιλόσοφοι. καὶ ταῦτα μὲν ἡμῖν ὑπὲρ τοῦ μὴ δοκεῖν ἐπισήμων ἀνδρῶν φιλαπεχθημόνως μνημονεύειν ἐπὶ τοσοῦτον εἰρήσθω. |

|

[25] To quit this highly serious plane and descend somewhat to your level of pleasure, Kallikratidas, I shall show that the services rendered by a woman are far superior to those of a boy. In the first place I consider that all kinds of enjoyment give greater delight if of longer duration. For swift pleasure flits by and is gone before we can recognise it, but delights are enhanced by being prolonged. How I wish that stingy fate had allotted us long terms of life and it consisted entirely of unbroken good health with no grief preying on our minds. For then we should spend all our days in feasting and holiday. But, since envious Fortune has grudged us these greater benefits, amongst those that we have the sweetest are those that last. Thus from maidenhood to middle age, before the time when the last wrinkles of old age finally spread over her face, a woman is a pleasant armful for a man to embrace, and, even if the beauty of her prime is past, yet “With wiser tongue [26] But the very man who should make attempts on a boy of twenty seems to me to be unnaturally lustful and pursuing an equivocal love. For then the limbs, being large and manly, are hard, the chins that once were soft are rough and covered with bristles, and the well-developed thighs are as it were sullied with hairs. And as for the parts less visible than these, I leave knowledge of them to you who have tried them! But ever does her attractive skin give radiance to every part of a woman and her luxuriant ringlets of hair, hanging down from her head, bloom with a dusky beauty that rivals the hyacinths, some of them streaming over her back to grace her shoulders, and others over her ears and temples curlier by far than the celery in the meadow. But the rest of her person has not a hair growing on it and shines more pellucidly than amber, to quote the proverb, or Sidonian crystal. [27] But why do we not pursue those pleasures that are mutual and bring equal delight to the passive and to the active partners? For, generally speaking, unlike irrational animals we do not find solitary existences acceptable, but we are linked by a sociable fellowship and consider blessings sweeter and hardships lighter when shared. Hence was instituted the table that is shared, and, setting before us the board that is the mediator of friendship, we mete out to our bellies the enjoyment due to them, not drinking Thasian wine, for example, by ourselves, or stuffing ourselves with expensive dishes on our own, but each man thinks pleasant what he enjoys along with another, and in sharing our pleasures we find greater enjoyment. Now men’s intercourse with women involves giving like enjoyment in return. For the two sexes part with pleasure only if they have had an equal effect on each other -- unless we ought rather to heed the verdict of Tiresias that the woman’s enjoyment is twice as great as the man’s.