EDMUND MARLOWE’S ALEXANDER’S CHOICE REVIEWED BY C. CAUNTER

Alexander’s Choice, a love story set at England’s most famous boarding school, Eton College, and written by old boy Edmund Marlowe, was published in 2012. This review, including the cited page numbers, refers to the slightly amended edition of 2022.

WARNING: This review contains spoilers and is intended as post-discussion for the benefit of readers of the novel. To prospective readers: this novel is likely to prove very much worth your while, providing ample food for thought even if one were to disagree with (parts of) its message.

A novel at war with the spirit of its age

January 2023

Edmund Marlowe’s Alexander’s Choice is a unique novel. There are other novels about boy-man-love, including ones that take a positive view, but I had never yet come across one that, ingeniously wrought in the form of a compelling story, makes such a complete, informed case for this love, contrasting two societies – classical Greece and the modern West – that have diametrically opposed takes on it. The present work is especially unique in regard of the immensely erudite apologia it delivers in novel format of Greek love as a very specific, beneficial social institution with historical antecedents, completely unrelated to the modern gay identity. Even readers who come away sceptical about the idealised tones with which Greek love is here presented cannot but understand that something is monstrously wrong with our supposedly progressive and enlightened society’s extreme, and escalating, response to it.

The juxtaposition of the ancient world and the modern one is cleverly achieved by letting the former weigh in on the latter insistently: through student Alexander Aylmer’s passion for ancient history, through the study of the classics undertaken at Eton, and through Mary Renault’s novels about Alexander the Great being discovered simultaneously by Aylmer and by his English teacher Damian Cavendish. Their mutual discovery of Greek love as a closely defined institution even begins to influence Damian at a point where he has come to terms with his love for Alexander, but still believes there is no sexual element to their mutual attraction: ‘If he did love Alexander, then presumably it must be love of the soul, and some would say that was the noblest love of all. In that case, could he not let himself go emotionally and give him all the benefits of Greek love, safe in the knowledge that his sexual feelings were chastely English?’ (p. 203).

The novel lets the reader feast on a succession of dramatic twists that never lets up: one is propelled forward throughout, and the narrative nowhere slackens. Part of what makes it compulsive reading is not just the unrelenting dramatic action, but the agonising, the manoeuvring and the second-guessing to which various characters give themselves over as they attempt to decide on the correct or most advantageous course of action, and as they journey in quest of the elusive fulfilment of their wishes and needs. As a result, the reader is kept on tenterhooks while it remains undecided whether the characters will finally end up getting what they long for.

Most characters, especially the main ones, are quite nuanced, their doubts and evolving views set out painstakingly. A fine example is Julian Smith’s father, who is good-natured and broad-minded and yet ends up convincing himself, and consequently his son, that the best way to proceed would be for Julian to betray his friendship with Alexander. It’s also quite clever for the author to have made Julian’s dad a German-Jewish Holocaust survivor who initially sees Britain as the tolerant antithesis of the nightmarish regime he has just barely escaped with his life from. As Britain’s punitive machinery is set in motion on the discovery of Alexander’s love affair, the novel thus draws a parallel of nightmarish, dehumanising systems that, even if using the Nazi atrocities as a warning is a more than well-trodden path, is valid and crystal-clear. Those lesser characters who are less than nuanced, such as inspector Hatchet, do not detract from the realism because they are still accurate, lacking all nuance and sophistication in real life as they do.

Of Peter Leigh, a boarder of low moral fibre who himself has experienced crushes on some of his schoolmates, it is said on page 110: ‘His own traumatic experience of last Half had reinforced his belief that the only way to get along in life was to make oneself as agreeable as possible to the acceptable arbiters of decent, sociable behaviour.’ Peter thus represents one end of a spectrum: those who suppress their own nature and conform to the prevailing morals and beliefs – no matter whether these are right or wrong. Julian is further along the spectrum and struggles actively to come to terms with his feelings and not to allow society to stifle their expression, although he ultimately fails. (I did jot down, having come to page 172: ‘I can't believe Julian could bring himself to go along with the pressure exerted to end his friendship with Alexander.’) Damian is on the other end of the spectrum, able through self-education to see beyond society’s prevailing myths and fallacies, and following his feelings, whether bravely or naively, in spite of the extreme risk he runs.