[28] And I think it honourable for men not to wish for a selfish pleasure or to seek to gain some private benefit by receiving from anyone the sum total of enjoyment, but to share what they obtain and to requite like with like. But no one could be so mad as to say this in the case of boys. No, the active lover, according to his view of the matter, departs after having obtained an exquisite pleasure, but the one outraged suffers pain and tears at first, though the pain relents somewhat with time and you will, men say, cause him no further discomfort, but of pleasure he has none at all. And, if I may make a rather far-fetched point, but one I should make as we are in the precinct of Aphrodite, a woman, Kallikratidas, may be used like a boy, so that one can have enjoyment by opening up two paths to pleasure, but a male has no way of bestowing the pleasure a woman gives. |

[25] Μικρὰ δ᾿ ἀπὸ τῆς ἄγαν σπουδῆς, ὠ Καλλικρατίδα, ἐπὶ τὴν ὑμετέραν καταβὰς ἡδονὴν ἐπιδείξω παιδικῆς χρήσεως πολὺ τὴν γυναικείαν ἀμείνω. καὶ τό γε πρῶτον ἐγὼ πᾶσαν ἀπόλαυσιν ἡγοῦμαι τερπνοτέραν εἶναι τὴν χρονιωτέραν· ὀξεῖα γὰρ ἡδονὴ παραπτᾶσα φθάνει πρὶν ἢ γνωσθῆναι πεπαυμένη, τὸ δ᾿ εὐφραῖνον ἐν τῷ παρέλκοντι κρεῖττον. ὡς εἴθε καὶ βίου μακρὰς προθεσμίας ἡ μικρολόγος ἡμῖν ἐπέκλωσεν Μοῖρα καὶ τὸ πᾶν ἦν διηνεκὴς ὑγίεια μηδεμιᾶς λύπης τὴν διάνοιαν ἐκνεμομένης· ἑορτὴν γὰρ ἂν καὶ πανήγυριν τὸν ὅλον χρόνον ἤγομεν. ἀλλ᾿ ἐπεὶ τῶν μειζόνων ἀγαθῶν ὁ βάσκανος δαίμων ἐνεμέσησεν, ἔν γε τοῖς παροῦσιν ἥδιστα τὰ παρέλκοντα. γυνὴ μὲν οὖν ἀπὸ παρθένου μέχρι μέσης ἡλικίας, πρὶν ἢ τελέως τὴν ἐσχάτην ῥυτίδα τοῦ γήρως ἐπιδραμεῖν, εὐάγκαλον ἀνδράσιν ὁμίλημα, κἂν παρέλθῃ τὰ τῆς ὥρας, ὅμως ἡμπειρία [26] εἰ δ᾿ εἴκοσιν ἐτῶν ἀποπειρῴη παῖδά τις, αὐτὸς ἔμοιγε δοκεῖ πασχητιᾶν ἀμφίβολον Ἀφροδίτην μεταδιώκων· σκληροὶ γὰρ οἱ τῶν μελῶν ἀπανδρωθέντες ὄγκοι καὶ τραχὺ μὲν ἀντὶ τοῦ πάλαι μαλακοῦ πυκασθὲν ἰούλοις τὸ γένειον, οἱ δ᾿ εὐφυεῖς μηροὶ θριξὶν ὡσπερεὶ ῥυπῶντες· ἃ δ᾿ ἐστὶ τούτων ἀφανέστερα, τοῖς πεπειρακόσιν ὑμῖν εἰδέναι παρίημι. γυναικὶ δὲ ἀεὶ πάσῃ ἡ τοῦ χρώματος ἐπιστίλβει χάρις, καὶ δαψιλεῖς μὲν ἀπὸ τῆς κεφαλῆς βοστρύχων ἕλικες ὑακίνθοις τὸ καλὸν ἀνθοῦσιν ὅμοια πορφύροντες οἱ μὲν ἐπινώτιοι κέχυνται μεταφρένων κόσμος, οἱ δὲ παρ᾿ ὦτα καὶ κροτάφους πολὺ τῶν ἐν λειμῶνι οὐλότεροι σελίνων. τὸ δ᾿ ἄλλο σῶμα μηδ᾿ ἀκαρῆ τριχὸς αὐταῖς ὑποφυομένης ἠλέκτρου, φασίν, ἢ Σιδωνίας ὑέλου διαφεγγέστερον ἀπαστράπτει. [27] τί δ᾿ οὐχὶ τῶν ἡδονῶν καὶ τὰς ἀντιπαθεῖς μεταδιωκτέον, ἐπειδὰν ἐξ ἴσου τοῖς διατιθεῖσιν2 οἱ πάσχοντες εὐφραίνωνται; σχεδὸν γὰρ οὐ κατὰ ταὐτὰ τοῖς ἀλόγοις ζῴοις τὰς μονήρεις διατριβὰς ἀσμενίζομεν, ἀλλά πως φιλεταίρῳ κοινωνίᾳ συζυγέντες ἡδίω τά τε ἀγαθὰ σὺν ἀλλήλοις ἡγούμεθα καὶ τὰ δυσχερῆ κουφότερα μετ᾿ ἀλλήλων. ὅθεν εὑρέθη τράπεζα κοινή· καὶ φιλίας μεσῖτιν ἑστίαν παραθέμενοι γαστρὶ τὴν ὀφειλομένην ἀπομετροῦμεν ἀπόλαυσιν, οὐ μόνοι τὸν Θάσιον, εἰ τύχοι, πίνοντες οἶνον οὐδὲ καθ᾿ αὑτοὺς τῶν πολυτελῶν πιμπλάμενοι σιτίων, ἀλλὰ δοκεῖ περπνὸν ἑκάστῳ τὸ μετ᾿ ἄλλου, καὶ τὰς ἡδονὰς κοινωσάμενοι μᾶλλον εὐφραινόμεθα. αἱ μὲν γυναικεῖοι σύνοδοι τῆς ἀπολαύσεως ἀντίδοσιν ὁμοίαν ἔχουσιν· ἀλλήλους γὰρ ἐξ ἴσου διαθέντες ἡδέως ἀπηλλάγησαν, εἴ γε μὴ δικαστῇ Τειρεσίᾳ προσεκτέον, ὅτι ἡ θήλεια τέρψις ὅλῃ μοίρᾳ πλεονεκτεῖ τὴν ἄρρενα. καλὸν δ᾿ οἶμαι, μὴ φιλαύτως ἀπολαῦσαι θελήσαντας, ὅπως ἰδίᾳ τι χρηστὸν ἀποίσονται σκοπεῖν ὅλην παρά του λαμβάνοντας ἡδονήν, ἀλλ᾿ ἐκεῖνο μερισαμένους οὗ τυγχάνουσιν ἀντιπαρασχεῖν ὅμοια. τοῦτο δ᾿ οὐκ ἂν ἐπὶ παίδων εἴποι τις, οὐχ οὕτω μέμηνεν, ἀλλ᾿ ὁ μὲν διαθείς, ᾗ νομίζει ποτὲ ταῦτα, τὴν ἡδονὴν ἐξαίρετον λαβὼν ἀπέρχεται, τῷ δὲ ὑβρισμένῳ κατ᾿ ἀρχὰς μὲν ὀδύναι καὶ δάκρυα, μικρὸν δὲ ὑπὸ χρόνου τῆς ἀλγηδόνος χαλασάσης πλέον, ὥς φασιν, οὐδὲν ἂν ὀχλήσειας, ἡδονὴ δ᾿ οὐδ᾿ ἡτισοῦν. εἰ δὲ δεῖ τι καὶ περιεργότερον εἰπεῖν—δεῖ δὲ ἐν Ἀφροδίτης τεμένει—γυναικὶ μέν, ὦ Καλλικρατίδα, καὶ παιδικώτερον χρώμενον ἔξεστιν εὐφρανθῆναι διπλασίας ἀπολαύσεως ὁδοὺς ἀνύσαντα, τὸ δὲ ἄρρεν οὐδενὶ τρόπῳ χαρίζεται θήλειαν ἀπόλαυσιν. |

| [28] Therefore, if even men like you, Kallikratidas, can find satisfaction in women, let us males fence ourselves off from each other; but, if males find intercourse with males acceptable, henceforth let women too love each other. Come now, epoch of the future, legislator of strange pleasures, devise fresh paths for male lusts, but bestow the same privilege upon women, and let them have intercourse with each other just as men do. Let them strap to themselves cunningly contrived instruments of lechery, those mysterious monstrosities devoid of seed, and let woman lie with woman as does a man. Let wanton tribadism -- that word seldom heard, which I feel ashamed even to utter -- freely parade itself, and let our women’s chambers emulate Philainis[29], disgracing themselves with Sapphic amours. And how much better that a woman should invade the provinces of male wantonness than that the nobility of the male sex should become effeminate and play the part of a woman! | [28] ὥστ᾿ εἰ ἡ μὲν καὶ ὑμῖν ἀρέσκειν δύναται, πρὸς ἀλλήλους δὴ ἡμεῖς ἀποτειχισώμεθα, εἰ δὲ τοῖς ἄρρεσιν εὐπρεπεῖς αἱ μετὰ ἀρρένων ὁμιλίαι, πρὸς τὸ λοιπὸν ἐράτωσαν ἀλλήλων καὶ γυναῖκες. ἄγε νῦν, ὦ νεώτερε χρόνε καὶ τῶν ξένων ἡδονῶν νομοθέτα, καινὰς ὁδοὺς ἄρρενος τρυφῆς ἐπινοήσας χάρισαι τὴν ἴσην ἐξουσίαν καὶ γυναιξίν, καὶ ἀλλήλαις ὁμιλησάτωσαν ὡς ἄνδρες· ἀσελγῶν δὲ ὀργάνων ὑποζυγωσάμεναι τέχνασμα, ἀσπόρων6 τεράστιον αἴνιγμα, κοιμάσθωσαν γυνὴ μετὰ γυναικὸς ὡς ἀνήρ· τὸ δὲ εἰς ἀκοὴν σπανίως ἧκον ὄνομα—αἰσχύνομαι καὶ λέγειν—τῆς τριβακῆς ἀσελγείας ἀνέδην πομπευέτω. πᾶσα δ᾿ ἡμῶν ἡ γυναικωνῖτις ἔστω Φιλαινὶς ἀνδρογύνους ἔρωτας ἀσχημονοῦσα. καὶ πόσῳ κρεῖττον εἰς ἄρρενα τρυφὴν βιάζεσθαι γυναῖκα ἢ τὸ γενναῖον ἀνδρῶν εἰς γυναῖκα θηλύνεσθαι; |

|

[29] In the midst of this intense and impassioned speech Charikles stopped with a wild fierce glint in his eyes. It seemed to me that he was also regarding his speech as a ceremony of purification against love of boys. But I, laughing quietly and turning my eyes gently towards the Athenian, said, “It was to decide a sportive piece of fun, Kallikratidas, that I expected to sit as umpire, but somehow or other thanks to Charikles’ vehemence I’ve been brought to face a more serious task. For he has shown an extraordinary degree of passion almost as though he were in the Areopagos[30] contesting a case of murder or arson or indeed poisoning. Therefore the present moment, if any time ever did, demands that you should recall one of the speeches made to the people in the Pnyx and in this one speech of yours should expend all the resources of Athens, of Periklean persuasiveness and of the tongues of the ten orators which were marshalled against the Macedonians.”