My main reservation in terms of believable character behaviour, aside from Julian’s U-turn just when he suspects that what he most craves is within imminent reach, concerns the amount of risk Damian chooses to run unnecessarily. It is puzzling how comparatively little such a perceptive and intelligent person as Damian worries about the need for discretion and caution given the grave consequences the consummation of his and Alexander’s love is certain to have if discovered. He blithely allows Alexander to spend every minute of his spare time in his teacher’s flat in the Eton High Street. This strange carelessness is accounted for to an extent by the circumstance that before meeting Alexander he was entirely unaware of any attraction to boys on his part (and thus he never paid attention to the phenomenon and the ramifications of its indulgence), by the fact that mad love spurs both himself and Alexander on in their tryst, by the fact that the novel is set in 1984; that is, still in the early, ‘naive’ days of the victimological era of extreme persecution, and by an observation made by Damian’s father: ‘being so giving himself, Damian had never had much idea of the malice of others’ (p. 209). Indeed, once his love affair is detected, Damian expects his promising teaching career to be over but is astounded when the police turn up at his flat to take him away.

The process by which Damian, initially without realising it, falls in love with Alexander is described impressively, making it clear how the process of falling in love begins in the subconscious and, after a time of sly incubation, bursts forth into our conscious awareness with bewildering and overwhelming suddenness: ‘He had to force himself to do his work, but when in the evening it was finished, a gloom settled on him which he could only alleviate by thinking of Alexander’s return on the morrow. It was this that finally made Damian realise he loved the boy to the depths of his soul. To try to pass his feelings off as mere fondness was ridiculous’ (p. 210).

Although the reader knows or at least suspects from the outset that a terrible drama is impending, the story avoids being predictable by introducing first fellow schoolboy Julian as Alexander’s special friend, and only then teacher Damian. One agonises along with Julian as he pursues bliss and gets tantalisingly far, but ultimately lets the pressure exerted on him by authority figures goad him into abandoning his dream and becoming a Judas. No sooner does this story line approach its climax than the suspenseful story of Alexander and Damian growing closer and closer to each other gets underway. At one point I thought it was Julian who, the enormity and irreversibility of his abandonment of Alexander having sunk in, might end up killing himself (and who knows, he may meet that fate some time after the novel ends). On page 317 his descent into despondency, and his awareness of it, is described impressively: ‘He sat in the armchair in his room in silent darkness, as if the light might expose the rottenness of his soul.’