[31] [30] After waiting for a moment Kallikratidas, who, judging from his expression, appeared to me to be most full of fight, began to discourse in his turn and said: “If the assembly and the law-courts were open to women and they could participate in politics, you would have been elected their general or their champion and they would have honoured you, Charikles, with bronze statues in the market-places. For hardly even those among them thought preeminent for wisdom could, if given full authority to speak, have spoken about themselves with such zeal, no, not even Telesilla[32], who armed herself against the Spartiates, and because of whom Ares is numbered at Argos among the gods of the women, no nor Sappho, the honey-sweet pride of Lesbos or Theano, that daughter of Pythagorean wisdom! Perhaps even Perikles could not have pleaded equally well for Aspasia.[33] But, since it is not improper for men to speak on behalf of women, let us men also speak on behalf of men; and you, Aphrodite, be propitious. For we too honour your son, Eros. |

[29] Τοιαῦτα συντόνως μεταξὺ παθαινόμενος ὁ Χαρικλῆς ἐπαύσατο δεινόν τι καὶ θηριῶδες ἐν τοῖς ὄμμασιν ὑποβλέπων. ἐῴκει δέ μοι καὶ καθαρσίῳ χρῆσθαι πρὸς τοὺς παιδικοὺς ἔρωτας. ἐγὼ δὲ ἡσυχῇ μειδιάσας καὶ πρὸς τὸν Ἀθηναῖον ἠρέμα τὼ ὀφθαλμὼ παραβαλών, Παιδιᾶς, ἔφην, καὶ γέλωτος, ὦ Καλλικρατίδα, δικαστὴς καθεδεῖσθαι προσδοκήσας οὐκ οἶδ᾿ ὅπως ὑπὸ τῆς Χαρικλέους δεινότητος ἐπὶ σπουδαιότερον ἦγμαι· σχεδὸν γὰρ ὡς ἐν Ἀρείῳ πάγῳ περὶ φόνου καὶ πυρκαϊᾶς, ἢ νὴ Δία φαρμάκων ἀγωνιζόμενος ὑπερφυῶς ἐπαθήνατο. καιρὸς οὖν ὁ νῦν, εἴ ποτε καὶ πρότερον, ἀπαιτεῖ σε τὰς Ἀθήνας, Περικλείαν δὲ πειθὼ καὶ τῶν δέκα ῥητόρων τὰς Μακεδόσιν ἀνθωπλισμένας γλώσσας ἐν ἑνὶ τῷ σῷ λόγῳ διατρῖψαι μιᾶς τῶν ἐν Πνυκὶ δημηγοριῶν ἀναμνησθέντι. [30] Μικρὸν οὖν ἐπισχὼν ὁ Καλλικρατίδας—ἐῴκει δὲ ἀπὸ τοῦ προσώπου μοι τεκμαιρομένῳ καὶ λίαν ἀγωνίας μεστὸς εἶναι—λόγων ἀμοιβαίων ἐνάρχεται· Εἰ γυναιξὶν ἐκκλησία καὶ δικαστήρια καὶ πολιτικῶν πραγμάτων ἦν μετουσία, στρατηγὸς ἂν ἢ προστάτης ἐκεχειροτόνησο καί σε χαλκῶν ἀνδριάντων ἐν ταῖς ἀγοραῖς, ὦ Χαρίκλεις, ἐτίμων. σχεδὸν γὰρ οὐδὲ αὐταὶ περὶ αὑτῶν, ὁπόσαι προὔχειν κατὰ σοφίαν ἐδόκουν, εἴ τις αὐταῖς τὴν τοῦ λέγειν ἐξουσίαν ἐφῆκεν, οὕτω μετὰ σπουδῆς ἂν εἶπον, οὐχ ἡ Σπαρτιάταις ἀνθωπλισμένη Τελέσιλλα, δι᾿ ἣν ἐν Ἄργει θεὸς ἀριθμεῖται γυναικῶν Ἄρης· οὐχὶ τὸ μελιχρὸν αὔχημα Λεσβίων Σαπφὼ καὶ ἡ τῆς Πυθαγορείου σοφίας θυγάτηρ Θεανώ· τάχα δ᾿ οὐδὲ Περικλῆς οὕτως ἂν Ἀσπασίᾳ συνηγόρησεν. ἀλλ᾿ ἐπειδήπερ εὐπρεπὲς ἄρρενας ὑπὲρ θηλειῶν λέγειν, εἴπωμεν καὶ ἄνδρες ὑπὲρ ἀνδρῶν. σὺ δὲ ἵλεως, Ἀφροδίτη, γενοῦ· καὶ γὰρ ἡμεῖς τὸν σὸν Ἔρωτα τιμῶμεν. |

|

[31] I thought that our merry contest had gone as far as jest allowed but, since Charikles in his discourse has been minded also to wax philosophical on behalf of women, I have gladly seized my opportunity; for love of males, I say, is the only activity combining both pleasure and virtue. For I would pray that near us, if it were possible, grew that plane-tree which once heard the words of Sokrates, a tree more fortunate than the Academy and the Lyceum, the tree against which Phaidros leaned, as we are told by that holy man endowed with more graces than any other. Perhaps like the oak at Dodona, that sent its sacred voice bursting forth from its branches, that tree itself, still remembering the beauty of Phaidros, would have spoken in praise of love of boys. But that is impossible, “For in between there lies and we are strangers cut off in a foreign land, and Knidos gives Charikles the advantage. Nevertheless we shall not be overcome by fear and betray the truth. [32] Only do you, heavenly spirit, lend me seasonable help, you kindly hierophant of the mysteries of friendship, Eros, who are no mischievous infant as painters light-heartedly portray you, but were already full-grown at your birth, when brought forth by the earliest source of all life. For you gave shape to everything out of dark confused shapelessness. As though you had removed a tomb burying the whole universe alike, you banished that chaos which enveloped it to the recesses of farthest Tartaros, where in truth, “Are gates of iron and thresholds of so that, chained in an impregnable prison, it may be denied any return. Spreading bright light over gloomy night you became the creator of all things both with and without life. But compounding for mortals the special gift of harmony of mind, you united their hearts with the holy sentiment of friendship, so that goodwill might grow in souls still innocent and tender and come to perfect maturity. [33] For marriage is a remedy invented to ensure man’s necessary perpetuity, but only love for males is a noble duty enjoined by a philosophic spirit. Anything cultivated for aesthetic reasons in the midst of abundance is accompanied with greater honour than things which require for their existence immediate need, and beauty is in every way superior to necessity. Thus, as long as human life remained unsophisticated and the daily struggle for existence left it no leisure for improving itself, men were content to limit themselves to bare necessities, and the urgency of their day did not allow them to discover the proper way to live. But, once pressing needs were at an end and the thoughts of each succeeding generation had been released from the shackles of necessity so that they had leisure ever to devise higher things, from that time the arts gradually began to develop. What this process was like we may judge from the more perfected of the crafts. Right from the moment of their birth the earliest men had to search for a remedy against their daily hunger, and, under the duress of immediate need, prevented by their helplessness from choosing what was better, fed on any chance herb, digging up tender roots and eating mostly the fruit of the oak. But after a time this was cast before brute animals, and the careful husbandmen discovered how to sow wheat and barley and saw these renew themselves every year. And not even a madman would maintain that the fruit of the oak is superior to the ear of grain. |