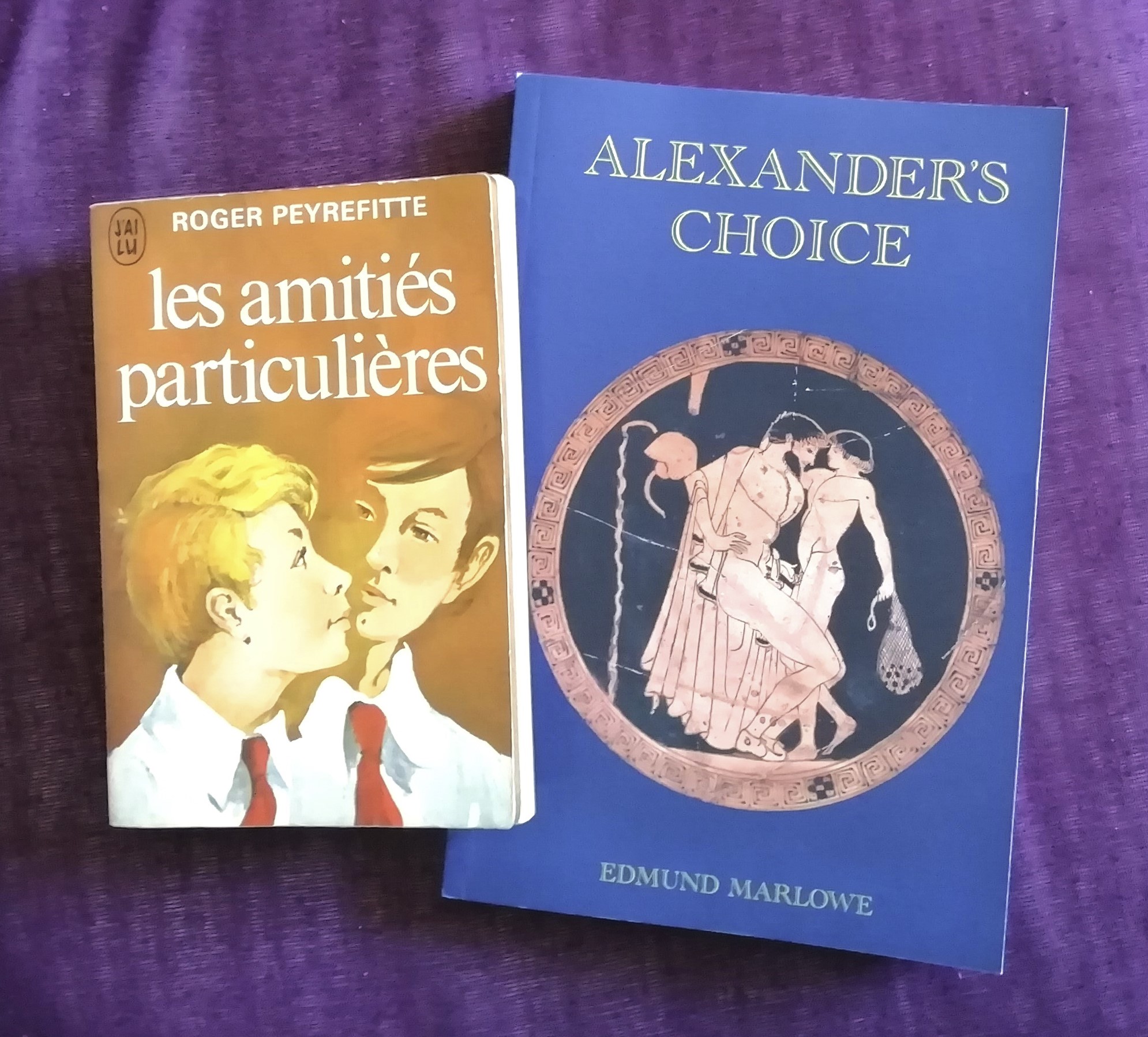

In the end, however, it is Alexander’s suicide that is described with breathtaking realism. As early as page 12 there is a foreshadowing of a clash between Alexander’s wilful, principled nature and society’s implacable rules: ‘it looked as though he would defy as far as he thought practicable any rule he thought unreasonable.’ His ultimate fate is in a way an homage to Roger Peyrefitte’s famous special-friendships novel Les amitiés particulières (1943): Alexander, having exercised and fruitlessly defended his freedom of choice in matters of friendship and love, makes a final choice which mirrors the final choice made by Alexandre Motier in Les amitiés particulières. As a review by Cuthbert points out, however, Peyrefitte’s Alexandre makes his fateful decision because of a misunderstanding, whereas Marlowe’s Alexander makes his decision once he understands what society is really like. The only consequence the latter is too devastated to foresee is that, as a final act of desecration, his real murderers will pin the blame for his death on his lover.

Julian being presented as Alexander’s suitor before Damian comes into clear relief (puns intended) not only avoids predictability, but heightens the foreboding: first we see a looming drama about an older schoolboy’s love affair with a younger boy; then, to our astonishment, there rises up from behind it the story of a teacher’s love affair with a schoolboy, and we realise that the stakes have just become magnitudes greater. It was not until I had crossed the novel’s halfway mark that it sank in that Julian might end up being the jealous instrument of Alexander’s and Damian’s downfall.