[31] Ἐγὼ μὲν οὖν ἐνόμιζον ἄχρι παιδιᾶς ἱλαρὰν τὴν ἔριν ἡμῶν προκόψαι, ἐπεὶ δὲ οἱ παρὰ τούτου λόγοι καὶ φιλοσοφεῖν ὑπὲρ γυναικῶν ἐπενοήθησαν, ἀσμένως τὴν ἀφορμὴν ἥρπακα· μόνος γὰρ ὁ ἄρρην ἔρως κοινὸν ἡδονῆς καὶ ἀρετῆς ἐστιν ἔργον. εὐξαίμην γάρ, εἴπερ ἦν ἐν δυνατῷ, τὴν ἐπήκοόν ποτε τῶν Σωκρατικῶν λόγων πλατάνιστον, Ἀκαδημίας καὶ Λυκείου δένδρον εὐτυχέστερον, ἐγγὺς ἡμῶν ἑστάναι πεφυκυῖαν, ἔνθ᾿ ἡ Φαίδρου προσανάκλισις ἦν, ὥσπερ ὁ ἱερὸς εἶπεν ἀνὴρ πλείστων ἁψάμενος χαρίτων· αὐτὴ τάχα ἂν ὥσπερ ἡ ἐν Δωδώνῃ φηγὸς ἐκ τῶν ὀροδάμνων ἱερὰν ἀπορρήξασα φωνὴν τοὺς παιδικοὺς εὐφήμησεν ἔρωτας ἔτι τοῦ καλοῦ μεμνημένη Φαίδρου. πλὴν ἐπεὶ τοῦτ᾿ ἀμήχανον, ἦ γὰρ πολλὰ μεταξὺ ξένοι τε ἐπ᾿ ἀλλοτρίας γῆς ἀπειλήμμεθα καὶ πλεονέκτημα Χαρικλέους ἐστὶν ἡ Κνίδος, ὅμως τἀληθὲς οὐ προδώσομεν νικηθέντες ὄκνῳ. [32] μόνον ἡμῖν σύ, δαῖμον οὐράνιε, καιρίως παράστηθι φιλίας εὐγνώμων, ἱεροφάντα μυστηρίων Ἔρως, οὐ κακὸν νήπιον ὁποῖον ζωγράφων παίζουσι χεῖρες, ἀλλ᾿ ὃν ἡ πρωτοσπόρος ἐγέννησεν ἀρχὴ τέλειον εὐθὺ τεχθέντα· σὺ γὰρ ἐξ ἀφανοῦς καὶ κεχυμένης ἀμορφίας τὸ πᾶν ἐμόρφωσας. ὥσπερ οὖν ὅλου κόσμου τάφον τινὰ κοινὸν ἀφελὼν τὸ περικείμενον χάος ἐκεῖνο μὲν ἐς ἐσχάτους Ταρτάρου μυχοὺς ἐφυγάδευσας, ἔνθα ὡς ἀληθῶς σιδήρειαί τε πύλαι καὶ χάλκεος οὐδός, ὅπως ὑπ᾿ ἀρρήκτου δεθὲν φρουρᾶς τῆς ἔμπαλιν ὁδοῦ εἴργηται· λαμπρῷ δὲ φωτὶ τὴν ἀμαυρὰν νύκτα πετάσας παντὸς ἀψύχου τε καὶ ψυχὴν ἔχοντος ἐγένου δημιουργός· ἐξαίρετον δὲ ἐγκεράσας ὁμόνοιαν ἀνθρώποις τὰ σεμνὰ φιλίας πάθη συνῆψας, ἵν᾿ ἐξ ἀκάκου καὶ ἁπαλῆς ἔτι ψυχῆς ἡ εὔνοια συνεκτρεφομένη πρὸς τὸ τέλειον ἀνδρῶται. [33] γάμοι μὲν γὰρ διαδοχῆς ἀναγκαίας εὕρηνται φάρμακα, μόνος δὲ ὁ ἄρρην ἔρως φιλοσόφου καλόν ἐστι ψυχῆς ἐπίταγμα. πᾶσι δὲ τοῖς ἐκ τοῦ περιόντος εἰς εὐπρέπειαν ἠσκημένοις ἕπεται τιμὴ πλείων ἢ ὅσα τῆς παραυτὰ χρείας ἐπιδεῖται, καὶ πάντῃ τοῦ ἀναγκαίου τὸ καλὸν κρεῖττον. ἄχρι μὲν οὖν ἀμαθὴς ὁ βίος ἦν οὐδέπω τῆς καθ᾿ ἡμέραν πείρας πρὸς τὸ βέλτιον εὐσχολῶν, ἀγαπητῶς ἐπ᾿ αὐτὰ τὰ ἀναγκαῖα συνεστέλλετο, τῆς δὲ ἀγαθῆς διαίτης ἐπείγων ὁ χρόνος οὐ παρέσχεν εὕρεσιν. ἐπειδὴ δὲ αἱ μὲν ἐσπευσμέναι χρεῖαι πέρας εἶχον, οἱ δὲ τῶν ἐπιγιγνομένων ἀεὶ λογισμοὶ τῆς ἀνάγκης ἀφεθέντες ηὐκαίρουν ἐπινοεῖν τι τῶν κρειττόνων, ἐκ τούτου κατ᾿ ὀλιγον ἐπιστῆμαι συνηύξοντο. τοῦτο δ᾿ ἡμῖν ἀπὸ τῶν ἐντελεστέρων τεχνῶν ἔνεστιν εἰκάζειν. αὐτίκα πρῶτοί τινες ἄνθρωποι γενόμενοι τοῦ καθ᾿ ἡμέραν λιμοῦ φάρμακον ἐξήτουν, εἶθ᾿ ἁλισκόμενοι τῇ πρὸς τὸ παρὸν ἐνδείᾳ, τῆς ἀπορίας οὐκ ἐώσης ἑλέσθαι τὸ βέλτιον, τὴν εἰκαίαν πόαν ἐσιτοῦντο καὶ μαλθακὰς ῥίζας ὀρύττοντες καὶ τὰ πλεῖστα δρυὸς καρπὸν ἐσθίοντες. ἀλλ᾿ ἡ μὲν ἀλόγοις ζῴοις μετὰ χρόνον ἐρρίφη, σπόρον δὲ πυροῦ καὶ κριθῆς εἶδον αἱ γεωργῶν ἐπιμέλειαι εὑροῦσαι κατ᾿ ἔτος ἐκνεάζοντα. καὶ οὐδὲ μανεὶς ἂν εἴποι τις ὅτι δρῦς στάχυος ἀμείνων. |

|

[34] Moreover, did not men right from the start of human life, because they needed protection from the elements, skin wild beasts and clothe themselves in their woolly coats? And as refuges against the cold they thought of mountain caves or the dry hollows afforded by old roots or trees. Then, ever improving the imitative skill that started thus, they wove themselves cloaks of wool and built themselves houses, and imperceptibly the crafts that concentrated on these things, being taught by time, replaced simple fabrics with ornate