Even if Alexander and Damian eventually take over as the story’s star-crossed lovers, a lot of its thrust is developed while the spotlight is still on Julian. There is much food for thought in his unspeakably melancholy realisation that he was born at the wrong time. This realisation is made salient by his discovery of Eton’s House Books from only two decades before his time, in which many an openly professed crush between older and younger schoolboys is attested to; a culture that had vanished by the 1980s. This is just one of the ways in which Edmund Marlowe’s insider knowledge of Eton is worked to great effect into the weft of the story, lending it an inimitable couleur locale. The following point is memorably made to characterise the contemporary society Julian comes to feel it is his misfortune to have been born into: ‘nowadays, safety is everything, and happiness and freedom must always give way to it’ (p. 267).

While he doesn't undergo a personal tragedy of the magnitude of Julian’s, Walter Cavendish (Damian’s father) is similarly shown to be disenchanted with his own time, in Walter’s case on discovering the illiberalism of many of the leftist comrades with whom he had gone to fight in the Spanish Civil War: ‘His disillusionment thereafter encompassed the entire drift of modern politics and society and he realised he was one of those unhappy men at war with the spirit of their age’ (p. 204). The novel is essentially about people finding themselves, willy-nilly, at war with the spirit of their age, and about the question whether, given this conflict, they will choose to exercise their freedom nonetheless – one of the choices faced by Alexander as well as by Julian and Damian – or to surrender it by way of a peace offering to society. (In parallel, housemaster Mr. Hodgson and headmaster Mr. Allenby face choices as they, too, come to realise just how counterproductively extreme society’s response to underage and age-discrepant love has become.)

One aspect of the said spirit of the age is formulated arrestingly on page 409:‘a world in which all moral questions were being answered with final certainty thanks to progress.’ This ‘brave new world’ of concerned members of society, news outlets growing fat on fanning the flames of persecution, activist social workers, the mandatory involvement of the police, mountain-out-of-molehill mandatory sentencing, and other ever-escalating solutions to neutralise predators is consummately raked over the coals in the final stages of the novel. No less consummate, and informed, is the evocation of a very different world that met its demise only in the recent past: the public schools where Greek love affairs were allowed to flourish, or turned a blind eye to, before new sexual identities and external political pressures put a virtual end to this centuries-old arrangement.

Alexander’s Choice is not, however, just a tragic, bitter tale of individuals being crushed by society; it’s not just ‘a novel to slit your wrists to’. Ample space is devoted to the evolving thoughts, beliefs, needs, wishes, curiosities, follies, griefs, hopes and desires of characters such as Alexander, Julian and Damian, but also of such characters as Alexander’s newly widowed father and Julian’s father, who wants above all for his only son to get the top education that was never available to himself. In setting out all of these inner lives, the novel is interested in exploring which other characters can bring fulfilment to a given person and which, by contrast, threaten to frustrate the sought fulfilment. Julian, himself a bit of an ugly duckling, jumps at the opportunity to show his chivalrous side, is elated by the experience of friendship with someone as sensitive and attractive as Alexander and is dying to know what it would be like to have sex with him.

Alexander is the character whose inner life is described in greatest detail, and is arguably the most tormented, having to cope with his mother’s sudden death and having a sensitive, trusting nature that sets him up for disappointment. He craves someone who will love him and whom he can rely on to be there for him. In addition to this, he is frustrated because his desire for sex with a girl remains unfulfilled. Initially, the person supplying his emotional need is Julian; afterwards it’s Damian. Damian, for his part, is a born giver of love, protection and knowledge. He feels fulfilled when he can lavish his instinct to nurture on Alexander; the latter in turn comes to life under Damian’s attention. The way these different emotions and needs play out in the passionate love relationship that quickly develops between the two, the way sex is not the object or the starting point but is discovered by both as a natural vehicle for their devotion to one another, and the way both partners are transformed by the mystical workings of love and desire, is developed in great detail and with great care. In this novel, individuals fall deep in their despair and loneliness, but are also lifted up high through the help, altruism and kindness of others (another example is the non-sexual friendship of Julian’s father Alfred with Captain Holland, his English liberator when as a teenager Alfred was imprisoned in Bergen-Belsen concentration camp).

As far as the philosophical points developed in the novel – not necessarily the author’s points of view, but still setting a tone – I found myself raising an eyebrow at the following reflection by Damian (p. 188): ‘Much as they [gay students at Cambridge] had tried hard to give an impression of having a good time, he had felt sure that a tinge of sadness underlay their gaiety and he suspected that its ultimate pointlessness was the cause.’ The alleged sad, depressing and dead-end nature of the homosexual lifestyle is a well-worn trope employed by those who oppose homosexuality across the board, regardless of the ages involved; I was sad to see it invoked by Damian.

Another reservation that suggested itself to me is that, with the novel’s emphasis on explaining Greek love as a highly specific, time-honoured social mechanism often indulged in by men and boys who are precisely not principally homosexual (let alone ‘gay’), some readers may come away with a reinforced impression that Greek love relationships are, at best, highly transient and that the boy, on sprouting hair in unacceptable places, will be predictably left in the lurch. The novel goes to some length explaining why the transient nature of such relationships is a feature, not a bug (it allows the boy, having been nurtured at a time of need, to move on to – usually – heterosexual life, and the sexual relationship often morphs into lifelong friendship), but it does not address the sheer variety of human relational and sexual expressions out there: just like not all homosexual and bisexual persons fit in with the contemporary ideal of the androphile gay and his jealously defended wedding cake, not all boy lovers stop being sexually attracted to boys when the latter reach a certain cut-off point.

The novel being highly didactic might be experienced by some readers as a drawback, and some will argue that the characters – chiefly Alexander – only act the way they do in service of the crusading author’s agenda (one review calls all characters different ‘avatars’ of Marlowe). In the interest of its didactic quest, the story presents a number of exemplary outcomes, which can be categorised as either the most utopian or the most dystopian of a range of possible outcomes: Alexander is flawlessly beautiful and extremely noble; Damian is maximally attractive and selflessly caring; both are impassioned by the classical world and enlightened by compelling descriptions of the practice of Greek love; they experience the most ideal connection of souls and bodies imaginable; Alexander gets physically assaulted and abused by the police; he takes his own life in response to the outside intervention in his happiness and his needs; Damian gets killed in prison for being seen as so much worse than any other class of criminal. All taken together, these exemplary outcomes could be seen as painting an unrealistic picture and as only being marshalled by the author in the interest of presenting the ultimate apologia of Greek love and indictment of our 1984-style – with regard to this subject – society.

But there is a difference between the limited likelihood of all of these outcomes converging in a real-world case the way they do in the novel and the argument, if anyone wanted to make it, that any one of these outcomes could not and does not happen in the real world. The extent to which some of the outcomes, such as the younger lover’s suicide, have actually been known to occur would be interesting to explore. More importantly, however, the reality that sexual relationships such as that between Alexander and Damian do actually occur – relationships experienced as pleasurable and beneficial by both parties during as well as long after the event, and this in the face of extreme antagonism from society – is evidenced by countless testimonies on the part of (former) adolescent lovers of adult men and women.[1] In the face of this reality, Alexander and Damian’s ideal relationship cannot be dismissed, as some reviewers do, as feverish wishful thinking on the part of a dirty-minded, middle-aged writer whose understanding of the real world is warped by his perverse fantasies.

Alexander’s Choice does not pull punches, unflinchingly delving into the single-most controversial issue in contemporary society. I was from the early stages of reading it, and have remained, extremely impressed and moved by it. I find it, I’ll say it again, a novel not quite like any other I’ve ever come across. It does not just describe a tragedy – as well as great beauty and the fulfilment of love, however briefly – but lays out the nature of that tragedy, how it came about, how things were once different, and how things might be different again if it weren’t for the fact that individuals and human societies are impervious to reason and incapable of compassion when our ritualistic, expiatory need for sacrificing scapegoats is at stake. Alexander’s Choice is magnificent and unforgettable.

[1] See e.g. Theo Sandfort, Boys on Their Contacts with Men: A Study of Sexually Expressed Friendships, 1987, and T. Rivas, Positive Memories, 2013 (3rd, enlarged edition 2016).

Comments

If you would like to leave a comment on this webpage, please e-mail it to greek.love.tta@gmail.com, mentioning either the title or the url of the page so that the editor can add it.