garments of greater beauty, and instead of cheap cottages they devised lofty mansions of expensive marble, and painted the native ugliness of their walls with the luxuriant dyes of colour. However each of these crafts and accomplishments has, after being mute and plunged in deep forgetfulness, gradually risen, as it were, to its own bright zenith after long being set. For each man made some discovery to hand on to his successor. Then each successive recipient, by adding to what he had already learnt, made good any deficiencies. [35] Let no one expect love of males in early times. For intercourse with women was necessary so that our race might not utterly perish for lack of seed. But the manifold branches of wisdom and men’s desire for this virtue that loves beauty were only with difficulty to be brought to light by time which leaves nothing unexplored, so that divine philosophy and with it love of boys might come to maturity. Do not then, Charikles, again censure this discovery as worthless because it wasn’t made earlier, nor, because intercourse with women can be credited with greater antiquity than love of boys, must you think love of boys inferior. No, we must consider the pursuits that are old to be necessary, but assess as superior the later additions invented by human life when it had leisure for thought. [36] For I came very close to laughing just now when Charikles was praising irrational beasts and the lonely life of Scythians.[36] Indeed his excessive enthusiasm for the argument almost made him regret his Greek birth. For he did not hide his words in restrained tones like a man contradicting the thesis that he maintained, but with raised voice from the full depth of his throat says, “Lions, bears, boars do not love others of their own sort but are ruled by their urge only for the female.” And what’s surprising in that? For the things which one would rightly choose as a result of thought, it is not possible for those that cannot reason to have because of their lack of intellect. For, if Prometheus or else some god had endowed each animal with a human mind, they would not be satisfied with a lonely life among the mountains, nor would they find their food in each other, but just like us they would have built themselves temples and, though each making his hearth the centre of his private life, they would live as fellow-citizens governed by common laws. Is it any wonder that, since animals have been condemned by nature not to receive from the bounty of Providence any of the gifts afforded by intellect, they have with all else also been deprived of desire for males? Lions do not have such a love, because they are not philosophers either. Bears have no such love, because they are ignorant of the beauty that comes from friendship. But for men wisdom coupled with knowledge has after frequent experiments chosen what is best, and has formed the opinion that love between males is the most stable of loves. [37] Do not, therefore, Charikles, heap together courtesans’ tales of wanton living and insult our dignity with unvarnished language nor count Heavenly Love as an infant, but learn better about such things though it’s late in your life, and now at any rate, since you’ve never done so before, reflect in spite of all that Love is a twofold god who does not walk in but a single track or exert but a single influence to excite our souls; but the one love, because, I imagine, his mentality is completely childish, and no reason can guide his thoughts, musters with great force in the souls of the foolish and concerns himself mainly with yearnings for women. This love is the companion of the violence that lasts but a day and he leads men with unreasoning precipitation to their desires. But the other Love is the ancestor of the Ogygian age,[37] a sight venerable to behold and hedged around with sanctity, and is a dispenser of temperate passions who sends his kindly breath into the minds of all. If we find this god propitious to us, we meet with a welcome pleasure which is blended with virtue. For in truth, as the tragic poet says, Love blows in two different ways, and the one name is shared by differing passions. For Shame too is a twofold goddess, with both a beneficial and a harmful role. Shame which to men doth mighty harm and It need not surprise us, therefore, that passion has come to have the same name as virtue so that both unrestrained lust and sober affection are called Love. [38] Charikles may ask if I therefore think marriage worthless and banish women from this life, and if so, how we humans are to survive. Indeed, as the wise Euripides[39] says, it would be greatly to be desired if we had no intercourse with women but, in order to provide ourselves with heirs, we went to shrines and temples and bought children for gold and silver. For we are constrained by necessity that puts a heavy yoke on our shoulders and bids us obey her. Though therefore we should by use of reason choose what is beautiful, let our need yield to necessity. Let women be ciphers and be retained merely for child-bearing; but in all else away with them, and may I be rid of them. For what man of sense could endure from dawn onwards women who beautify themselves with artificial devices, women whose true form is unshapely, but who have extraneous adornments to beguile the unsightliness of nature? [39] If at any rate one were to see women when they rise in the morning from last night’s bed, one would think a woman uglier than those beasts[40] whose name it is inauspicious to mention early in the day. That’s why they closet themselves carefully at home and let no man see them. They’re surrounded by old women and a throng of maids as ugly as themselves who doctor their ill-favoured faces with an assortment of medicaments. For they do not wash off the torpor of sleep with pure clean water and apply themselves to some serious task. Instead numerous concoctions of scented powders are used to brighten up their unattractive complexions, and, as though in a public procession, each maid is entrusted with something different, with silver basins, ewers, mirrors, an array of boxes reminiscent of a chemist’s shop, and jars full of many a mischief, in which she marshals dentifrices and contrivances for blackening the eyelids. |